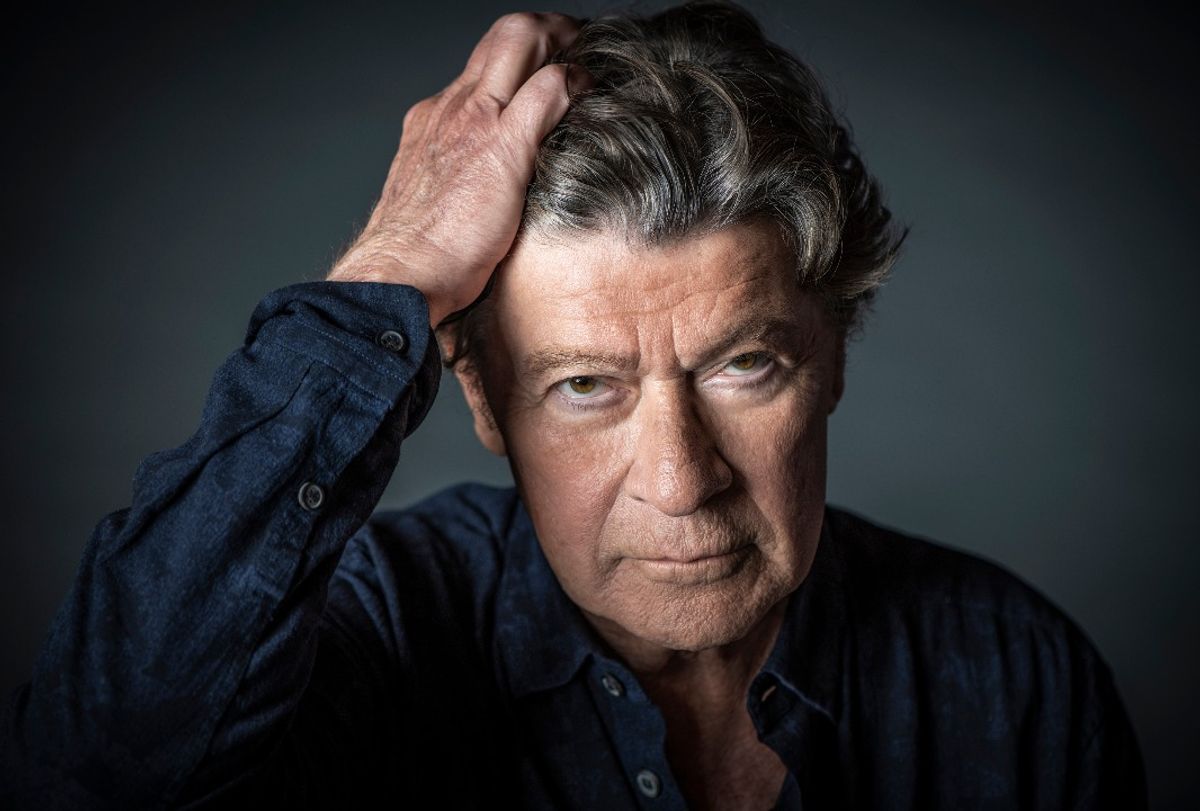

Robbie Robertson, erstwhile member of The Band, recounted his musical experiences with the legendary group in his 2016 memoir, "Testimony." That book forms the basis of "Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band," director Daniel Roher's poignant, music-filled documentary that is currently available on demand and out on DVD/Blu-Ray May 26.

The film, produced by Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, and Brian Grazer, is a reflection on the lightning in a bottle that has been Robertson's career. The musician is a terrific raconteur, describing personal stories of being on a Canadian reservation, meeting the Jewish uncles he didn't know he had, and discovering rock 'n' roll. The bulk of the film is focused on his career as performer, which began when he started writing songs for and playing with Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks. Eventually he started touring with Bob Dylan — to booing crowds that didn't appreciate a "new style of playing" — then formed The Band with Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson. (The last, who is still alive, is not interviewed in the film, perhaps deliberately because of past songwriting disputes.) Their debut album, "Music from Big Pink," was magical, and generated a handful of subsequent albums before they filmed "The Last Waltz," Martin Scorsese's concert documentary that recorded their final public appearance.

"Once Were Brothers" chronicles The Band's success and its tragedies — car accidents and addictions — all of which made "something so beautiful go up in flames," as Robertson eloquently describes it.

The musician chatted with Salon about his life, music, hypnosis, and his new film.

You have some wonderful descriptions of music — that the music of the Delta region is "as heavy as the air." Or the way Dylan's electric guitar was "a musical revolution that expanded horizons." I'm curious what is it about a song that impresses you? How does your ear attune?

There are a hundred different things that can push the button, and sometimes it's the story being told and purely that. And sometimes it's what I learned from Bob Dylan — that someone may be saying something that is fun to hear, or they have a cool way of putting it, but it is something that needs to be said. Early on for Bob, that was the path that he was following. I came in on a different train. A lot of people who got into rock and roll came through a folk music path. I didn't at all. For me, rock 'n' roll was the noise that shook the world for me. It had to do with a sound and a rhythm, a rebellion, an attitude, and number one — it was sexy. So, for me, when I was 13 years old, rock 'n' roll certainly rang my bell.

In the meantime, before that, I was in this very unusual setting. My mother was born and raised on the Six Nations Indian reserve. A lot of the Indians played instruments, and that's what got me to play music. They sang country music. That was their connection with the outside world because they lived in the country. It was connected to cowboys. So, it was an irony to see Indians singing cowboy songs. I made this joke before, too. My first guitar that my parents got me, out of a catalog, had a picture of a cowboy on it because that's the way they came. Indians taught me how to play it.

You talk early in the film about the creative process is best when you are "caught off guard." Thinking about your songwriting, you discuss the freedom to write without constraints. The film illustrates how you came up with the line, "I pulled into Nazareth . . ." for "The Weight." Do you write lyrics and set them to music, or is there a beat in your head when you compose the lyrics?

I couldn't imagine at a very young age that there was a place for songwriters to go and do this somewhere. I don't know where it came from. It was such a beautiful mystery. When I was 15 years old, Ronnie Hawkins took me from Toronto to New York to the Brill Building so I could hear songs that would be good for him to record. He had faith in my ear. I went and saw a songwriting factory. [Jerry] Leiber and [Mike] Stoler, were there, and Otis Blackwell was in another room. They wrote big, big hit songs for people who went out to the world. I went, "Whoa! That's Tin Pan Alley. This is a mythical place." I thought, "Isn't that fantastic?"

So, writing a song for these guys is like getting up and going to work. There were a lot of songwriting teams. But they would go into this room sit down, and whether you bring anything with you or not is the question. Sometimes you can think of a phrase, "lonely weekends," and I'm going to write a song about lonely weekends. But 90% of the time I'd pick up a guitar or sit at a piano and not know what was going to happen. But the feeling of putting your hands on the keys and make a sound that implies something that helps you tell a story, or find a phrase, and they come together. Sometimes you find a beautiful chord progression and you think I have to write lyrics to that. Dylan wrote all the words, and I thought: Doesn't the music come first? That's traditionally how [George] Gershwin or [Burt] Bacharach would work. They had a formula: write the words, or write the music. I didn't have a formula, I was just looking for that ray of light to happen, and a lot of times I'd sit down with a guitar and nothing happened. I'm bored. Or, I don't like this guitar. And another time it was taking me somewhere. I found a clue and that led to another. A lot of people have their own secret method and my secret method was show up with a blank canvass.

There are some very dark moments in the film about your bandmates' addictions to drugs and alcohol. You reflect on this in the film. What can you say about those experiences?

Being in the moment at the time, it was, on a good day, frightening to think, "I hope somebody doesn't die." That's an awful feeling. Then you think we're here for a reason. I hope we can do what we came here to do: to play music. This is when it escalated to a place — it's a progressive thing. When it got to that level, it was a throw of the dice. Let me be very clear: I was no angel. I was not Mr. Responsible. I was just better off than others, and in a position to say, "Is everyone OK?" But even if people aren't OK, they say they are.

It got to a place where I thought someone is going to die. It was being out there on the road — a wilderness in itself. In this period of the 1970s, everywhere you went people wanted to befriend you by having some kind of drug to offer. "I got a present for you . . ." It was always a magnet pulling you somewhere, and that's why "The Last Waltz" appealed to me. We had to get out of the way and not be so vulnerable. We didn't know anything about addiction. The Band was in no way unique in this area. Every group was in the same boat.

You visit Levon Helm on his deathbed. I understand from the film that there was conflict over songwriting credits and money. Do you care to comment further about waiting until it was too late to reconnect with Helm?

Here's something that I've not said before. To this day, on The Band's songs, I share the publishing and songwriting credit with Levon. The other guys said they wanted to sell their part of the publishing. When we started out, everyone was supposed to write songs. [When they didn't] I thought they were being lazy. But some people can write songs, and some can't. Levon didn't write songs. I gave him credit on some songs because he was around. Garth was a great musician, but he couldn't write. Ringo Starr doesn't write songs. Charlie Watts doesn't write songs, and they don't share publishing credit with the other guys in their groups. After 16 years together, Levon never once mentioned songwriting. When it came up, I was generous about it. I did stuff I didn't have to do, and I did it to be a good friend. It was 10 or 15 years after that when Levon was struggling financially, and he's blamed someone else for what happened with him. This was another case of that.

I was also struck by the suggestion in the film that David Geffen signed and courted you because he really wanted Dylan. What are your thoughts on that?

No. I know that's been said, but David is still one of my best friends. We hit it off. He [said] he could get us off Capitol Records and let us do whatever we wanted. He tried to make it better than what we had and encouraged me to move out west. I had done the Woodstock thing. In that process, I said you should meet Bob who moved out to Malibu. It was my idea. David never asked me to introduce him to Bob. David said we should do another tour together. That would be history! Bob and I thought that would be fun. Bob hadn't been on the road in eight years. He was yearning to do something.

"The Last Waltz" is such a canonical documentary, and it helped cement your working relationship with Martin Scorsese. Can you talk about your collaboration with him over the years?

I've worked on 10 or more movies with him and it's been such a broad horizon of things that needed to be done and figured out. We're even working on the music for the next movie. It's a remarkable, wonderful relationship. Marty has a very special gift not only for filmmaking, but his sensibility in music as well. What we have done has cemented itself over the years. He's a dear friend. I love working with him.

The film doesn't touch on your acting career, but why didn't you pursue that further after appearing in "Carny"?

I did so much on that movie, I burned out a little bit. The thing about music that is gratifying is the solitary part of it. You go off into your own world, do something, and you come back out with something that didn't exist. Of course, you collaborate with others, but that experience in film, there are so many cooks in a kitchen! I produced "The Last Waltz" and "Carny." The director and writer and producer of "Carny" talked me into being in it. It was incredible, but after that, I thought, hand me that guitar please!

You state in the film that you are left with memories. What comes to mind when you think about on those heady days? Do you look back with fondness or regret?

It was like everything else — half of it was beautiful and half of it, I didn't know what the f*** was going on. It's a balancing act. God, there were good intentions. John Lennon really wanted people to connect in the most beautiful way. Who doesn't want peace? Or that love is special and the most important thing in the world? To look back and think, "That's a waste" is awful. People really meant well.

What do you think about the current music industry versus back in the day? Things have changed drastically, but do you think it has improved over time?

I think there is always great music being made, and people doing really special stuff. Sometimes you have to dig deeper or look past the obvious. To me the difference is the late 1960s and 1970s — that period everyone holds holy — is because the music was the voice of the generation. Now it's just great entertainment. Some people are really talented. But people listened to music [back then] to know how they connected. Now unity is an absurdity.

I was amused by the story about having a hypnotist help you be able to perform. Was that a one-time thing or did you pursue hypnosis?

Years ago, I went to a hypnotist because I didn't want to smoke cigarettes anymore. I've experimented over the years, but no one was as good as Pierre Clement. It was unexpected. I was so sick and pining to feel better. I went with it. "Please help me and allow me to feel better." I said "I'll go under your spell or over your spell. I'll do whatever you want me to do."

"Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band" releases on DVD and Blu-Ray on Tuesday, May 26.

Shares