To hear some experts tell it, science denial is mostly a contemporary phenomenon, with climate change deniers and vaccine skeptics at the vanguard. Yet the story of Galileo Galilei reveals just how far back denial's lineage stretches.

Years of astronomical sightings and calculations had convinced Galileo that the Earth, rather than sitting at the center of things, revolved around a larger body, the sun. But when he laid out his findings in widely shared texts, as astrophysicist Mario Livio writes in "Galileo and the Science Deniers," the ossified Catholic Church leadership — heavily invested in older Earth-centric theories — aimed its ire in his direction.

Rather than revise their own maps of reality to include his discoveries, clerics labeled him a heretic and banned his writings. He spent the last years of his life under house arrest, hemmed in by his own insistence on the expansiveness of the cosmos.

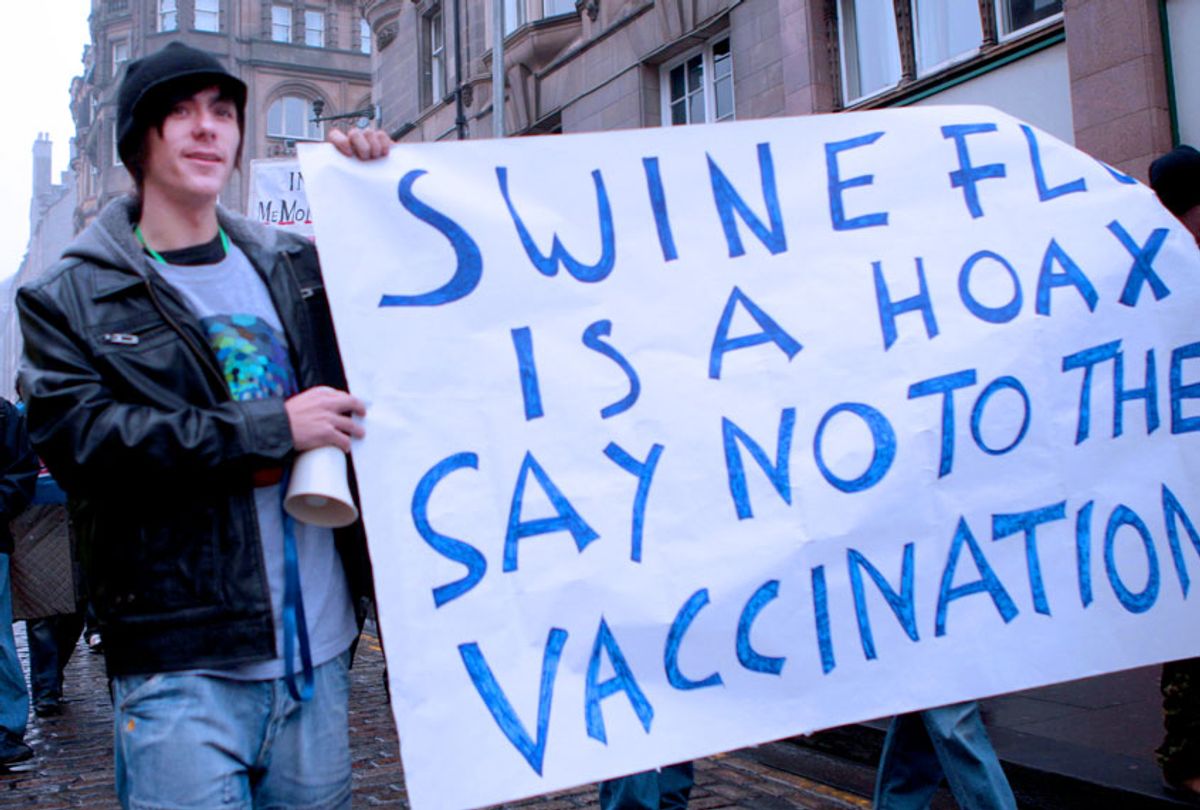

Nearly 400 years later, the legacy of denial remains intact in some respects. Scientists who publish research about climate change or the safety of genetically modified crops still encounter the same kind of pushback from deniers that Galileo did. Yet denialism has also sprouted some distinctly modern features: As Alan Levinovitz points out in "Natural: How Faith in Nature's Goodness Leads to Harmful Fads, Unjust Laws, and Flawed Science," sometimes we ourselves can become unwitting purveyors of denial, falling prey to flawed or false beliefs we may not realize we're holding.

Levinovitz passionately protests the common assumption that natural things are inherently better than unnatural ones. Not only do people automatically tend to conclude organic foods are healthier, many choose "natural" or "alternative" methods of cancer treatment over proven chemotherapy regimens. Medication-free childbirth, meanwhile, is now considered the gold standard in many societies, despite mixed evidence of its health benefits for mothers and babies.

"What someone calls 'natural' may be good," writes Levinovitz, a religion professor at James Madison University, "but the association is by no means necessary, or even likely." Weaving real-life examples with vivid retellings of ancient myths about nature's power, he demonstrates that our pro-natural bias is so pervasive that we often lose the ability to see it — or to admit the legitimacy of science that contradicts it.

From this perspective, science denial starts to look like a stunted outgrowth of what we typically consider common sense. In Galileo's time, people thought it perfectly sensible that the planet they inhabited was at the center of everything. Today, it might seem equally sensible that it's always better to choose natural products over artificial ones, or that a plant burger ingredient called "soy leghemoglobin" is suspect because it's genetically engineered and can't be sourced in the wild. Yet in these cases, what we think of as common sense turns out to be humbug.

In exploring the past and present of anti-science bias, Livio and Levinovitz show how deniers' basic toolbox has not changed much through the centuries. Practitioners marshal arguments that appeal to our tendency to think in dichotomies: wrong or right, saved or damned, pure or tainted. Food is either nourishing manna from the earth or processed, artificial junk. The Catholic Church touted its own supreme authority while casting Galileo as an unregenerate apostate.

In the realm of denialism, Levinovitz writes, "simplicity and homogeneity take precedence over diversity, complexity, and change. Righteous laws and rituals are universal. Disobedience is sacrilege."

The very language of pro-nature, anti-science arguments, Levinovitz argues, is structured to play up this us-versus-them credo. Monikers like Frankenfood — often used to describe genetically-modified (GM) crops — frame the entire GM food industry as monstrous, a deviation from the supposed order of things. And in some circles, he writes, the word "unnatural" has come to be almost a synonym for "moral deficiency." Not only is such black-and-white rhetoric seductive, it can give deniers the heady sense that they occupy the moral high ground.

Both pro-natural bias and the Church's crusade against Galileo reflect the human penchant to fit new information into an existing framework. Rather than scrapping or changing that framework, we try to jerry-rig it to make it function. Some of the jerry-rigging examples the authors describe are more toxic than others: Opting for so-called natural foods despite dubious science on their benefits, for instance, is less harmful than denying evidence of a human-caused climate crisis.

What's more, many people actually tend to cling harder to their beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence. Studies confirm that facts and reality aren't likely to sway most people's pre-existing views. This is as true now as it was at the close of the Renaissance, as shown by some extremists' stubborn denial that the Covid-19 virus is dangerous.

In one of his book's most compelling chapters, Livio takes us inside a panel of theologians that convened in 1616 to rule on whether the sun was at the center of things. None of Galileo's incisive arguments swayed their thinking one iota. "This proposition is foolish and absurd in philosophy," the theologians wrote, "and formally heretical, since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture." Cardinal Bellarmino warned Galileo that if he did not renounce his heliocentric views, he could be thrown into prison.

Galileo's discoveries threatened to topple a superstructure that the Church had spent hundreds of years buttressing. In making their case against him, his critics liked to cite a passage from Psalm 93: "The world also is established that it cannot be moved."

Galileo refused to cave. In his 1632 book, "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems," he did give the views of Pope Urban VIII an airing: He repeated Urban's statement that no human could ever hope to decode the workings of the universe. But Livio slyly points out that Galileo put these words in the mouth of a ridiculous character named Simplicio. It was a slight Urban would not forgive. "May God forgive Signor Galilei," he intoned, "for having meddled with these subjects."

At the close of his 1633 Inquisition trial, Galileo was forced to declare that he abandoned any belief that the Earth revolved around the sun. "I abjure, curse, and detest the above-mentioned errors and heresies." He swore that he would never again say "anything which might cause a similar suspicion about me." Yet as he left the courtroom, legend goes, he muttered to himself "E pur si muove" (And yet it moves).

In the face of science denial, Livio observes, people have taken up "And yet it moves" as a rallying cry: a reminder that no matter how strong our prejudices or presuppositions, the facts always remain the same. But in today's "post-truth era," as political theorist John Keane calls it, with little agreement on what defines a reliable source, even the idea of an inescapable what is seems to have receded from view.

Levinovitz's own evolution in writing "Natural" reveals how hard it can be to elevate facts above all, even for avowed anti-deniers. When he began his research, he picked off instances of pro-natural bias as if they were clay pigeons, confident in the rigor of his approach. "Confronted with a false faith, I had resolved that it was wholly evil," he reflects.

Yet he later concedes that a favoritism toward nature is logical in domains like sports, which celebrate the potential of the human body in its unaltered form. He also accepts one expert's point that it makes sense to buy organic if the pesticides used are less dangerous to farm workers than conventional ones. By the end of the book, he finds himself in a more nuanced place: "The art of celebrating humanity and nature," he concludes, depends on "having the courage to embrace paradox." His quest to puncture the myth of the natural turns out to have been dogmatic in its own way.

In acknowledging this, Levinovitz hits on something important. When deniers take up arms, it's tempting to follow their lead: to use science to build an open-and-shut case that strikes with the finality of a courtroom witness pointing out a killer.

But as Galileo knew — and as Levinovitz ultimately concedes — science, in its endlessly unspooling grandeur, tends to resist any conclusion that smacks of the absolute. "What only science can promise," Livio writes, "is a continuous, midcourse self-correction, as additional experimental and observational evidence accumulates, and new theoretical ideas emerge."

In their skepticism of pat answers, these books bolster the case that science's strength is in its flexibility — its willingness to leave room for iteration, for correction, for innovation. Science is an imperfect vehicle, as any truth-seeking discipline must be. And yet, as Galileo would have noted, it moves.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Shares