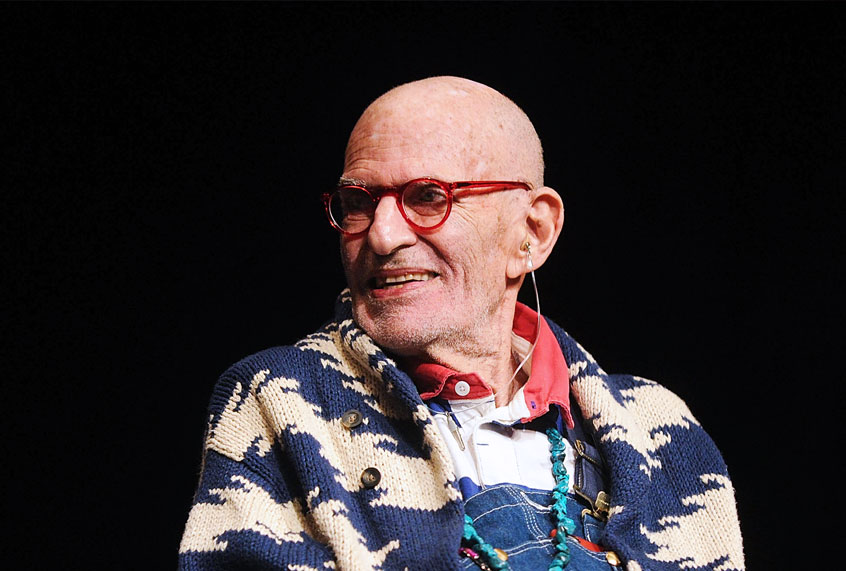

Larry Kramer, the award-winning gay author whose heroic activism during the AIDS plague saved innumerable lives and forever changed the health care system, died Wednesday morning in New York. He was 84.

David Webster, who married Kramer in 2013, confirmed the cause of death as pneumonia.

Decades ago, Kramer used his signature brand of activism to shock a Republican administration into treating AIDS as a public health crisis, although at the time it largely impacted gay men and other marginalized groups. As the founder of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), Kramer created a grassroots model for changing health policy that became an international movement.

RELATED: Larry Kramer: What Pride means to me

“We have lost a giant of a man who stood up for gay rights like a warrior,” rock legend Elton John said in a statement. “His anger was needed at a time when gay men’s deaths to AIDS were being ignored by the American government.”

Activism and Illness

It was far from Kramer’s first battle with illness. Webster married Kramer in the intensive care unit of NYU Langone Medical Center 2013, while the author was recovered from surgery after a bowel obstruction. Kramer contracted HIV during the 1980s epidemic and later required a liver transplant. He came close to death on at least three previous occasions.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, connected Kramer to an experimental drug trial after his liver transplant. The pair would rekindle their contentious and interesting friendship during a new plague: the novel coronavirus, which has now claimed the lived of more than 100,000 people in the U.S., apparently passing that milestone on the day of Kramer’s death.

Kramer publicly shamed Fauci as “an incompetent idiot” with blood on his hands in The San Francisco Examiner in 1988. As an activist, he frequently pushed the envelope and did not value delicacy or politeness. Though he co-founded the first AIDS service organization in the country in his living room, Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), it later removed Kramer from its board because of his confrontational brand of activism. He publicly shamed them as “a sad organization of sissies.”

RELATED: Larry Kramer: The problem with gay men today

And when Kramer, who was described by novelist, critic and GMHC co-founder Edmund White as an “Old Testament prophet” spoke, righteous anger was heard. Generations of gay men credited him with saving their lives. In an interview with The New York Times, Fauci put some of Kramer’s achievements into context:

Mr. Kramer, he said, had helped him to see how the federal bureaucracy was indeed slowing the search for effective treatments. He credited Mr. Kramer with playing an “essential” role in the development of elaborate drug regimens that could prolong the lives of those infected with H.I.V., and in prompting the Food and Drug Administration to streamline its assessment and approval of certain new drugs.

“Once you got past the rhetoric, you found that Larry Kramer made a lot of sense, and that he had a heart of gold,” Fauci said in an interview with The New York Times.

In his twilight, Kramer continued to fight for a cure for HIV, using his singular voice to the end.

“I’m approaching my end, but I still have a few years of fight in me to scream out the fact that almost everyone gay I’ve known has been affected by this plague of AIDS,” Kramer said when addressing the Queer Liberation March on the Great Lawn of Central Park on June 30, 2019. “As it has since its beginning, this has continued to be my motivation for everything I’ve done. It’s been a fight I’ve been proud of fighting.”

“I am a gay person before I’m anything else”

Kramer contracted a disease which disproportionately impacted gay men, and he proudly identified as a gay man before all else. That identity would go on to inform his career as a writer, which spanned decades and included numerous accolades.

“I am a gay person before I’m anything else. I’m a gay person before I’m a white person, before I’m a Jew, before I’m a writer, before I’m American — anything. That is my most identifying characteristic, and I don’t find many people who would say that,” Kramer told Salon’s Thomas Roberts in 2011. “The polls say the same thing: People do not identify themselves as gay. And that’s too bad. In fact, it’s tragic. It will prevent us from ever having what we deserve, I believe.”

In his twilight, Kramer reaffirmed this position in his Central Park address. He first shared the transcript of his speech with Salon.

“I love being gay. I love my people. I think in many ways we’re better than other people. I really do,” he said. “I think we’re smarter, and more talented and more aware of each other. And I do. I do. I totally do.”

“If I couldn’t write, I would die”

While Kramer’s activism is an intrinsic part of his legacy, he was a writer at his core. Friends know the hours Kramer spent sitting and typing at his computer, with books for research stacked in piles across his apartment. And he continued to compose until the very end. At the time of his death, Kramer was writing another new play about three plagues: HIV/AIDS, COVID-19 and aging.

Dr. Larry Mass, who co-founded GMHC with Kramer, revealed in an interview with Salon that one of the final things Kramer wrote in an email to him was a phrase he had repeated in prose for decades: “If I couldn’t write, I would die.” For Kramer, writing was as fundamental as eating or breathing.

“Larry became highly valued by many for his activism, but no identity was deeper or more important to Larry than being a writer,” Mass said. “And no writer who ever lived was more serious about writing.”

Kramer’s first major success as a writer was the adapted screenplay of D.H. Lawrence’s novel “Women in Love,” which was nominated for an Academy Award. Glenda Jackson emerged victorious on Oscar night for her performance as Gudrun Brangwen, but the film has long been remembered for a boundary-pushing scene in which Alan Bates and Oliver Reed wrestled in the nude. Like the novel itself, which challenged Victorian ideas, the queer undercurrent challenged preconceptions about love when it hit theaters in 1969. Kramer spent $4,200 of his own money to secure the rights for the film, which he also produced.

Kramer’s semi-autobiographical novel “Faggots,” published in 1978, chronicled life in the gay community before the plague. Though the real-life tales of promiscuous sex and recreational drug use publicly exposed by Kramer roiled the community, it became one of the best-selling novels in gay fiction.

“There are few books in modern gay fiction, or modern fiction for that matter, that must be read,” Tony Kushner, the award-winning playwright of “Angels in America,” once said. “‘Faggots’ is certainly one of them.”

“The Normal Heart”

Kramer is perhaps best remembered for “The Normal Heart,” which was chosen as one the 100 best plays of the 20th century by the Royal National Theatre of Great Britain. The play chronicles the onslaught of the AIDS outbreak and the formation of GMHC through the eyes of his alter-ego, Ned Weeks. The play debuted off Broadway in 1985 and proved it stood the test of time with its long overdue bow on Broadway in 2011.

“Your eyes are pretty much guaranteed to start stinging before the first act is over, and by the play’s end even people who think they have no patience for polemical theater may find their resistance has melted into tears,” New York Times theatre critic Ben Brantley wrote in his rave review. “No, make that sobs.”

That 2011 production was awarded the Tony for Best Revival of a Play. (Two years later Kramer was later honored by the American Theatre Wing with its prestigious Isabelle Stevenson Award for his humanitarian efforts.) Kramer adapted his play for the screen for a film directed by Ryan Murphy, with Mark Ruffalo playing Weeks. It won the Emmy Award for outstanding television movie.

“It was the greatest honor getting to work with you and spend time learning about organizing and activism. We lost a wonderful man and artist today,” Ruffalo tweeted upon Kramer’s death. “I will miss you. The world will miss you.”

The play’s sequel, “The Destiny of Me,” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

The “American People” series

Kramer’s magnum opus would become his “American People” series, which retold the story of the United States through the eyes of LGBTQ people, a community often erased in historical accounts. He spoke about his inspiration for the work in an interview with this writer in 2015.

“We haven’t ever had a history of homosexuals in this country since the beginning of this country, and all histories have been written by straight people,” Kramer said at the time. “They don’t include gay people. They don’t include, obviously, elected officials or presidents who were gay. Not that they would have necessarily [been] recognized in the way that we can recognize they were gay. And I just said, ‘It’s time. You know, I’m tired of reading history books in which we’re not a part of the history.'”

The series roused literary critics and historians over its claims that major historical figures, from founding fathers Alexander Hamilton and George Washington to Abraham Lincoln and the Mark Twain, were gay or at least had same-sex relationships.

“It’s a mess, a folly covered in mirrored tiles, but somehow it’s a beautiful and humane one,” Dwight Garner wrote in The New York Times. “I can’t say I liked it. Yet, on a certain level, I loved it.”

Kramer called out critics such as Garner for reviewing him and not the book, a criticism which Mass echoed after learning of his dear friend’s passing. Mass, the author of “Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America,” called the “American People” series “one of the greatest stories ever told” in his review of the nearly 1,700-page work.

“Despite his fame, it was Larry’s fate to be Cassandra, to be initially ridiculed and rejected for telling his truth. This happened again in response to the two volumes of his satirical, historical novel, ‘The American People,'” he told Salon. “My fondest wish for honoring Larry’s memory is that critics, historians and readers will take this writing that occupied the last half of his life more seriously.”

Kramer in love

“We Must Love One Another or Die,” Mass aptly titled his book about Kramer. In “Confessions,” he gives Kramer the pseudonym DJ Love. Both reflect a unifying theme which carries through all of Kramer’s work: love.

“Larry was all about love. It was about good love and bad love and thwarted love,” Mass told Salon. “Love is the motivational force.”

Kramer is survived by his love, Webster, and their beloved dog, a Cairn Terrier named Charlie.

In 2015, Larry Kramer and Joseph Neese spoke about “American People” and gay culture in his living room. You can watch more below via MSNBC: