I am almost 80 years old, with diabetes, high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol. I’m a little overweight, I had recent heart-stent surgery and I live in Fairfax County, Virginia, which has the highest rate of coronavirus cases in the state. Also an African, I feel that the virus circle is slowly tightening around me.

Recently, I wrote a will to my family: If the virus attacks me, I wrote, “Please stay away from me, alive and dead.” We will pray for the last time at a six-foot distance. I will drive my car to nearby Fairfax Hospital, report to the emergency office and start texting — no emotional phone calls — about the developments.

If I die, I told them, please make arrangements for my cremation: no funeral, no burial and no mourning gathering. When the virus disappears, please bury my ashes in a grave in the Muslim section of King David Memorial Garden in Falls Church, Virginia.

But then, a few days ago, I remembered a public promise that I made 12 years ago.

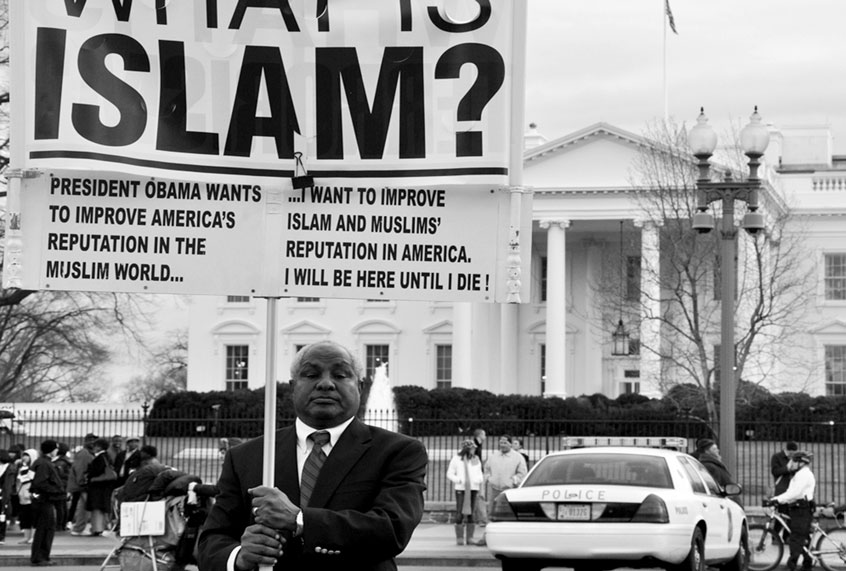

In 2008, as George W. Bush was leaving and Barack Obama was entering the White House, I started an irregular and lonely vigil that I called “silent jihad” in front of the White House, carrying a large banner with “WHAT IS ISLAM?” on one side, and “WHAT IS TERRORISM?” on the other side.

In small print on each side it read: “Obama wants to improve America’s Image in the Muslim World. I want to Improve Muslims’ Image in America. I will be here Until I Die!”

A journalist all my adult life, and a full-time correspondent in Washington since 1980 for major Arabic publications in the Middle East, I have always been a reporter. Those signs were the first time I had indulged in spreading an opinion. After a few years covering the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, and the subsequent U.S.-led Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) that involved the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, I became convinced that the GWOT had — has — been but a subtle and indirect war on Muslims, if not on Islam.

It became endless, aimless and frontline-less; about a million Muslims have been killed so far; millions of Muslims have been arrested, tortured, chased, harassed, insulted and humiliated all over the world. And the word “terrorism” became synonymous with Muslims, probably forever, or at least for a long time.

But in 2016, I completely ended the irregular vigil, although I had faced few harassments and only one physical attack that was immediately thwarted by the White House security guards. I was scared by the rise of presidential candidate Donald Trump and his campaign against foreigners, black people, Latinos and Muslims.

A “quadruple minority” (Muslim, Arab, African and foreign), I became afraid, not of a physical push or damage to my banner, but of someone who would come close to me, take a pistol from his pocket and shoot me in the face.

That fear did not come out of nothing: Extreme white supremacist groups were not only attacking Obama because of his color, but also appearing at some of his rallies carrying guns. After the Charlottesville riots of 2017, I knew the danger had been real.

Enter the coronavirus, and my new plan.

If I become infected, instead of driving to Fairfax Hospital, I shall bring up the banner bag from our basement, take a dark suit, a few clothes, some cash, a toiletries bag, a few blankets, and my many prescriptions — ready to live in my car somewhere near the White House.

As before, I will not be a stereotypical demonstrator: No shouting or marching. No chaining myself to the White House fence. No talking, except brief answers if I am asked direct questions. Believing that my appearance is part of my message, I will wear no T-shirts, shorts or jeans, but a dark suit — now with a mask.

Every morning, I shall take out the long golf bag that I bought in 2008, with the four-by-two-foot plastic banner inside. I had the words printed at a FedEx store, and bought wooden posts, clips and screws at Home Depot to hoist the banner. I also attached two wheels to the bottom of the golf bag, to make it easy to roll it with the heavy load inside it. In the bag, there is a small foldable stool to sit on. I didn’t use that before, but I probably will this time.

If my health deteriorates, I may be taken to a hospital by ambulance, or I may collapse in front of the White House — both serve to move toward fulfilling my promise.

Now, as I wait, I have mixed feelings.

On one side, in addition to the fear of death, I feel sad to die soon because I am working on a memoir project, and because I planned to return to my White House vigil when Trump leaves, or moderates his policies.

On the other side, I feel the responsibility, and the importance, of the promise I made in 2008: “Until I Die!” I remember relatives, friends and internet followers who supported me, and expressed their respect. This makes me feel calmer, and prouder of myself.