Many women in STEM are treated “like trash,” and as if they “don’t belong there.” If they do pursue a career in science, women are often subjected to harassment, ignored, and spend an inordinate amount of time navigating oppressive systems. For women of color, the efforts to prove oneself are compounded by additional unwelcome and unnecessary microaggressions.

The compelling documentary, “Picture a Scientist,” which was scheduled to have its World Premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, and will now be available in virtual cinemas June 12-26, is a case study of three women in STEM professions that seek gender equality, visibility, and diversity in the discipline. Biologist Nancy Hopkins, geologist Jane Willenbring, and chemist Raychelle Burks, all recount experiences with sexism, workplace harassment, microaggressions, and discrimination — as well as the gender pay gap — because they are among the too few women in a male-dominated environment.

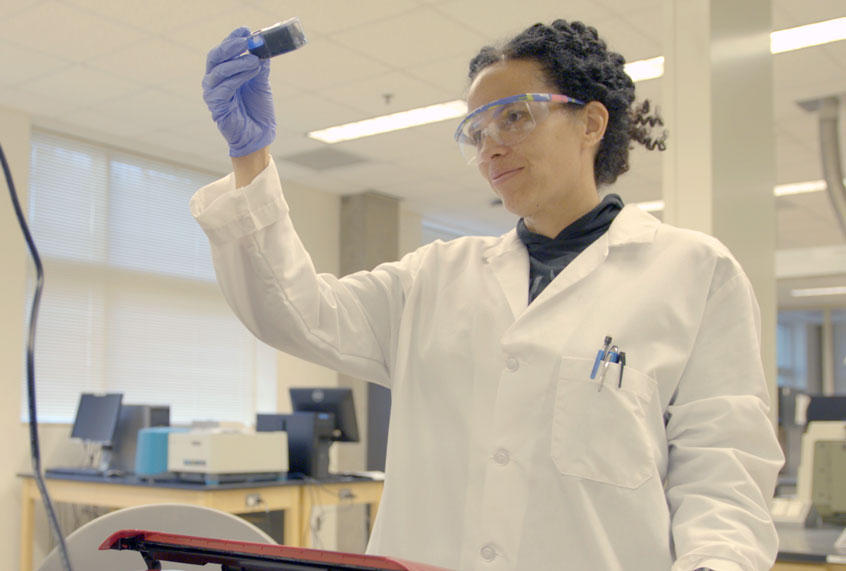

Filmmakers Sharon Shattuck and Ian Cheney lay out textbook cases and show the various strata of an “iceberg” to illustrate how women are mistreated in STEM fields. Hopkins fights for equality at MIT by literally measuring the proportional imbalance in lab spaces for female and male scientists. Willenbring files a Title IX complaint against Dr. David Marchant, who physically and verbally abused her on a field study in Antarctica. And Burks, who is Black, fights for diversity and against implicit bias, and repeatedly has to explain that she is part of her university’s faculty and not a member of the janitorial staff.

Shattuck and Cheney spoke with Salon about their new film and why women in STEM are subject to implicit bias and oppression.

What was your criteria for the stories you told? How did you find the three main case studies?

Sharon Shattuck: We knew we wanted to have an experience like Nancy’s that started in the 1960s and spanned decades. And we talked with Jane, who has more experience with sexual harassment. The women from MIT were comfortable talking about discrimination, but the #metoo angle started in the past few years. Raychelle’s story was important to focus on because that was “under the iceberg” — the microaggressions. When you try to tell one story, folks might say, “That’s not a big deal,” or “Just ignore it,” but looking at it in the context of the iceberg and how powerful it can be for these discriminatory stories.

Ian Cheney: We wanted a diversity of story across space and time, and across biases and harassment.

Burks said the overt instances of sexual harassment are brutal and need addressing but let’s not forget to shine a spotlight on the myriad everyday slights. We were trying to put together a sense of how is it that so many women are driven out of science. What’s going on? Through a lot of conversations with scientists we got a portrait of the culture of science that is — to put it mildly — not as welcoming as it should be. So how do we wrap our heads around that to put it into a film?

You cleverly let the story unfold as if you were teaching a textbook. Can you talk about the approach to the narrative, which establishes these women and then builds on their cases?

Shattuck: We wanted it to be story driven. Hearing personal stories is effective. These women have had amazing careers and have persevered. But we wanted to shine a spotlight on the science and learn about implicit bias. We wanted to put the science out there as proof of what’s happening as opposed to “she’s unlucky.” When you look at the science, you see it’s not bad luck but a systemic problem that underlines their experiences.

Our other approach was to follow our main characters to see them at work doing their science. It was amazing to see how much they lit up when they were actually doing their work. It’s hard for scientists to talk about their discrimination and feeling like they don’t belong. I come from a science background, and I never want to acknowledge any gender discrimination. I could sense how hard it was to talk about because they didn’t want it to undermine their roles as scientists or be seen as “less than” in terms of their science. I don’t think they are, but I understand where they are coming from. I was grateful they opened up to us about their personal lives.

What appealed to me was how each of these women had role models, even it if was Lt. Uhura on “Star Trek.” I like the line in the film about role models, “I want to be someone I needed when I was younger.” What are your thoughts on mentoring women in science; some of that is fraught with harassment?

Shattuck: Mentorship is important for any scientist. Jane has a great mentor in high school. He was a fossil beetle scientist and he said to her, “You should consider geology,” and encouraged her to start working in the field. One story we weren’t able to fit in the film was the case where a student was almost done with a PhD but because of harassment, they had to leave their mentor and either start over or leave the field. That’s a huge problem.

Cheney: We came to see mentorship as a more complicated idea that we originally had. On the one hand, we need better mentors, and they shouldn’t harass their students. But there is something structural about mentorship in science that needs a second look. That’s shifting in the culture of science right now. Perhaps a doctoral student shouldn’t be entirely dependent on one thesis advisor — that there should be checks and balances there, so power doesn’t become a force. Maybe mentoring isn’t working? How that works made us think differently about our work.

Many of the women interviewed in the film talk about receiving unwanted sexual attention, being excluded, not getting credit, being ignored or criticized, experiencing microaggressions, getting a reputation (for sex, not science), and they are afraid to speak out if they want a career, or they are forced to leave science to avoid further issues. It is good that Nancy became a radical activist and that Jane filed a Title IX complaint, and Raychelle fights against the “angry black woman” trope. But they shouldn’t have to! What are your thoughts about why women are so threatening and how things have evolved over time?

Cheney: In a way, the yet-to-be-made sequel to this film is a deeper dive into the lives and minds of male scientists. What is it in the culture of male scientists in particular that is resistant or slow to change? I think for our film, focusing on centering the story on the three protagonists and telling things from their perspective, we got glimmers of insight into why it felt threatening for men to see women to rise in the sciences. Nancy says the discrimination ramped up after she got tenure. The better she did, and the more she rose in the ranks and within reach of more grant money and resources and lab space, the more difficult time she had. We heard this from a number of people. You could have an older male scientist mentor a younger woman, but as soon as chairs and grant money were at stake things really shifted.

Shattuck: The stories are shocking. But it is impactful to hear those stories firsthand. Because she’s a woman of color, Raychelle is asked if she is a janitor. I’ve never had anyone ask me if I was a janitor.

Cheney: The burden of always having to be a patient teacher is ever present, Raychelle says. It is a big drain on the careers of women in science to have to teach men not to grope them and to respect them as equals.

Shattuck: The burden should be on the people in power to use it for good. Not just on women to get into science. We are seeing encouraging signs. It makes science better. If everyone came from the same class and demographic, they will all have similar ideas. It benefits us all to have scientists from different backgrounds and cultures.

What do you think accounts for powers that be falling on the right side of history?

Shattuck: It did come down to a few good people at MIT. Chuck Vest [then President of MIT] cared about these issues and was able to do the right thing. There is power concentrated in the top of these organizations, but it’s good to be cognizant of your power and use it for good. Bob Brown, [then] provost at MIT, and now President of Boston University, used what he learned and applied it for good, with [David] Marchant. He’s been an advocate for women and minorities at Boston University.

Cheney: What are the levers for change at the highest levels? Maybe they are different on different time scales. On the short term, the old boy network changing quickly because of the potential for shame and litigation. We don’t want them to be the tools for righting things, but what we are trying to chip away at in the film was reprogramming our minds, so more men grow up thinking it’s normal and right for women to do science and be in positions of power. The levers are baked into the culture. Structural shifts need to happen — we need to stick with this work, not fix a few things here and there.

Shattuck: We put out in our press release that countries run by women and that have female scientists are doing well fighting COVID. There needs to be active change. Stay with these issues and pay attention to them. If they stop actively working on this at MIT, the number of women scientists will go down. You need to hire them.

There are also some real “follow the money” issues at play here with funding. But that does not give anyone the right to belittle, humiliate, discriminate, or discourage women from working in STEM. How do you process the behavior at work?

Cheney: We talked to a number of women scientists who said maybe we need to change the definition of what a scientist is and include it on someone who actively spends time working to better the future of science. Nancy was reluctant to be an activist — and she was reluctant to spend that time even though she did great things. Part of being a scientist is that part of the culture is how we treat them. It shouldn’t affect jobs, or grants, or being defined as a great scientist. I see a divide between those that focus on the science, but there are others who say that’s a luxury we can’t afford. If we put blinders on, that drives people out of science.

Shattuck: I can identify with each woman who asks themselves, “Do I speak out or don’t I? And when do I speak out? And how does that impact my career?” There’s no right answer to this. We’re all just figuring it out, even in this time of #metoo, you’re branded being in this group now if you decide to talk or not. I don’t think it has the same stigma, but there are trade-offs. You can’t judge someone for not speaking up. I hope as a society we move towards ways of mitigating these issues in academia. Create some first steps before filing a Title IX lawsuit. Systems we can put in place, like at a microlevel, before they escalate to a big, dramatic lawsuits.

Your film is certainly hopeful for change, but what are your thoughts about retaining women in STEM where 50 female students can enter a program and only seven stay through it to the end?

Shattuck: It’s not a matter of getting women interested in STEM. Women are interested in science, math, engineering, and technology, and that’s proven in the number of women coming into these fields. But the issue is why are women leaving? Looking up the chain at every university, it’s all white men. It has to do with the culture. It’s a combination of making women feel unwelcome, minimizing their concerns, and rewarding certain people and moving them up quicker than others. Words used to describe male scientists are “brilliant” and women are “team players.” We need to think about what we think about when we think about great scientists.

Cheney: Part of the answer may involve changing the definition of what it means to be a great scientist. In the media, we’ve had an image of great scientists that permits — or almost forgives — inattention to fellow humans, the lone genius who doesn’t know how to relate to people because he’s a genius. That’s the price to pay for their insights into humanity. But there are people who are shy and like to work alone but we need a definition of great scientist that not only compels them to be better to their colleagues and mentees but also incentivizes that and rewards scientists for actively trying to make science better. A great scientist can and should be a great person too, and that hasn’t always been part of the definition, and that’s part of the problem. It’s not their amazing lab and field work and contributions, it’s that they actively changing the culture of science for the better.

Check out the virtual Q&A for “Picture a Scientist” on June 17 for more on the conversation and watch the trailer for the documentary below: