Filmmaker Ivy Meeropol has already made a documentary about her family connection to history. As anyone acquainted with 20th-century radical history will already recognize, she is the granddaughter of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the supposed "atom spies" executed by the federal government in 1953. Meeropol's 2004 HBO film "Heir to an Execution" provides a moving, intimate study of that event and its personal and political legacy — although it does not and could not settle the question of the Rosenbergs' guilt or the fairness of their sentence, which remains contested to this day.

(Full disclosure, although I don't think it's relevant to this story: Both my mother and stepfather were American Communists, and my stepfather, Mel Fiske, knew Abel and Anne Meeropol, who adopted the Rosenbergs' children, including Ivy Meeropol's father, after their parents were electrocuted. So, yeah, if you want an entirely neutral account of these events, go elsewhere.)

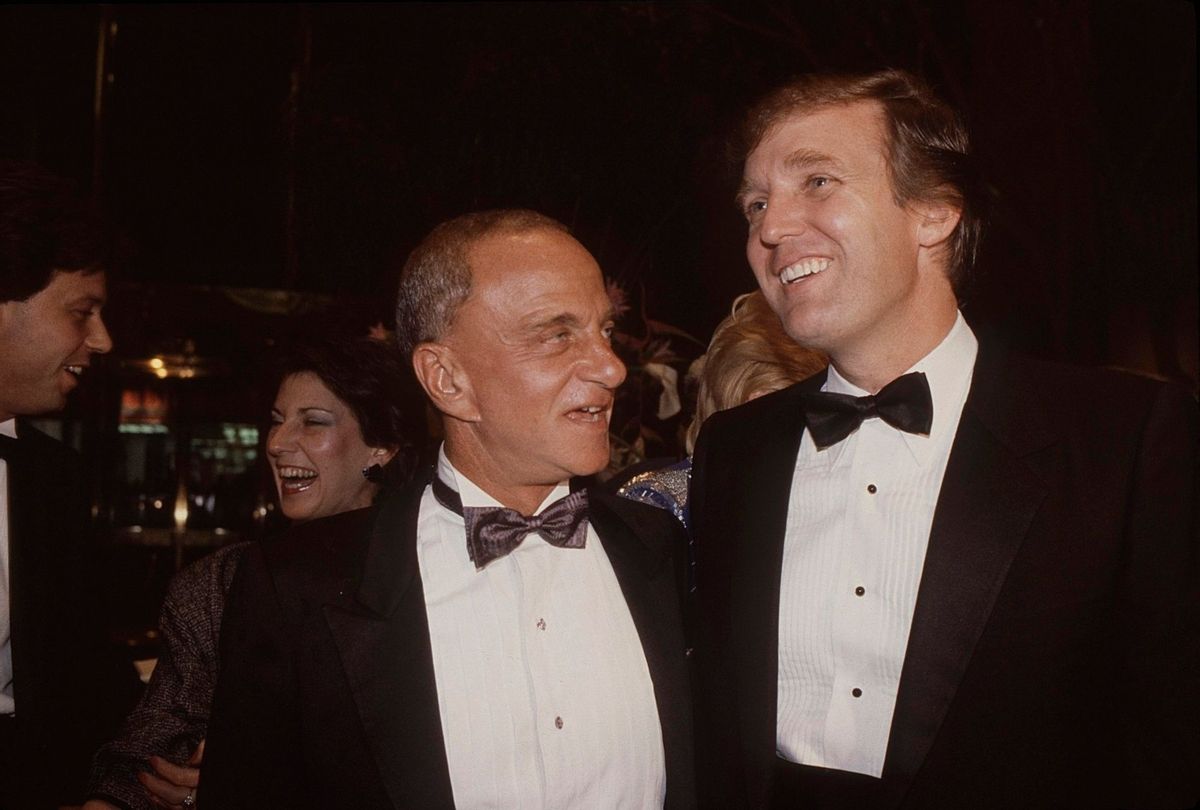

Meeropol's new film uses her grandparents' execution as an inciting event, so to speak, but it's only indirectly about them and about the combustible collision of Communism and anti-Communism in mid-century America. "Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn," which premieres on HBO this week, is instead about one of the most notorious Americans of the last century — the man who sent the Rosenbergs to the electric chair, who served as Sen. Joe McCarthy's right-hand man, and who groomed and nurtured a young New York real estate developer named Donald Trump, seeing in the callow womanizer and tabloid celebrity the seeds of greater things.

Few people shape history as much as Cohn did, and none of it was for the better. Given that, I told Meeropol in our phone interview this week, it's remarkable that "Bully. Coward. Victim." offers such a full, complicated and human portrait of Cohn — who may be best known in our age for his vivid satirical portrayal in Tony Kushner's play "Angels in America" (as variously played by Ron Leibman, F. Murray Abraham, Al Pacino and Nathan Lane, among others). Not many people would have gone out of their way to be fair to the man who almost literally killed her grandparents.

My recording software glitched out for the first few minutes of our conversation, but I can reconstruct Meeropol's answer fairly enough. She said that both as a storyteller and a human being, she thought it was important to pierce the mythology surrounding Cohn and depict him as a highly intelligent and almost uniquely conflicted person. Cohn was both Jewish and gay — and only partly in the closet, for the latter portion of his life — and at least initially identified as a liberal Democrat, yet made common cause with the anti-Communist crusade led by a right-wing Republican, which specifically targeted Jews and gay men as agents of the Red menace. (In the film, Tony Kushner observes that Joe McCarthy was too dumb to appreciate that Cohn was dragging him into a self-destructive conflict with the U.S. Army, which ended up destroying the Wisconsin senator's career.)

The film's title comes from a square in the AIDS Memorial Quilt that Meeropol and her father Michael (the Rosenbergs' eldest son) stumbled upon when the quilt was on display in the National Mall in Washington in 1987. Cohn had died of AIDS at age 59 less than a year earlier. Their father-daughter discussion in the film about that discovery offers one of the most powerful moments in what is both a piercing personal memoir and a work of scrupulous and even generous social history.

Then I asked Meeropol about the fact that nearly everyone involved in her grandparents' trial for treason — from the defendants and their attorneys to the key witnesses, the trial judge and of course Cohn, the lead prosecutor — had been Jewish.

You know, It finally dawned on me that in one sense the prosecution of the Rosenbergs was like something out of Philip Roth's "The Plot Against America," a show trial by which Jewish Americans could display their loyalty.

Oh, yes, absolutely. You know, back when I was making "Heir to an Execution," a Jewish film producer, I'm not going to say who, kind of told Sheila Nevins at HBO, who'd greenlit the film, "You shouldn't be doing this film. You should leave this story alone."

Wow. Because, essentially, it "wasn't good for the Jews"?

Yeah, even then. That was like in 2001 or 2002, when I was in the midst of making that film. "That's a black hole. That's a dark moment in Jewish history and you would do well not to revisit it." That kind of thing. So yeah, in terms of [the Rosenberg trial] it was absolutely calculated. Cohn embraced that and he spent his career making sure that he was clearly – because he was proud to be Jewish, but he really wanted to be certain that he was always identified as an anti-Communist.

You may not want to touch this question, but I was really struck by the presence of Alan Dershowitz in your film. I've met him and interviewed him myself, and he's such a peculiar individual. I'm well aware that in his youth he stood up for the rights of Communists at Brooklyn College, and has for much of his career been a civil liberties lawyer. But given his apparent slide to the right in recent years, and of course his strange relationship with Donald Trump, it was troubling to watch him on screen talking about Roy Cohn. I'm wondering how much any of that was in your mind.

Oh yeah, I mean, I wasn't necessarily excited by the idea of interviewing Alan Dershowitz because he'd already been publicly for Trump. I find him very confusing. I don't quite understand where he's coming from or if he's just a pure opportunist or what. But I felt that it was a really important interview to get. I went into that interview just really wanting him just to tell me his stories of Cohn, how he knew Cohn and what he knew of him. I knew that Cohn had admitted quite a few things to him about my grandparents' trial and what had gone down. I never expected Dershowitz to go as far as he did, in saying, ultimately, that it was the greatest miscarriage of justice in his lifetime.

It's an amazing moment.

Exactly, and to hear it from Dershowitz is important. It's not the usual suspects telling us this, which is easy for people to dismiss sometimes. "Oh it's just someone on the left, of course they're going to say that," right?

And then to have him be involved in the impeachment process was just like, oh God, there he is again.

Making bizarre circular arguments that I could not follow about how the president can't be impeached unless he's been charged with an actual crime, and he can't be charged with an actual crime because he can't commit an actual crime.

And then he was never to be heard from again after that day, right? He's one of the only people from the film who — I have no idea whether he saw the film, or if he did, whether he likes it or not. I did ask him if he had had a chance to see it and he never responded.

Was there anything that really surprised you either about Cohn or about the story in doing the research — stuff that you learned about him or about his life that you hadn't known about before?

I mean, probably the two biggest things that were most surprising were, one, that he fought so publicly against gay rights. I didn't know that. By the time the gay rights bill was moving through the New York City Council [in 1986], he was pretty well known in a lot of circles as being gay. Yet there he is, aligning himself with the Archdiocese of New York at the same time. I didn't know anything about that. So that was very surprising.

Then, I've come to learn how integral he was to Donald Trump envisioning himself on a national and even international stage. I knew, of course, about his connection to Trump. That was what made me want to make this film and actually decide to finally pursue it. But what we learned is just how important he was, in terms of where Trump got to, and even how we got to where we are now. I think just to see the machinations, the actual process of Cohn having these relationships with so many journalists. He had a close relationship with Lois Romano [of the Washington Post]. He says "You need to interview my guy Donald Trump, you're going to be seeing a lot more of him."

Then he's on this campaign: You see footage of him talking about how Donald Trump is a genius and this, that and the other thing. He's promoting him and helping him and he's introducing him to everyone he needs to know in Washington, who turn out to be people like Paul Manafort and Roger Stone. All those characters who end up helping him get to the White House. Rupert Murdoch, all these connections that originated with Cohn. I did not know the extent of his influence.

Yeah, that is obviously the big news hook in the film. There is also this sense, and I think you fill in the blanks on this really well, that maybe Donald Trump is nowhere near as bright as Roy Cohn, but he learned a number of tricks from him. Rhetorical tricks, public relations tricks, ways to position himself — maybe more than anything else the attitude of always attacking and never retreating. All those aspects that we see in the White House right now sound like things he picked up from Roy Cohn.

Absolutely, absolutely. I mean, even when Trump was being pressured about his relationship with Putin, he threw out my grandparents' names. He said, "Traitors? That's what Ethel and Julius Rosenberg are. That's what they did." That's exactly the kind of thing Roy Cohn would say to divert attention from himself. You know, we were thinking as a family, at the time, like, "Trump doesn't even know what the hell he's talking about." He probably only heard of them because of Roy. That kind of stuck with him and then he's able to say "That's a traitor. A traitor is a Rosenberg." Then his followers say, "Oh yeah, right, that's those Commie Jew atomic spies. That's what a traitor is, not Donald Trump."

That's just one small example of that kind of language. He certainly learned how to deflect and blame and gaslight and do all sorts of Roy Cohn things. Whenever I hear about the entire Republican Party being too afraid to challenge him, that's just like Roy, who would threaten to expose people to try to get a settlement. There's Trump threatening to tweet you into oblivion.

Just this week, when we have the extraordinary spectacle of people like white Southern evangelical pastors standing up and saying, "Well, maybe it is time to take these monuments down." And Donald Trump, who isn't from the South and doesn't have any investment in this stuff, is like, "No way, this is about winning and greatness and history." Because you never admit you're wrong.

Yeah, or his decision to speak in Tulsa on Juneteenth. That to me is classic Roy Cohn.

Obviously you have already made a film about your grandparents and what happened to them. That story is certainly an important part of this narrative, but you made a decision here to bracket that a little bit. It's the thing that launched Roy Cohn's career, but maybe in some ways not the most important part.

I'm glad to hear you say that, because I took great pains to not make this film so much about my family and to be "Heir to an Execution Part II" or whatever. I kept reminding my whole team, and myself, that this was the beginning of his career and we want to cover a lot of it. Of course we could use more of the story because of how Roy trailed my father and my uncle as they were trying to reopen the [Rosenberg] case. He became the face of the government defending the execution. But I never wanted this film to really just be about that.

Our family's story was just so dramatic and tragic and emotionally raw that it could easily dominate. This is the story of Roy Cohn. I mean, my family's story is important, to understand how he got his start. It also is important to understand how he would break the rules to get whatever he wanted, with reckless disregard and contempt for people's lives. He did that time and time again in so many different venues, so many different periods of his life.

I didn't want it to dominate so much. I was cautious and careful about not seeming like this is our family revenge story. That's not as important in my mind. I wanted to make sure that it never came across that way.

Let me ask you a different version of my opening question. You had every reason to hate this man, and you've gone out of your way to create a fair and full portrait of one the most widely vilified Americans of the last 100 years. What do you hope audiences can get from that portrait?

I think my effort to empathize with Cohn is about trying to humanize him as someone who was not purely evil but was also tortured by his own inability to live openly as a gay man. You can clearly see that he was happier when he could, in those periods of his life where he could escape to Provincetown and other places. I think it's important to not just leave it that he was evil.

It limits how we can overcome systemic homophobia, racism and the like. Because if we just dismiss him as this self-loathing, evil person, we don't actually get to understand the sense that he's a human being who wished, I'm sure somewhere inside, that he could live a life where he was happier, where he could be free too. I think it's a powerful thing for us to try to understand that.

It's not about forgiveness. It's about trying to understand what he went through, so we can look at what is systemic and not just kind of a one-off. It's not just one person being evil. It is many people suffering because we're not protecting them, we're not embracing them, we're not celebrating diversity. We are crushing people's spirits when we don't protect them.

So Roy Cohn is an example that we can learn from. We can only do that by humanizing him. I really believe that if you just call someone evil it dehumanizes them, and then we're doing exactly what he did. We're doing what Trump does when he calls people "thugs" who are fighting for Black Lives Matter or any other social justice or progressive movement where people are dismissed, like my grandparents were, as evil Commie spies. It dehumanizes them. I don't think we should be doing the same thing to someone like Roy Cohn.

One last question, and given our personal backgrounds I'm sure we could talk about this one for hours. How do you think now about the legacy of American Communism and anti-Communism, as it continues to resonate below the surface of our public life?

Wow. Yeah, we could talk for a long time on that one. I mean, it's so interesting to me that someone like Trump and his followers so easily fall into this old language of like "Oh, my god, that's socialism, that's communism, so bad, so bad." Meanwhile, there's this surge of young people who recognize that the core values and beliefs and political aspirations of those movements, so much of it is exactly what people are still fighting for today. It's equality and social justice and equal access to public education. It's not accepting that it's OK that we're continuing to lynch Black Americans, with police officers doing just that. I hope the history of the American Communist Party will lead to young people looking to understand where people like my grandparents were actually coming from. It's what I tried to do in "Heir to an Execution."

I wanted so much to redeem the core values and take it out of the simplistic ways that the Trump administration will use the language to divide us. I see a real opportunity now for people to revisit those same ideals. In "Heir to an Execution" I have Miriam Moskowitz, one of my characters, saying of that time period, "You have to be dead from the neck up not to feel radical, not to feel like a change is necessary." Right? That's where we are right now. And what's even more exciting is that all these young people are feeling it.

"Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn" is currently streaming on HBO Max.

Shares