It sounds like the start of a joke: What do Korean pop music fans, video meme apps, and the president of the United States have in common?

It turns out quite a lot.

During the build-up to President Donald Trump’s reelection rally in Tulsa, Okla., the K-pop fandom and TikTok users urged their followers to reserve hundreds of thousands of tickets to the event, even though they had no intention of attending.

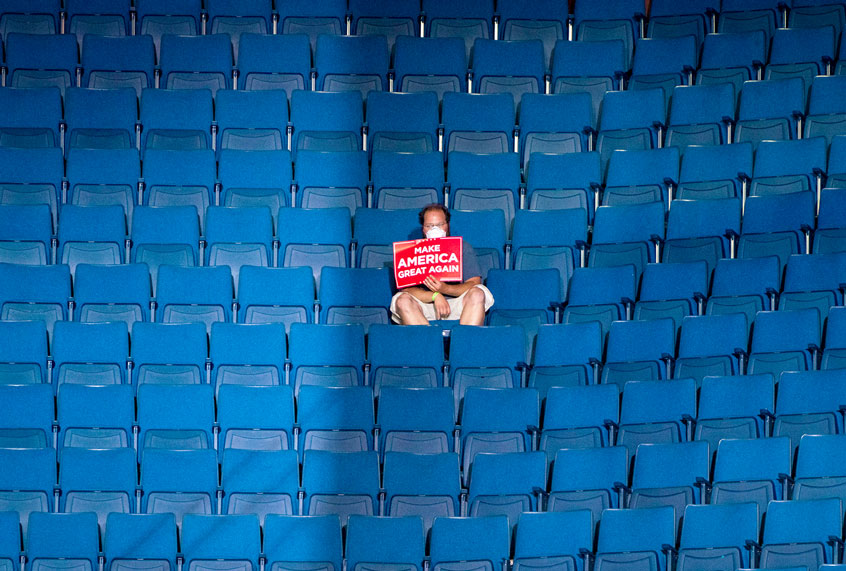

This could have been little more than a low-profile online prank. But when Trump’s Saturday rally rolled around, the Tulsa Fire Department estimated that only 6,200 people showed up at the Oklahoma Bank Center, which has a seating capacity of 19,000. It is impossible to know for sure how much of this was due to the trolling campaign, but from a PR standpoint it was a major humiliation for the Trump campaign — and a public relations triumph for online activists.

TikTok, a video social media site akin to Vine popular with Generation Z and millennials, has a major subculture of politically active, mostly left-leaning users who often organize through the ephemeral app. The political leanings of Western K-pop fans, who are also largely young, are more multifarious; though perhaps unsurprisingly, the fandom has a pluralistic and multicultural bent, which puts them in opposition to Trump.

The rally prank movement began when Mary Jo Laupp, a 51-year-old grandmother from Fort Dodge, Iowa, suggested in a TikTok video that her fellow TikTok users reserve tickets and then not show up as a way of protesting the racial injustices perpetrated by the Trump administration. Laupp — who worked on several rallies for the Democratic presidential campaign of South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg — told The New York Times that she was inspired after seeing African American TikTok users voice outrage over Trump holding a rally on Juneteenth (a holiday celebrating the abolition of slavery) in a city notorious for one of the bloodiest race riots in American history. (In response, Trump’s campaign pushed back the rally by one day.)

Laupp told the Times that she was “overwhelmed” and “stunned” by the fact that her video was so effective. “There are teenagers in this country who participated in this little no-show protest, who believe that they can have an impact in their country in the political system even though they’re not old enough to vote right now,” she said.

Laupp’s call to arms spread throughout social media platforms like Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter. Many users did not simply reserve tickets, but concealed their activities so that the Trump campaign could be duped into not noticing that their record numbers were artificially inflated. Participants in the trolling campaign often deleted their posts within 24 to 48 hours to cover their tracks. Their low profile approach seemed to fool Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale, who tweeted days before the event that they had “just passed 800,000 tickets. Biggest data haul and rally signup of all time by 10x. Saturday is going to be amazing!”

19-year-old Diana Mejia, who was instrumental in moving the campaign from TikTok to Twitter, told NBC News that “it was kind of like our own form of protest in a way because we were able to get a million requests and most if it was not the people who were planning on going.”

As 26-year-old YouTuber Elijah Daniel told the Times, “It spread mostly through Alt TikTok [the subversive, anti-capitalist subculture outside mainstream TikTok]— we kept it on the quiet side where people do pranks and a lot of activism. K-pop Twitter and Alt TikTok have a good alliance where they spread information amongst each other very quickly. They all know the algorithms and how they can boost videos to get where they want.”

Daniel’s reference to K-pop activism is noteworthy, since fans of Korean pop music have recently emerged as not only generous donors to Black Lives Matter and related social justice causes, but also as some of the cleverest social justice activists on the internet. When the Trump campaign announced that it wanted the president’s supporters to send him happy birthday wishes on June 8, K-pop fans overwhelmed them with prank messages that referred back to their favorite music idols. After the Dallas Police Department sent out a call for citizens to record Black Lives Matter protesters engaging in suspicious or illegal activity, K-pop fans on Twitter deluged them with so many “fancam” videos that the dedicated app eventually crashed.

In numerous instances, when racist hashtag campaigns began to trend online, K-pop fans coordinated to overwhelm hashtags like #WhiteLivesMatter, #WhiteoutWednesday, #MAGA and #BlueLivesMatter by spamming them with K-pop videos. Their goal was not only to annoy racists, but to make it more difficult for them to utilize social media platforms to connect with each other and thereby mobilize. In the process, they also redirected attention back to anti-racist protest activities.

“As a K-pop reporter who has covered the industry for two years, I am delighted to witness the world finally recognize fans of K-pop artists for who they are: a social-media-savvy and politically aware group of people who should not be underestimated,” Yim Hyun-su, a pop culture reporter at Korea Herald, wrote in The Washington Post earlier this month (and prior to the protests). She argued that K-pop fans have been underappreciated for a number of reasons, including sexism against a fanbase associated with “fangirls” by some and the fact that “the gamer and streamer communities have been taken a lot more seriously by the media.” Yet she noted that “the global K-pop fandom consists of people from varying age groups, of different ethnicities, from all walks of lives, many of whom are part of the LGBTQ community.”

TikTok has also become a hub for activism. Users helped spread awareness of racist police brutality using the #blacklivesmatter hashtag, sharing educational resources and trading advice on how to protest safely. Taylor Cassidy, a 17-year-old in New York, told Reuters that “because the BLM movement has been present in society for such a long time, my generation has been able to use TikTok to spread awareness through the lens of a young person’s mindset.”

TikTok has also been used to draw attention to issues such as income inequality, teachers’ rights, transgender rights, indigenous rights and issues, and climate change. The company has incurred some controversy over accusations that it has taken down videos supporting the Hong Kong protesters, though the company told the BBC that “TikTok does not remove content based on sensitivities related to China. We have never been asked by the Chinese government to remove any content and we would not do so if asked.”

In the case of Trump’s sparsely-attended Tulsa rally, it may not be possible to say with full confidence that an alliance of K-pop fans and TikTok users were entirely responsible, though their efforts certainly helped. Other factors that may have played a role, such as concerns about the coronavirus pandemic and dampened enthusiasm for the president, who is floundering in the polls.

Yet the Trump campaign has not been able to provide a convincing explanation for why their reservation numbers were so high: Parscale pointed out in a statement that the rally was general admission based on a first-come-first-served basis, and as such the false reservations would not have impacted attendance in the auditorium, but could not explain why the campaign boasted about having 800,000 reservations if they suspected many of them were bogus.

“Leftists and online trolls doing a victory lap, thinking they somehow impacted rally attendance, don’t know what they’re talking about or how our rallies work,” Parscale said in a statement. “Reporters who wrote gleefully about TikTok and K-Pop fans — without contacting the campaign for comment — behaved unprofessionally and were willing dupes to the charade.” He pointed the finger of blame at Black Lives Matter protests, the coronavirus and the media.

For his part, Trump acted like a man trying to spin away a terrible embarrassment. During his speech he praised the sparse crowd as “warriors” for showing up, attributed the low turnout to “thugs” and claimed that there were “very bad people outside” doing “bad things” that kept attendance low. (Reporters at the rally did not observe any violent protesting or efforts to physically impede rally attendance.) He attacked the “unhinged left-wing mob” for its recent protest activities and taking down of Confederate statues and intimated that his supporters could engage in violence against them, saying that “our people are not nearly as violent, but if they ever were, it would be a terrible, terrible day for the other side.” When later describing the rally on Twitter, Trump wrote that “THE SILENT MAJORITY IS STRONGER THAN EVER BEFORE! #MAGA” while showing misleading photographs that depicted a packed auditorium.