Following weeks of global protests, a divided country, and millions in damages, all of the officers involved in the police killing of George Floyd have now been charged. This is just a small victory though, and a long way from true justice.

In the past month, America at large has finally woken to the injustice that Black communities have been protesting for years, decades, centuries. While white people try to wrap their minds around what racism actually is and how it’s not just the police that are responsible for these deaths and inequities – but an entire system – it helps to examine the context of another police killing.

It’s been five years since Freddie Gray died as a result of injuries he received while in police custody. And like Floyd, Gray’s death sparked a series of protests, looting and grassroots movements that garnered both national and international attention. The sum of these violent and nonviolent activities will forever be known as the Baltimore Uprising. The cops who killed Gray were charged, just like Floyd’s killers; however, they all won or had their trials dismissed. They received back pay and are all currently employed by the Baltimore Police Department.

Since then, Baltimore has continued to have problems –– going viral for all of the wrong reasons including a record number of homicides, department-wide police corruption, five new police commissioners in under five years, the “Healthy Holly” children books scandal with former Mayor Catharine Pugh that netted her over a half million dollars but was followed by stint in federal prison – just to name a few, leaving many people asking, “What’s up with Baltimore?”

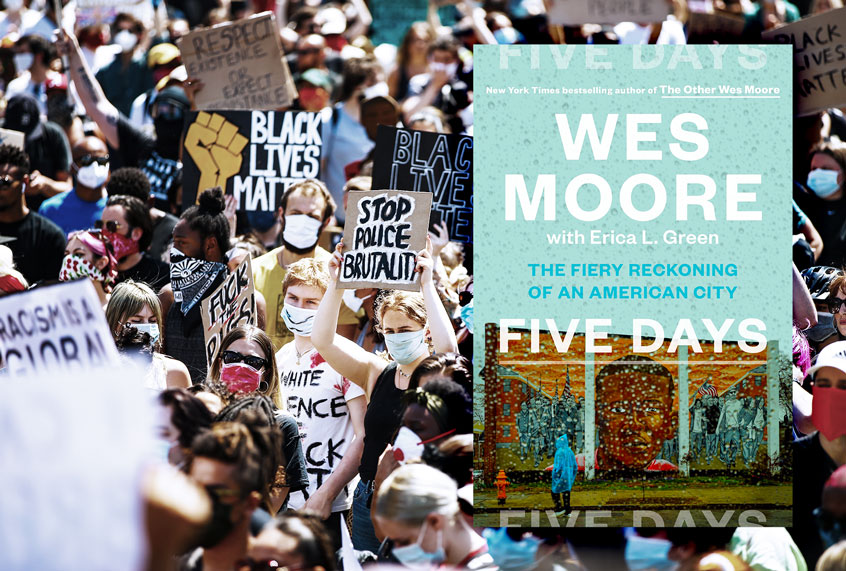

Wes Moore, a Rhodes Scholar, bestselling author and CEO of Robin Hood – one of the largest anti-poverty nonprofits in the nation – attempts to get to the root of those issues in his new book, “Five Days: The Fiery Reckoning of an American City.” Moore has had a front row seat to all of this corruption as a Baltimorean. Rather than offer a critique from his own lens, Moore decided to follow a series of Baltimore residents from different walks of life as they became aware of the Uprising –– where they were, what were they doing, how did it affect them and what their responses were.

You can watch my “Salon Talks” episode with Wes Moore here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below to hear more about what the city needs to heal, why changing failed systems trumps replacing leadership and the role he and Robin Hood are playing in eradicating poverty. The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

COVID-19 has had a massive impact on joblessness. Poverty is your big issue at Robin Hood. What’s going on?

When people talk about what impact on what percentage of the portfolio, whatever, has been impacted by COVID, the answer actually for me is really easy. It’s all of it. This thing has had a disastrous impact on our community. It’s not just the health implications, the fact that this thing has attacked Black and brown folks at double the rate in terms of actual transmission, but also death rates. But, it’s the economic implications.

It’s actually been a really important moment when I even think about the role that Robin Hood and any organization that’s in the poverty-fighting space really plays in this because we have to be able to approach it with a real level of humility. We’ve watched 11 years of job growth go away in 11 weeks due to this thing. Eleven weeks has just knocked it out. We’ve watched the fact that 23% of all jobs that have been lost due to COVID-19 were people who are already living in poverty. Think about that: 23% of people who have lost their jobs because of COVID-19 were living in poverty before COVID-19, i.e. these are the working poor. These are the ones who were working jobs, in many cases multiple jobs, and still living below the poverty line. This whole idea and this narrative, when you hear people talk about, “They should just get a job.” How about the majority of them had jobs, and just weren’t getting paid enough, were still living below the poverty line?

For Robin Hood, we’re one of the largest organizations in the poverty-fighting space in the country. When you talk about what has been the impact of COVID, we’ve never seen anything like this, and particularly in the speed that this thing is going to have on our communities. While philanthropy is going to have a really important role to play, our social organizations are going to have a really important role to play. The truth is that they are not going to be million-dollar solutions to trillion-dollar problems. We’ve got trillion-dollar problems.

What a time for all this to come when we have such poor leadership at the top. We’ve got a president who takes these things as a joke.

We’re talking about something where the danger about COVID is that it has attacked the most vulnerable. When people say, “COVID impacts everybody,” true. However, it’s not impacting everybody proportionately. This thing attacks the most vulnerable. It attacks people with preexisting conditions. It attacks children who are growing up with asthma. Which, by the way, if you look at West Baltimore, almost half of the kids are suffering from asthma. It attacks people who have heart disease. It attacks people who have diabetes. That’s the danger. That is the real danger when we’re talking about COVID-19. Two-thirds of all the jobs that have been lost have been people who’ve been within service industries — restaurants, hotels, that type of thing. Who’s making up those jobs? That’s us. A lot of those jobs are the low-wage jobs, the entry-level jobs. These can be the most difficult for people to be able to recover from. This is economic injustice. We have to be able to be honest about the fact that we’re not just dealing with these individual pieces that we need to fund in organizations that we need to, these are structures that we have to be able to upend. These are systems that we have to be able to reinvent and reproduce.

With that, and acknowledging that many of these systems have problems, there’s been a lot of talk about defunding police and trying to reallocate some of those funds into places that will be more beneficial to communities of color. Where do you stand on that?

It’s interesting, because I want people to understand . . . the reason why these conversations are even happening. Take a look at the budget for Baltimore City alone. If you look at the health and wellness budget for Baltimore City, it hovers at around, what, $42 million. The budget for the police department is, what, $509 million? I just want people to have context in what we’re talking about here. We’re talking about a distinct reality where, if you look at budgets, what budgets fundamentally are, they’re moral documents. They’re documents of, basically, you telling me what is important to you. What matters to you. What do you spend time on, and what do you then turn around and fund?

We can do it both with municipal budgets and we can do it with personal budgets. D, if you show me what you spend your money on every month, I can tell you what’s probably important to you. Same thing with me. If I show you what I spend my money on, you probably get a sense of, “Okay, X is important to Wes. Y is important to Wes. Z is probably not important to Wes,” because I don’t spend a whole lot of money on it. You can get a sense, just simply looking at budgets. The reality is that we are getting a very clear indication about what’s important and what’s not important when we look at budgets. By the way, it’s our money, and money that’s being spent on our behalf.

I was actually talking with the folks from LBS, Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. We were having a conversation where I was like, “I’m very much aligned with what you’re saying.” It was like, “I don’t want to abolish the force, because I think there’s a necessity for having it.” But, do I think that we put far too much weight and far too much pressure, and we expand this definition of policing in a way that’s incredibly dangerous to communities? Absolutely. Do I think this excessive militarization that we have for policing is useful, or helpful, or cost-effective? Absolutely not.

I want to make sure that we have a force that is committed to doing things like abolishing police brutality and abolishing racial profiling and abolishing all the other aspects that it sounds we’re in the process of doing now, the no-knock warrants, and all this kind of stuff that should never have been in place in the first place. That actually means taking an internal look at the entire system. Being able to really do a true self audit of what aspects of the system do you actually need and have to have in place when it comes to creating a true mechanism that prompts and promotes safety, and security, and communities, and does it on an even basis? Because we do not have that right now.

Yeah, I think people get defunding mixed up with abolishment. I’m glad you broke it down like that. George Floyd cracked the race war open. We see so much happening in our country right now, nationwide protests, global calls for help. Do you see anything positive out of this? Do you think the world is finally going to get it, or when the pandemic ends and people go back to work, and all of the businesses start to open up and people start having their cocktail parties, and their day parties, and their mixers, is everything going to go back to being the same?

Listen, hope springs eternal. I hope and I pray. I really do think we actually have seen certain movements in the right direction. One thing that I’ve noticed is things that you’ve been saying and I’ve been saying for years. This is not exaggeration. These discrepancies aren’t hyperbole. We’re not making stuff up. They’re real. The sound of a police siren sounds different. The pitch is different depending on what community you’re in. One thing that I’ve seen is that actually there’s a relative level of positiveness that we’ve seen is not just our society, but the world at large. They get it now. We’re not having to justify that argument anymore in an important way.

The thing that I want people to understand, though, and I think we have to be very aggressive on, is if we just think that banning choke holds is the point, then we’re missing the point. The demand for justice is, yes, it’s about justice for George Floyd, and we need justice for his murder, it is about justice on demanding police accountability, but also, it’s economic justice.

Straight up.

It’s health justice. It’s environmental justice. It’s housing justice. It’s educational justice. We want justice. We want justice of all forms. I am hopeful. I’m hopeful that we can have a unified conversation about justice, of every single definition of the word justice. A takeaway from Mr. Floyd, the takeaway from his murder, is I want justice to be served. Justice doesn’t just mean for individuals. It means, how are we creating a system that actually creates pathways and opportunities for people who, frankly, the world is now awakening to the fact that there’s this level of injustice that exists for so many people?

Let’s talk about your new book “Five Days: The Reckoning of an American City.” It’s been five years since the death of Freddie Gray, who died as a result of injuries he received while in police custody. Since the death of Gray, Baltimore has continued to go viral for a number of crazy things. The Gun Trace Task Force, which was a group of rogue cops that robbed citizens and sold drugs.

In broad daylight.

Our mayor Catherine Pugh was caught up in a children’s book scandal that netted her over a half a million dollars. President Trump came our city, calling it rat-infested and attacking the late, great Elijah Cummings. You walk us right into this world in your book. Give us a snapshot of some of the things that were going into your mind while you were writing.

First I want to say how much I appreciate you and your voice throughout—not just everything that was happening five years ago, but also making sure that people don’t forget. It’s amazing. We’re watching this process right now taking place, and now it feels like society is acting like this is brand new. It’s not brand new. I now hear people sometimes say, where it’s like, “Wow, the timing of this book is really amazing.” Part of the horror of that is, name a time when this wasn’t appropriate.

Exactly.

One of the things that actually triggered me to be able to want to tell this was my own complicity in all this. I went to Freddie’s funeral and I remember looking around. First of all, it was one of the only funerals I ever been to in my life of, I’m at the funeral of someone who I never knew. Because it was more . . . I felt like a spectacle. Everybody was there. Everybody showed up. What was there, 2,500 people, you know.

Yeah, it was packed. I was up in there, and it was packed.

It was packed. I’m sitting there, and I actually didn’t even want to take the walk up to go to the casket because I didn’t feel like I earned that. I felt like that was part of the problem. You sit there and you’re looking around the room, and you’re wondering, how many of these people are actually willing to do what it’s actually going to take to make sure that this doesn’t happen anymore? The fact that when we’re looking up, we see the banner that says “Black Lives Matter.” Do people understand the inherent contradiction of all this? That we’re sitting there with a casket with “Black Lives Matter” being profiled up behind it?

What I then wanted to do is explore that period of time, that five-day period, starting off with the Saturday and ending off with the Wednesday, and really take it day by day. Look at it through the eyes of these eight different people, who all come from different strata, different perspective, different reasons why they’re there, different things that brought them to this, and be able to really ask some hard questions about, what is our level of complicity? Our societal level of complicity that these things keep happening, but people continue to act like it’s brand new?

You answer the biggest question in the book: Why this city? Why this reaction right now? To me, you answer it in the first couple of pages when you just break down the timeline of Freddie’s life. There are so many people in Baltimore and they all don’t have the same fate as Freddie, but at the same time, we’ve got the lead poisoning, the poor schools, the unequipped teachers who don’t really know how to handle a student like Freddie or recognize his or her talent. When people have that backstory, it becomes so easy to forget about them.

I’m telling you, D, and shout out to Chris Jackson, who’s my editor for this book, because that actually wasn’t in there initially. I just went right into the stories. Chris pushed back and was like, “Something’s missing. You’ve got to ground the reader in what we’re talking about.” We were going back and forth about what that is. Then he was like, “How about you just lay out a timeline of his life?”

For people who don’t know or forgot, tell us about Freddie Gray.

You bring up an important point, too, because people think that, “There was Freddie,” but we have to remember, in just the 24 months prior, there was Chris Brown, and there was Anthony Anderson, and there was Tyrone West. You saw how Freddie Gray wasn’t an anomaly. Freddie Gray was a continuation when you looked at what was happening within Baltimore. For the timeline on Freddie’s life, Freddie was born premature and underweight, him and his twin sister Fredericka. They were also both born addicted to heroin. Their mother has battled addiction for much of her life. She never made it to high school, and lived in poverty all of her life. She gives birth to Freddie and Fredericka. They’re in the hospital for a few months, just until the babies are able to gain enough weight that they can actually then leave the hospital.

When they leave the hospital, they move into a housing project over in North Carey Street, over in West Baltimore. That house, along with over 400 other homes, in 2009 is named in a civil lawsuit because of the endemic levels of lead that are inside that house. The CDC indicates that six microbes of lead in every deciliter of blood is enough to give a person cognitive damage for the rest of their life. Six. Freddie had 36. This was a person who was suffering from severe cognitive damage for much of his life. As you pointed out, he had been placed in special education courses and coursework throughout his entire academic career because of the lead poisoning. The last time that the Baltimore City Public School system had his recorded attendance was when he was in 10th grade, and he was 19 years old.

He’d watched his stepbrother killed just a year and a half before he died. This was a person who, when you look at Freddie’s life, he was born underweight, addicted to heroin, lead poisoned. By that time in his life, he’s 2 years old. What shot did Freddie have? What opportunity? When people say, “People should just work harder,” how hard would Freddie had to have worked in order to even have a shot?

You have to look at those five days in that context. You have to understand what happened in Baltimore in the context of the fact that we are still not even giving our kids a chance. When he had that final interaction with these six officers, the reality is Freddie could have died a hundred times before that. We had people saying, “Freddie was a thug.” What are you talking about? It’s important to ground people in exactly this dynamic as we’re having these conversations, both about his life, but then both about everything surrounding his death and also the aftermath in the entire city.

Yeah, before you jump out there and call this person a thug, talk about the failed War on Drugs, and how his 18 arrests almost led to no convictions. This is the War on Drugs. This is how we pad out that to make ourselves look like we’re tough on crime, when actually we have a system that just ruins lives over, and over, and over again. . . . I feel it. I know that my brother, my cousin, myself, any of us could have been in that situation . . . We’ve been thrown in back of the van like how Freddie was thrown in head first. A lot of people don’t know he died — it was a shallow diving accident. When he was thrown into the van, that’s how he sustained the injury. I’m looking at it and I’m angry.

But, at the same time, you have different people who might look at the situation differently. A person who lives in the suburbs, a person who was a police officer, a person who just happened to be hanging out, and their life was forever transformed by what happened after Freddie died. You do a great job at introducing us to this array of people who all come at it from a different angle. How did you choose those people?

Honestly, D, that was one of the more complex thing, because, as you know, Baltimore is a city of characters. You know what I mean?

Yeah.

You could go all over the place and find people that would fill in. But it really came down to, how was I going to select eight that in some ways encapsulated different aspects of the society? The process of elimination was actually one of the hardest things about it. We end up landing on being able to tell the stories of people like Tawanda Jones, a woman who has been protesting the death of her brother [Tyrone West] in police custody and is now marching right alongside the Gray family, and is proud of the fact that Baltimore’s standing up. But, at the same time, has these feelings of, “Where was this when my brother was killed?” Every Wednesday she protests, and still does to this day.

West Wednesdays. Every Wednesday.

She does not stop. It’s amazing. Being able to add in a story, actually, like a Marc Partee, a major in the Baltimore police force, who comes up from West Baltimore. I’ll never forget this conversation, when he said, “No, I don’t think that any of my fellow officers, none of them woke up that morning with homicide in their minds.” He said, “But I understand, for the kids in West Baltimore, why they don’t believe me.” I will never forget when he said that.

That’s a powerful moment.

Get the perspective of Greg Butler, a former basketball star in Baltimore, who escaped death on so many different occasions and now gets a scholarship to college, and is going to go play basketball in college only to find out, because of a mess up within the Baltimore city system of transmission of grades, that he loses his scholarship. Now he was like, “I thought I had a pathway. I thought I had the thing that I needed in order to get out.” I don’t want to give it away to the readers, but I know you remember the Dawson family and his connection to the Dawson family. It happened in Baltimore. It’s like, here’s a guy who was doing everything right, and, to no fault of his own, because of a system glitch loses his scholarship. Now he’s coming out, and he goes from basketball star to protester. He’s protesting more than just Freddie; he’s processing the entire system that’s been created.

John Angelos, the son of the owner of the Baltimore Orioles, who is having to make one of the final decisions about, do they play a game with no fans? He says, “Yes, because I want the world to see it.” Anthony Williams, the general manager of Shake & Bake. I first went to Shake & Bake when I was 13 years old. He’s a small business owner and a community leader. Throughout this whole process, he’s trying to understand, how do people not see? Even if you just look at Pennsylvania Avenue, and what’s happened to Pennsylvania Avenue over the past 30 years, how do people not understand that we saw this coming? We saw this coming. I wanted to take the readers on this journey through these eight very different people, through these eight very different lenses, but how the power of this moment was actually this crash between all of them. It’s a reminder to all of us about just how thin that line is between our life and somebody else’s life, particularly when tragedy and crisis becomes the glue that actually brings folks together.

When I write books and articles and when I do research, I always learn something about myself. I always learn something about the area, the neighborhood, or the city that I’m researching. What did you learn about yourself by doing this? Did you learn anything new about Baltimore?

That’s a really good question. The thing that I really learned about myself is it really did add a level of history and humility that I don’t think I fully embraced before. I think about my own work, where every one of these issues that we talk about within this story gets profile, and highlighted, and funded, and built out through the organization. I’m really proud of the work that we’ve been able to do. How do you increase proximity? We’re now investing in Baltimore.

You realize, man, you cannot understand where we are now without understanding history and trauma. You cannot do it unless you’re fully willing to embrace the intentionality of the separation that exists. I think it’s one thing to come up in it like we came up in it, and it’s another thing to actually become a student of it. I think this process forced me to become a student of it. To not just understand it inherently, because, yes, we just know it because we know it. But actually say, “No,” actually dig into redlining. Actually dig into discriminatory housing. Actually dig into discriminatory lending policies. Actually dig into the fact that the GI Bill was used to build up an entire middle class despite the fact that it excluded Black people.

And we fought in the war.

You know what I’m saying? This process forced me to become a student of it, where it added a real level of not just intensity to try to do something about it, but a humility about the fact that so much of what we’re doing right now, unless you can dig into that stuff, it’s elementary, man. It’s significantly around edges.

I find it troubling, just living in Baltimore, being from Baltimore, and being in some of the circles that I’m in now – I talk to a lot of politicians, and I talk to a whole lot of people who have power to change some of these things, or to at least start the conversations about change in the places where the conversations need to be had. I’m just in awe at the amount of people who don’t even know the history of this city. They don’t know about the GI Bill. They don’t know how the suburbs were built. They don’t know about redlining. They don’t know about blockbusting. They don’t know about anything. I just wonder, why get into public service? I know you know all of this stuff, and you studied, and you’re brilliant, and you’ve had success. How do you gauge success? Because we all know that one person or one organization is not going to flip hundreds of years of problems. But, at the same time, there’s so many wins on your journey.

No, I love that question because, honestly, D, it’s one of the things that I still very much wrestle with. When I talk about complicity, it is actually that. I think it’s beautiful for the fact that people are like, “Listen, will you come spend time and talk to us about this issue, and help us to understand?” It’s beautiful when they’re like, “Listen, D, can you come and write a book or tell a story that helps to illuminate?” That’s beautiful, and it’s important because it then means that not only is their level of appreciation of us as individuals, it’s appreciation of the story we have to tell.

At the same time, there is an exceptionalism of it that’s really hard and disturbing. One of the beautiful things I try to find in my situation is, we can go in any environment and be comfortable. You can seriously go down and spend time hanging out on MLK, and then the next day go spend time hanging out in the Hamptons, or hanging out down in Washington. You know what I’m saying? You’re agile. You are fully accepted and incorporated into all these various environments, myself the same way. But, there is a level of exceptionalism about that which does become very frustrating. You want the celebration to not be seen as a pacification. You don’t want the celebration to be seen as, “No, look, I get it. I’m enlightened. See? I’m having Wes come and talk to my group.” Or, “See? Oh, no, I get it. I’m enlightened. I’m ordering these books for . . . ” No. That can’t be enough.

I think it’s beautiful that people actually want to engage in this. It’s beautiful that people find not just a level of time, but a level of appreciation in the work that you do. But, if you want to hear my opinions on it, be ready for my opinions on it. If you want to hear what I think, be ready to hear what I think. It’s not a enough to indict individuals; we have to indict systems. Those systems oftentimes exist because people have benefited from the systems.

It’s one of the frustrating things. Oftentimes when we think about this idea of racism, people think racism is an individual act. They’re just like, “I’m not racist.” Or, “I don’t say the N-word, therefore I’m not racist.” It’s like, no, you have to get out of the idea of the racism as an act. Racism is a system. It’s a system that allows a Black person with a college degree to earn less than a white high school dropout. That is a fact. That is a statistical fact, and that is a system. It’s a system that allows Black Americans to die at twice the rate from COVID-19 as white Americans. It’s a system that makes it 42% more likely for a Black woman to die of breast cancer than a white woman who also has breast cancer. I think, when we think about this work, and again, you bring up a really important question, because I know it’s something I still very much wrestle with. It’s this idea that . . . this is a system that has been built and reinforced for 400 years and we’re having this conversation today, D, on Juneteenth. Part of the goal with “Five Days,” is if you really want to know about history and how this stuff goes in context, read this, because you’ll walk away saying, hopefully, “I get it.”

“Five Days” is a start for readers. After they read the book, they have to follow up.

Then the work begins. What I tell people is, “What does it mean to be anti-racist?” People get scared about this term. There’s nothing to be scared about. What an anti-racist is, it’s both identifying these realities and then being willing to do something about it.