Journalistic "objectivity" — as enforced by editors in our top newsrooms — encourages reporters to engage in credulous, both-sides stenography instead of calling out liars and racists.

It discourages reporters from telling the hard truths — depriving readers "of plainly stated facts" that "could expose reporters to accusations of partiality or imbalance," as the Black journalist Wesley Lowery wrote recently wrote in a blistering New York Times op-ed.

Journalistic objectivity, in theory, is about observation and verification. But in its current newsroom practice, it is more about overly esteeming the status quo and casting a censorious white, center-right, male gaze on anything remotely controversial.

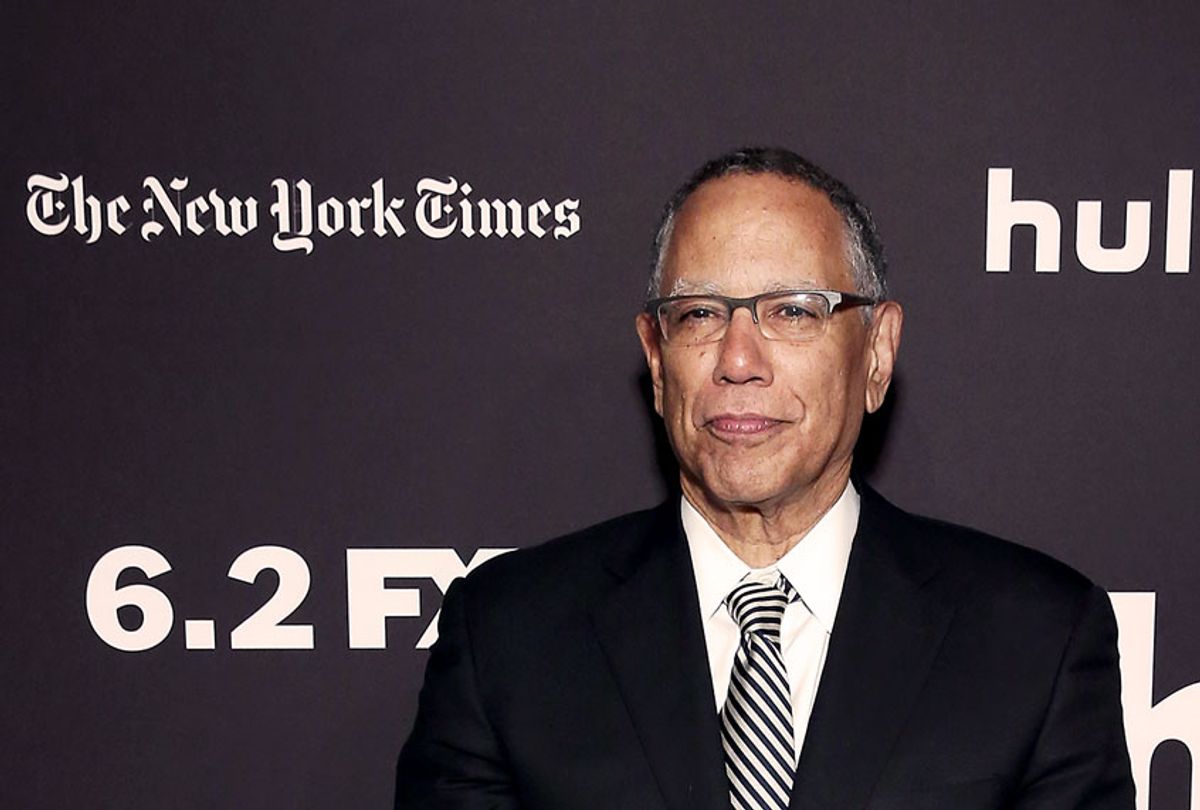

Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the New York Times, considers it a "core value" of his newsroom that he intends to guard as long as he remains in charge.

In a long and probing interview with Longform.org co-founder Max Linsky on the site's podcast last week, Baquet responded to Lowery's op-ed and to the unprecedented open revolt among Black Times staffers and others after the publication of an inflammatory and sloppy op-ed by Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas calling for the military to forcibly subdue Black Lives Matter protests.

Baquet said he is open to increasing newsroom diversity and inclusion.

But when it comes to Lowery's demand for greater "moral clarity" — so that editors and reporters, for instance, "stop doing things like reflexively hiding behind euphemisms that obfuscate the truth" — Baquet was totally dismissive.

"I have to protect the place. I have to make it better, but also sometimes resist the things that they want to change because I think those things are important to the core," he said.

Baquet knew Linsky was going to ask about Lowery's critique of faux objectivity, so he came prepared with his own definition: "To me the goal of a news story is to capture the news to the fullest, with as much precision as possible, every current viewpoint, personality, underlying motivation, and relevant piece of content," Baquet said.

Reporters, he said, should go into every story with an open mind — regardless of what they may already know to be true: "Open to what you hear, empathetic to what you hear."

He also came prepared with a metaphor. "For me," Baquet said, "the objective reporter — but let me not use that word because I don't love it, let me use 'the independent and fair reporter' — … he gets on an airplane to pursue a story with an empty notebook, believing that he or she doesn't fully know what the story is, and is going to be open to what they hear."

But think about that metaphor for a bit.

First of all, it's appropriately anachronistic. Sending a reporter to pursue a story someplace entirely new to them was a rare occurrence even before COVID-19.

When asked for an example of what he meant, Baquet provided a ridiculous one: "The guy who gets on a plane to do a story about the Minneapolis mayor's race, maybe in the bottom of his heart doesn't like Minneapolis."

But more to the point, when it comes to covering Washington and domestic politics – easily the most contentious coverage areas for the Times — there's no way reporters can or should embark anew and empty-headed every time they cover a story.

Ironically, it would actually be great if American reporters could cover Washington as if they were just-off-the-plane foreign correspondents — without undue deference to authority and with no allegiance to stifling local conventions. (And that's something I think some news organizations, like the Los Angeles Times, should aspire to.)

But New York Times reporters, like so many other elite media players, are steeped in Washington culture. So the question is whether reporters should use their brains to interpret what they see in the context of what they know to be true and what they have themselves written before or whether they should, as Baquet evidently requires, be diligent note-takers in a brand-new notebook, "empathetic" to "every current viewpoint."

You can see Baquet's dictum playing out almost daily in the Times, most obviously in articles by his star reporters Peter Baker and Maggie Haberman, when they and others write about such things as Trump "struggling to unify a nation on edge" or express shock that the two parties can't even agree on the facts.

Sucker move

Nobody and nothing has ever exposed the failure of modern "objective" journalism like Donald Trump, a pathological liar stoking racism and conspiracy theories during a pandemic, supported by a party unmoored from reality.

But to Baquet, that's no reason to change.

In an interview he did on the Times's own podcast in January, he defended what he called "sophisticated true objectivity" — which he distinguished from "labeling and cheap analysis." You don't call it a lie, he said. "Let somebody else call it a lie."

During the Longform interview, when he was asked what demands from his staff he considers a threat to core New York Times values, Baquet was quick to answer — defensively.

"I think we're very aggressive with covering Donald Trump. I think we're as aggressive as anybody, if not more. I think some of them would like us to be even more aggressive," he said.

Baquet casts that demand as some sort of existential threat to the Times that he, nearly alone, has to guard against:

Here's the difference between me as the editor of the paper and everybody else, I guess, except maybe the publisher: I have to juggle two things, right? I have to figure out how to cover this president who is an anomaly in modern American politics. And I got to come out the other side with the core stuff intact.

I can't throw everything to the side and say, this guy's different, we're just going to be completely different. Because I got to wake up the day after he's not president, or else my successor has to wake the day he's not president, thinking we're still the New York Times.

What does he even mean by that? What is this "everything" that he would he have to "throw to the side" that would make it impossible to cover the next president in Timesian fashion? I'm not really sure. Heck, I'm not even sure Baquet really knows what he means.

Is he saying that's why the Times can't bring itself to call Trump racist? I don't see how calling Trump racist would make it hard to cover the next president, racist or not. The rule seems simple to me: You hold presidents to consistent standards, and different presidents meet them or not. That's not your problem, that's theirs.

Here, in the name of some sort of consistency, Baquet is actually changing the standard between presidents, which is a disservice to his readers.

If Baquet views Trump is an "anomaly" that the Times somehow needs to get beyond with its values intact, well then maybe it's no wonder his reporters so consistently fail to convey how dangerously aberrational Trump is.

My best guess is that what Baquet really means is that he's not willing to reconsider any of the timeworn journalistic algorithms Times political reporters use to cover Washington — even though those algorithms were built for presidents whose announcements constitute news rather than misinformation and for two political parties that have comparable relationships to reality.

Several times during the interview, Baquet talked about the importance of distinguishing between "what is truly tradition and core and what's merely habit." He explained: "You've got to say, 'Here's what's not going to change. This is core. This is who we are.' Everything else is sort of up for grabs."

But the continued use of those algorithms is arguably the key to the implosion of the Times's political journalism under Trump. And those algorithms do not represent any kind of core journalistic value. They are, precisely, habits — habits doing terrible damage to the core. So he's got it entirely backwards.

Linsky tried to draw Baquet out on this issue. Here's a wonderful exchange:

Linsky: But getting back to Trump and how you cover him in a way that stays core. Help me understand why calling him a racist in the pages of the New York Times is not the most direct and accurate way to describe him.

Baquet: So I have — I have very complicated feelings about this. First off, we have said he uses racist language. We said it in the last two days.

Linsky: But it's not always that the phrase is, "he used racist language." Sometimes the phrases are more opaque, less direct, more euphemistic —

Baquet: Can you list anywhere where we were a little too opaque? Well, I'll admit that.

Linsky: Does that come from you?

Baquet: I think it came from the institution. We're not used to having presidents of the United States who say the things he says, right? So, you know, I can make the case that in the very beginning, we were a little opaque. Less opaque in the last year or two of his presidency, far less opaque. Look, we all have to get used to this president, right?

Linsky: We do?

Baquet: Hmm?

Linsky: We do?

Baquet: (Laughs) We have to get used to? Well, if you cover him every day and you're writing half a dozen stories about him, you have to, I don't know if you have to get used to it. You have to develop a system. You know, he defies our systems.

So they have a system. They recognize that Trump defies it. But they continue to use it anyway, to preserve it for the next president?

It makes no sense. But Baquet is resolute.

"I know what I believe we have to hold on to, that core of who we are, which is independence and some empathy and balance," he said toward the conclusion of the interview. "I hate the word, but I'll use it: some version of objectivity."

Shares