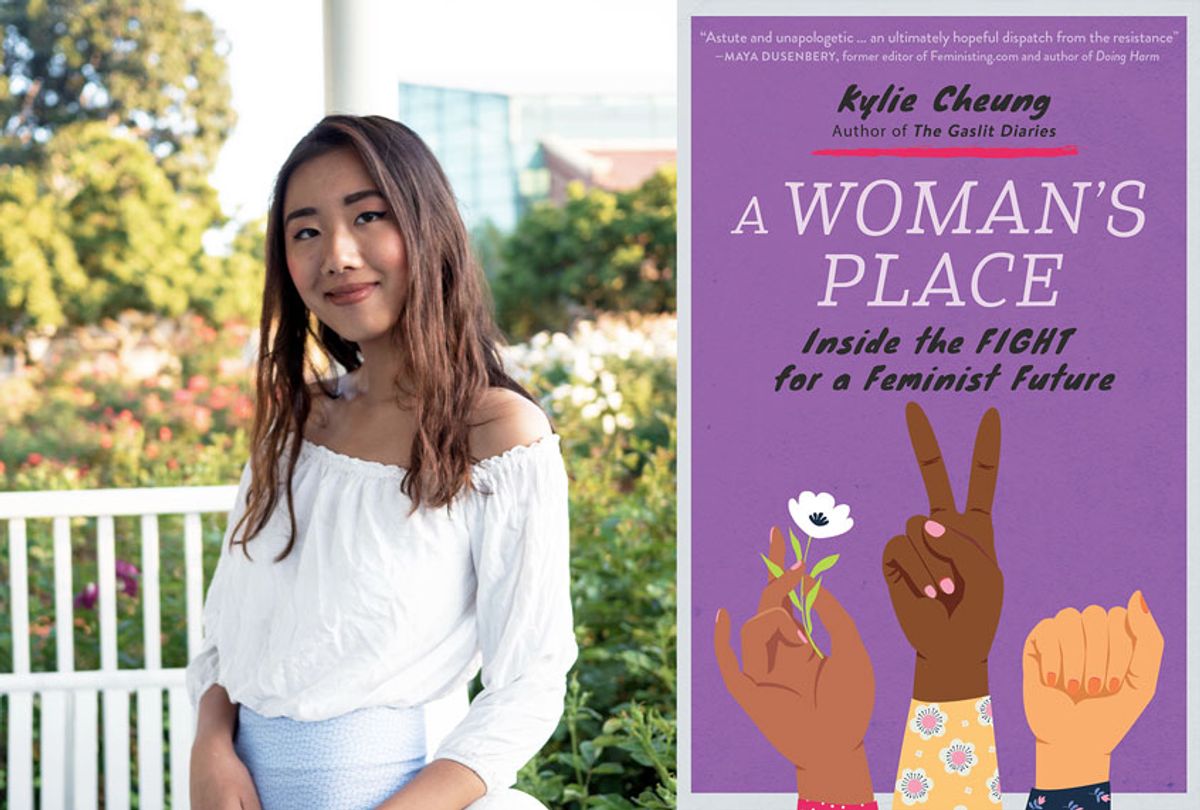

The past few years have largely felt like a setback for the cause of feminism, starting with the fact that Donald Trump, who is as unfit for the presidency as humanly possible, managed to beat the eminently qualified Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. But young author Kylie Cheung wants to help pave a path forward. In her new book, "A Woman's Place: Inside the Fight for a Feminist Future," Cheung lays out a vision for a feminism that can learn from those setbacks and use that experience to push for a better future.

Salon spoke with Cheung about being a young feminist in such perilous times and what it means to have a feminism that keeps going in the face of even some of the ugliest defeats. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You're a young author trying to get publicity for your book during a once in a lifetime economic and social crisis, or at least I hope it's just once in our lifetime. How are things working out for you? How is trying to promote the book going?

Actually, right now, I think a lot of the messages in the book have been more timely than ever. As we kind of live in this time where, I'd say even before 2016 there were a lot of really existential fights for women and people of color that were raging on. And then the 2016 election really seemed to bring all of that to the forefront, and then really ever since then, whether through these different elections, through fighting Kavanaugh's appointment, through fighting so many different cruel policies. I think the truth is that there's definitely going to be a lot of really painful outcomes.

The sole message of the book is that no single outcome really ends this fight of the feminist movement. The message of this book is that there's no way to really lose other than giving up. I think if anything, it's been more timely than ever.

You were in your first year of college when the 2016 election went down, which is certainly a shocking event at any age, but especially at such a young age. How did that election influence your views of politics and feminism?

It was definitely a big wake-up call. I was expecting Hillary Clinton to win, and her loss and my being blindsided by that really woke me to a lot of my own privileges that had blinded me to a lot of the realities within the country.

I definitely think in terms of the Trump administration being a big wake-up call. It raised my consciousness about a lot of the problems that were existing even before his election.

For example, ever since Roe v. Wade in 1973, there had been around 1,200 or so anti-abortion laws that had passed across the country since. Nearly 90% of U.S. counties are without abortion providers.

But I think about the consciousness-raising that it did for me and for a lot of young people, a lot of young women, to become aware of our power. And not just our power but the crucial need for us to be at the forefront of this fight, in particular, was definitely a big wake-up call.

You have a chapter titled "The Right to Bear Anger," which explores how men have a lot more social permission to be angry than women. Even, and I'd say especially, when women have more right to be angry. The Brett Kavanaugh hearings, you argue, especially highlight how this is true. How is that so?

I definitely think the Kavanaugh hearings were just such a salient example of this, where if you look at his testimony juxtaposed with Dr. Ford, you could just see that, as a survivor of assault, she has managed to come with so much grace and so much dignity. And he, just in terms of being faced with some level of accountability, some level of being confronted about his own actions, there was just so much rage there. And I think the foundations of that rage were really just this male entitlement and this shock at being held in any way, even just a little bit accountable.

That is such a striking example of this disparity, in terms of who is given social permission to wield anger and how that anger is responded to in society.

Going back to the 2016 election, when you look at the anger of Trump supporters, that was given so much validation and that was so, I think, deeply legitimized by a lot of mainstream media. They would profile different Trump supporters but would never really profile, say, the many people of color, the women, the undocumented people, all of these different marginalized groups and what the election meant to them, where they had every right to be angry, to be infuriated by the system that's so built against them.

There definitely are legitimate reasons for anger among different communities that have been left behind by our political system, by our economy. For people who are marginalized on the basis of their identity, there's even more reason to be angry. And yet the only anger, it seems, that we are willing to shine a light on, be sympathetic to, in terms of what we are asked to pay attention to by a lot of mainstream media, would be white male Trump supporters in rural parts of the country.

When I was a younger writer starting out myself, in the '00s, feminist bloggers like me were trying to start this conversation around sexual consent and "yes means yes" and all of that stuff. We got laughed at and told it was ridiculous to expect people, especially young people, to embrace the idea of enthusiastic consent, this idea that everyone in a sexual encounter should actively want to be there. So as a bonafide young person, I want to ask you, how does your generation actually think about these issues?

It's really interesting, I think, to be this age at this time, to have been on a college campus as #MeToo was emerging. Even among a lot of men who would like to think of themselves as allies, and a lot of people who I think might have good intentions, there was just so much fear-mongering. This fear of, "Oh, now I have to think about how I might be making someone else feel, when I never had to do that before."

This fear is not equitable to the fear of being raped and killed, which is something that young women, all women really, have had to live with all of our lives, and how that's shaped so many different aspects of our everyday lives. Just in terms of walking alone at night!

For so long we've given men a pass to see themselves as not having a role in this when, in most cases, men are the perpetrators of sexual violence. They have the greatest role in this issue.

It's really a time to call on young men to not just implicitly support women, but to explicitly and actively talk about rape culture and predatory behaviors with male friends. And for reporters to not just be asking women about sexual violence, but ask everyone about that. And to dispel this myth that the onus should fall solely on women to fight this issue when we are not the sources of it.

Trump himself said that this is such a "scary time for young men." One of the things about that comment, and all the ways various conservatives have kind of echoed that idea, is really about reversing reality. In reality, men present a real danger to women. Most sexual predators are male, and victims come in all genders, but most of them are still female. It's about reversing who's the victim and the victimizer. Why do you think this myth that men are the victims of these false accusations and women are the real predators has such a hold on people?

This reminds me of that famous quote about how when you're accustomed to privilege, equality seems like oppression.

#MeToo was such a good opportunity for a lot of media outlets to dig deeper into how this movement might have made even some women feel even just a little bit safer in their workplaces, or just a little bit more visible. Instead, we saw so many headlines about all of these different male celebrities who now felt afraid, or these studies about how male supervisors now felt scared to spend one-on-one time with female employees.

Just all of these different ways that the male perspective and male comfort were so prioritized in all of this, I think really speaks to how there's always the sense that people who are in positions of privilege, if there's even a little bit of a shift, that will be seen as just so oppressive toward them instead of celebrated as shifting power dynamics to favor people who have always been marginalized and always had to live in fear.

The Democratic primary started off in this promising way, with a lot of candidates of color and women and even a gay candidate. By the end, however, it was whittled down to two straight white men who are both older even than the Baby Boomers. And then it was just down to Joe Biden. So what happened here? Should we just give up all hope of a Democratic leadership that looks more like Democratic voters?

A deeply disappointing and deeply frustrating process. Even talking about sexism becomes such a liability for female politicians who are seen as weaponizing sexism, or seen as "playing the gender card."

It really just goes back to the fact that there's never going to be a singular outcome that will end this fight. For better or for worse. I think even if we had nominated a candidate who's more representative of the shifting demographics, the work would obviously still need to continue. I think that a core message I try to speak out against in the book is that, even in these losses that are very difficult and painful, the organizing that we did, the consciousness and the awareness that we raised for the importance of having more representative leadership for our party, that lays the groundwork for winning future fights.

Shares