A lawsuit filed by Breonna Taylor's family alleges that her police killing was linked to a redevelopment effort in the West End of Louisville (even though she did not live there). Although city officials have denied this, policing experts say departments around the country have targeted Black people in the pursuit of gentrification for years.

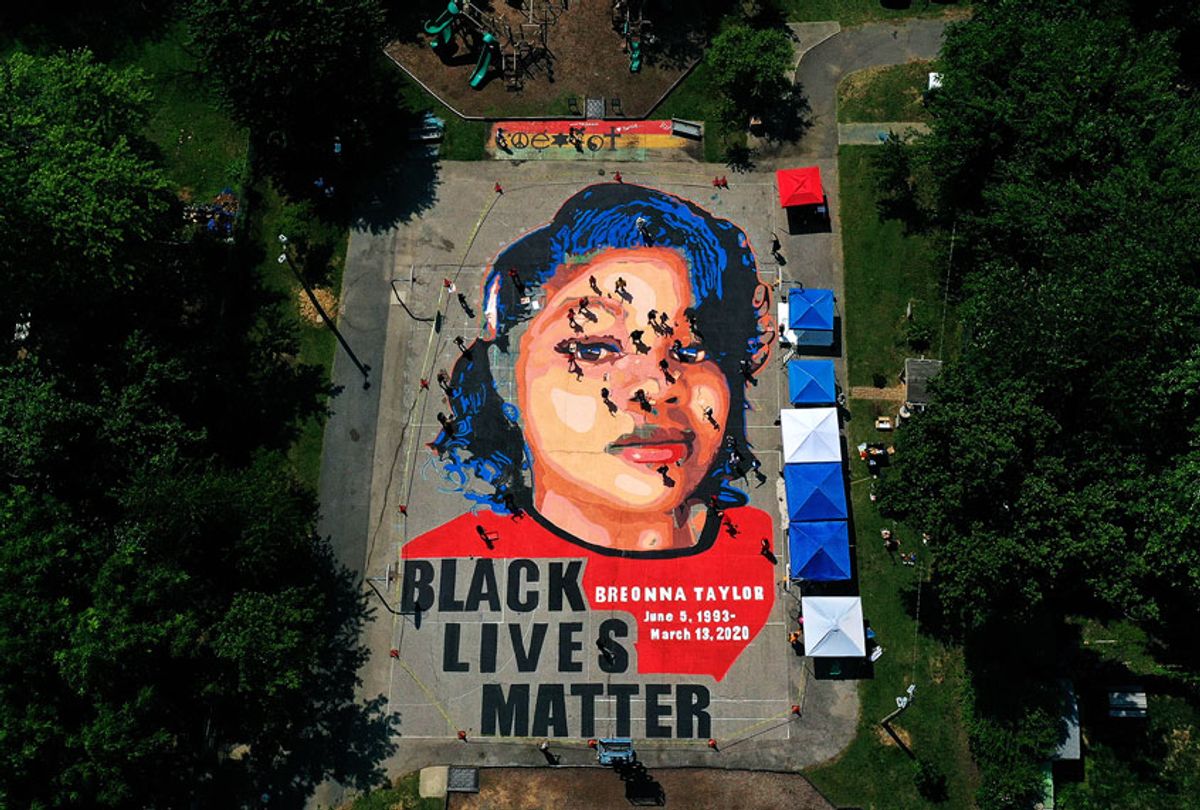

Taylor, a Black emergency room technician, was repeatedly shot in her apartment in Louisville's South End and left to die on the floor by police executing a no-knock search warrant in the early hours of March 13. A lawsuit filed by Taylor's family alleges that the operation, which targeted Taylor's former boyfriend for alleged drug offenses committed in a different part of town, was part of an effort to clear residents from the area where he lived, in the West End, which was slated for demolition to make way for a multi-million-dollar development project.

The city of Louisville has categorically denied the allegation, calling it "outrageous" and "without foundation or supporting facts." But such a connection between gentrification programs and brutal police tactics "wouldn't be uncommon," said Brenden Beck, a professor at the University of Colorado Denver who studies the link between gentrification and policing.

"Cities often use police to pursue redevelopment ends and gentrification often coincides with increased policing," he said in an interview. "So if this were the case in Louisville, it would hardly be unique. So I wasn't surprised [by the lawsuit], but of course ... it's a shame that cities are still using arrest tactics, especially for… drug crimes to pursue redevelopment," especially in a case that apparently cost an innocent person her life.

The 2014 killing of Eric Garner by a New York police officer was a "classic example" of a Black person targeted by police in a gentrifying neighborhood, in this case on Staten Island — the most suburban and least diverse borough of New York City —said Paul Butler, a former Justice Department prosecutor. Garner was known in the community as a "peacemaker" but police targeted him for selling loose cigarettes, Butler said.

"It's hard to believe that anybody would really care that much about somebody selling a tobacco cigarette on the street," he said. "So why in the world would somebody be arrested for that? It's just a question, like any misdemeanor, of police resources. And the reason they want to focus on 'loosie' cigarettes is to clean up that park. To send the message that this park belongs to us and not to the people who've been hanging out here for a long time."

Beck published a study earlier this year showing that police in New York made more low-level arrests in neighborhoods experiencing real estate investment, suggesting what he called "development-directed policing."

"Development-directed policing is the use of police to pursue redevelopment, urban renewal plans," he told Salon, citing the famous example of how police cleared out New York's Times Square, once filled with porn theaters, sex workers and drug dealers, because the city wanted the area to be "more economically profitable."

But the practice is not limited to high-profile areas. Beck's study found that residential neighborhoods that "saw an increase in real estate investment saw an increase in misdemeanor arrests" and what Beck terms "proactive" arrests.

Proactive arrests mean that police increasingly target low-level crimes that are rarely reported to 911, he said. It's an "increasingly popular approach that police are taking now that broken windows [policing] has been discredited and the drug war has been discredited," Beck added.

Police "hope these sort of proactive arrests will deter more serious, violent crime," he said. "But as with broken windows, there's not a lot of evidence to support that right now. The harsh enforcement of misdemeanors doesn't deter crime, it doesn't decrease violent crime."

Beck authored an earlier study with Adam Goldstein, a sociology professor at Princeton, which found that cities that "relied more on their housing markets for economic growth in the lead up to [the 2008 housing crash] spent more on police."

"We suspect that that was an attempt for cities to protect housing values," he said. "We know crime rates and housing prices are very closely related. Mayors, city council members, and police chiefs often talk about the importance of keeping crime low so that they can keep housing prices high." In a study of 170 cities, Beck said, they found "development-directed policing" occurring at both the level of individual neighborhoods and citywide.

The rise in these "quality of life" arrests has also been highly visible in Washington, D.C., said Butler, who is now a professor at Georgetown University.

"When communities are becoming gentrified, which in the United States usually means that they're changing from majority people of color to majority white, law enforcement steps up and police violence or police abuse against young African-American and Latinx people often steps up as well," he said. "If the police wanted to go and arrest a thousand people today for misdemeanors they could — there's an unlimited number of people who are offenders — so the focus of police officers on misdemeanor arrests goes up in gentrified communities." But not, he added, "for the gentrifiers."

Once a neighborhood is gentrified, the number of police calls generally increases. An analysis by researcher Harold Stolper published by the Community Service Society showed that the number of "quality of life" calls referred to police in New York increased substantially in gentrifying neighborhoods and were disproportionately aimed at people of color.

"As a neighborhood gentrifies, you have a new and growing group of affluent and predominantly white neighbors living in longstanding communities with different norms and a different relationship to the police," said Stolper, now a lecturer at Columbia University. "Black and brown communities are historically overpoliced in aggressive ways that can violently disrupt communities, whereas many white people are accustomed to viewing the police as an ally to enable their own notions of community and personal preferences. This creates an environment where a relatively small but growing number of new residents feel they can weaponize the police to uphold their own norms. The resulting disruption of community is its own form of violence against communities of color with all sorts of consequences that unfold over time."

Butler, who is Black and saw his prosecutorial career end when he was arrested over false allegations by a neighbor, said in his experience that Black residents often welcome new middle-class white residents because they are seen as bringing "better government services to that community." But ultimately, the experience of Black men in gentrifying neighborhoods is often akin to "being colonized," he said.

"I think the colonizer metaphor is apt. And that then the experience becomes: These aren't people who want to share, these are people who want to take over," he said. "These are people who want to kick us out, and the police are an integral part of being kicked out."

Butler said that even as a former prosecutor he was "shocked" by studies that show white people feel comfortable around police.

"The idea that I would feel safe around police is almost like a fantasy. It's almost like this utopian ideal that could never happen," he said. "I'm like a middle-income guy … but even with all of my privilege, I never felt safe around police. And even in the instances in which I'd have to call the police, you just never know what's going to happen."

This increase in low-level policing has also been linked to a rise in police abuses.

"If you're ticketing more people or patrolling more often, you're stopping more people to ask questions on the street," Robert Sampson, a professor at Harvard, told The Atlantic. "Now, that's different than pulling a gun and shooting someone, or beating someone up, but the more stop-and-frisks and the more interactions you have, then probabilistically, you're increasing the risk for police brutality. So it's sort of a sequence or cycle."

As cities become whiter, so do juries. Research shows that all-white jury pools are significantly more likely to convict Black defendants than white ones.

"Jurors often have different life experiences based on their race. And so if the defense is 'the police lied' or 'the police planted evidence,' that's something that an African American or a Latino juror might well believe or find credible," Butler told The Atlantic. "A white person might find that hard to believe based on that person's experience with the police."

The insidious nature of gentrification policing makes it difficult to address in the current debate over police reform. Every expert interviewed for this article agreed that "defunding" the police, or to be more precise shifting resources from police departments to social services, is an appropriate way to address the underlying racism evident in modern policing.

"Of course it's possible for any society to not target certain communities for heavy-handed, over-policing, but not with the current policing infrastructure we have in place in most cities," Stolper said. "I think the choice to focus on 'police reform' is not unrelated to gaps in the data that helps shape these policy discussions — when the far-reaching consequences of our police systems are poorly understood by people in power, it's easier to call for incremental reforms rather than wholesale changes and defunding.

"But listening to the lived experiences of people of color, especially Black Americans in our most over-policed cities, is an even better way to frame the policy discussions that we need to have right now."

Beck agreed. "Police should never be used as the tip of the spear of redevelopment, so I think that's an easy policy change that mayors and city councils could make tomorrow," he said. "But defunding the police is a great way to ensure that police are focusing on violent crime and not on these sorts of low-level arrests that perpetuate harm. Redirecting that spending towards housing programs, community development initiatives and poverty alleviation programs can really address the causes of crime. It's going to be a lot more fruitful for cities."

Butler said he was heartened by how many white people have joined protests over the killings of Taylor and other Black people and are calling to address the "larger issues around white supremacy and the failure of this country to deal with the consequences of years of slavery and discrimination against Black people."

"What's important about this moment is that white people are taking responsibility for racial justice in a way that we haven't seen before," he said. "So if you go to many of the protests, many of the demonstrators are white, which I think is great. To the extent that white folks are now recognizing their role in perpetrating white supremacy and the ways that they benefit from it, that could also have important consequences for more effective public safety."

Shares