Every generation of activist has its own accompanying insult. Leftists in the past might have been slandered as "petty bourgeois" or "revisionists"; these days, calling someone a "neoliberal" is fighting words. More recently, the accompanying charge is likely to be "class reductionist."

That accusation reemerged recently when the Philadelphia chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) — the largest socialist organization in the country, which has been growing rapidly for the past few years and was a major organizing force for the Bernie Sanders campaign — issued a statement on the murder of George Floyd. As protests against police violence were spreading across the nation with dizzying speed, the Philly DSA said: "We are outraged at George Floyd's murder at the hands of the Minneapolis police. Floyd's killing and similar acts of violence stem from the brutalities and inequalities of U.S. society."

The statement went on to explain the expansion of policing in terms of the decline in "good-paying jobs and social services" in the United States, and made a strong claim about its own importance: "As socialists, we are also uniquely positioned to expose the economic dimensions of these instances of state violence and to push for demands that address their underlying causes." It concluded that the reigning demands for defunding the police were insufficient, and that achieving "racial and economic justice" meant "targeting the foundations of inequality" and creating "a more just society for all working people."

To be fair, this statement, which was very brief, referred to real social problems and proposed some constructive solutions to them. It nevertheless immediately provoked a flurry of discontent among activists in DSA and the online commentariat. It wasn't so much the content itself that many took issue with, but the fact that the statement appeared out of touch with what was happening on the ground.

For the protesters who had flooded the streets, racism was an obvious and fundamental cause of Floyd's murder, and it was deeply embedded in the structure and practices of the U.S. police. Referring this problem to economic inequality, which socialists were supposedly "uniquely positioned to explain" — despite the fact that they had been totally taken by surprise by the wave of protests — seemed oblivious at best, and condescending at worst.

The Philly DSA statement also didn't appear to actually take a position on the protests themselves, which was jarring to those who saw the burgeoning movement as a promising political development in the forbidding context of the pandemic. On the basis of firsthand observation, I can attest that while some elements of the protests included liberal elites and nonprofit organizations which sought reconciliation with a more diverse ruling order, they also included a broad range of working-class youth who took up the slogan "Black Lives Matter" while targeting symbols of economic inequality — like banks, chain stores, and luxury boutiques — without guidance from pre-existing organizations.

Three days later Philly DSA posted an update, describing its initial statement as "a mistake that we deeply regret," since it "did not sufficiently address the disproportionate impact of police violence on people of color, specifically Black Americans, and the significant anti-racist character of the protests." But the charge had stuck.

The label "class reductionist" is frequently thrown around on the left today, but as was once true of the word "hipster," it doesn't appear to be a label anyone willingly accepts. In fact, Adolph Reed, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the classic study of post-segregation Black politics "Stirrings in the Jug," has argued that class reductionism is nothing more than a myth.

What is class reductionism? The term is somewhat self-explanatory: it suggests a perspective which reduces all forms of social inequality to class. Concretely, this means that class reductionism is both a method (of analyzing everything in terms of class) and a program (proposing policies related only to class).

Some people — especially those who spend their entire political lives on the internet — proudly embrace the label, insisting that reducing everything to class is reasonable and desirable. However, the more serious people involved in these debates argue that class reductionism isn't an accurate description of their perspective or anyone else's. This is why Reed describes the whole category as a "myth." It's a myth in the sense that it's a distortion of reality, but also in the sense that it's a story we tell ourselves that makes certain aspects of our social and political lives seem natural.

Along these lines, when Reed argues that class reductionism is a myth, he means that no meaningful political tendency actually thinks that all social inequalities are reducible to class or that class-based reforms will solve every problem. (The extremely online people who do claim to be class reductionists apparently don't count.) Reed also presents an explanation of why people believe in the myth — why they make this accusation, and whose interests the myth serves. All these steps make the argument somewhat complicated and convoluted, but it's the most sophisticated response to the charge of class reductionism. So we'll try to untangle it and reconstruct the strongest version of the argument, to assess what's convincing about it and what isn't.

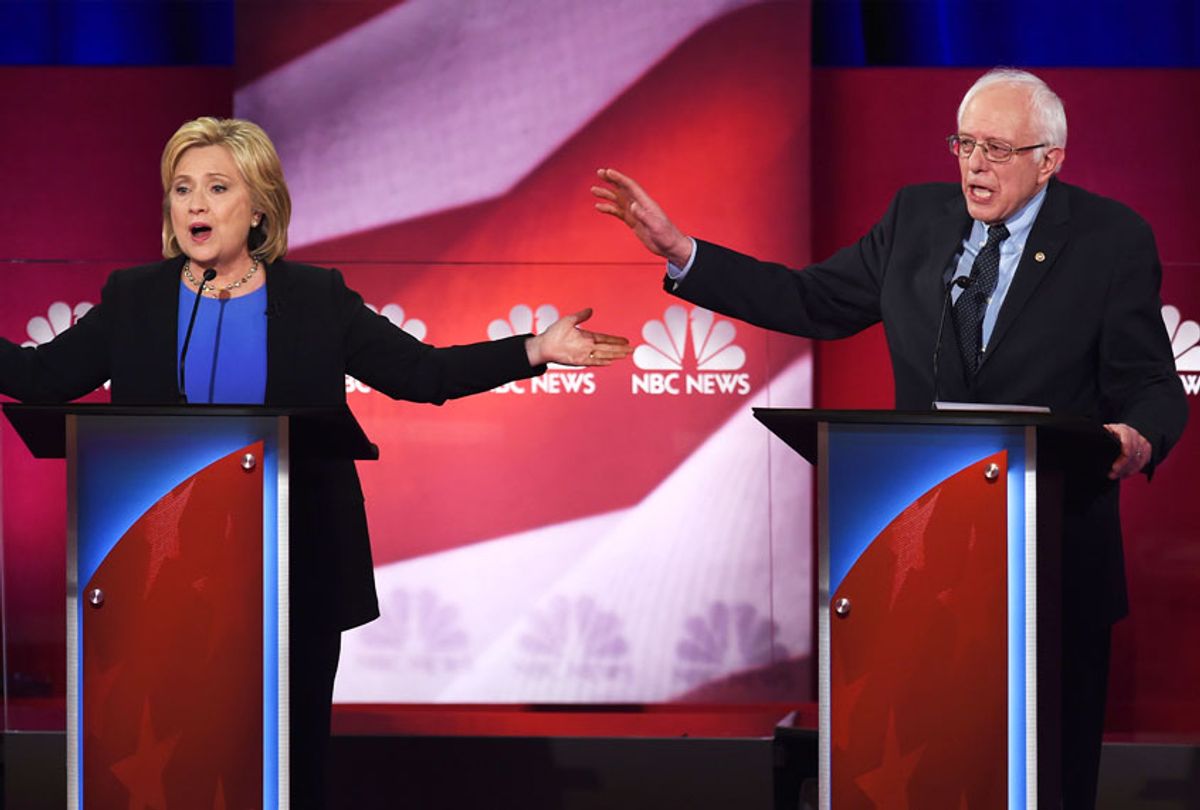

If you want to understand what's at stake in this seemingly abstract back-and-forth over the vague category of class reductionism, you just have to consider the debates over how Bernie Sanders addressed racial inequality in the country. Sanders' policy platform, broadly, was class-oriented: create a welfare state and a progressive taxation structure that would move wealth from the top to the bottom, regardless of the gender or racial composition of those at the bottom. However, income deciles in the United States are not proportional: on average, women make less, as do people of color. Hence, one might argue (and many did) that Sanders' policy platform was that of a class reductionist: it would not resolve inequalities that persist on gender and racial lines. In 2016, Hillary Clinton infamously (and disingenuously) challenged Sanders in this regard: "if we broke up the banks tomorrow… would that end racism?"

This was an indirect way of vilifying him as a class reductionist, and many observers directly invoked the label. At the time, this led to an emotionally charged discussion. Those who hurl the accusation claim their targets are denying or downplaying the significance of forms of oppression related to race, gender, and other social categories that aren't strictly economic. Meanwhile, those accused of being class reductionists retort that their accusers are adopting a posture of social justice in order to rationalize the extreme economic inequality which our political system forbids us from questioning.

There is a historical basis for the accusation of class reductionism. In some cases, social movements around class have been racially exclusionary or have failed to build equality among their members. It's also true that broad social reforms have sometimes left behind sections of the population who are subjected to special forms of discrimination.

However, this argument gives an incomplete and distorted picture of history, so when Reed characterizes it as a myth, he makes two historical points in response. First, labor and socialist movements played a fundamental role in the history of struggles against racism, because they had a broad egalitarian vision of a just society, and because equality within the working class enhanced its collective solidarity and power. (A recent study bears this out.) There are certainly examples of their failures to adequately deal with problems of race, but this doesn't change the overall importance of labor and socialist organizations in the movements against racism, from the Communist Party's campaigns against lynching in the South to the labor coalitions orchestrated by union organizers and civil rights leaders like A. Philip Randolph that were at the core of the Civil Rights Movement.

Second, the populations who are assigned racial categories like "Black" are disproportionately working class, so it's totally illogical to represent economic redistribution as being somehow against their interests. As Reed puts it: "African Americans, Latinos, and women are disproportionately poor or working class due to a long history of racial and gender discrimination in labor and housing markets." Posing racial disparity and economic inequality as somehow disconnected, separate issues will lead to a political program that totally leaves behind the majority of Black people and other working people of color — no matter how much the rhetoric may draw on current languages of social justice.

In other words, if you disconnect racial disparity and economic inequality, as Clinton and other liberals have, you end up with what Reed characterizes as "neoliberal social justice." This position amounts to arguing that "society would be fair if 1% of the population controlled 90% of the resources so long as the dominant 1% were 13% Black, 17% Latino, 50% female, 4% or whatever LGBTQ, etc." By framing justice in terms of equitable distribution, the very fact that there is a dominant 1% of the population goes unquestioned. The only political program would be diversifying the elite, rather than ending its monopoly on wealth and power. (From time to time, I ask students if this is the model of social justice they would embrace. The question is always answered with a long silence.)

So it's true that when liberals make the accusation of class reductionism, they're often falling back on historical distortions and logical fallacies. If this was all there was to Reed's argument, it would be a pretty clear-cut refutation of the way liberal elites try to rationalize economic inequality. However, Reed's argument goes much further than this, and that's where we start to run into trouble.

The trouble starts to emerge when we look at the issue of police violence. Economic inequality plays a huge role in police violence, a fact which liberal elites constantly ignore. A recent study of police killings by Harvard epidemiologist Justin Feldman shows that "rates of police killings increase in tandem with census tract poverty for the overall population." But at the same time, poverty doesn't entirely explain the fact that Black people are killed by police at a rate that is double that of whites: "Higher poverty among the Black population accounts for a meaningful, but relatively modest, portion of the Black-white gap in police killing rates."

So we have to consider two crucial points here: first of all, any antiracist political position that isn't also tied to an economic analysis clearly can't adequately explain or respond to police violence. But at the same time, a pure class-based analysis clearly isn't enough, because it doesn't explain the undeniable racial disparities.

It's absolutely true that you can't understand any form of social inequality in capitalist societies without considering class, too, and the role it plays. But Reed takes a huge leap from there, and makes two arguments that are, I think, a bridge too far.

First, Reed argues that the very category of racism is useless for understanding problems like police violence. Second, he argues that antiracism isn't a form of opposition to the status quo, or even just a basic aspect of human decency. In Reed's view, antiracism is intrinsically an aspect of "neoliberal social justice," which focuses on racial disparity as a way of rationalizing class inequality.

For example, in his article on police violence, Reed acknowledges that "available data… indicate, to the surprise of no one who isn't in willful denial, that in this country Black people make up a percentage of those killed by police that is nearly double their share of the general American population."

But after making this observation, Reed goes on to argue that "reducing discussion of killings of civilians by police to a matter of racism clouds understanding of and possibilities for effective response to the deep sources of the phenomenon."

Why would calling attention to this fact — and just generally using the word "racism" — cloud our understanding of police violence and prevent us from responding to it effectively?

Reed cites statistics which suggest that the incidences of police violence can be better explained by their concentration in lower-income neighborhoods, and it's clear that this class aspect is essential for understanding police violence. But using that as a basis for dismissing the explanatory role of "racism" altogether simply doesn't follow. First of all, as we've already seen, while economic inequality is certainly part of the explanation, it doesn't entirely explain the racial disparity.

Second, if you reframe racial disparities in class terms — by arguing that the problems generally ascribed to racism really result from the fact that Black people are disproportionately represented among the poor — you're just deferring the actual explanation. You now have to explain why Black people are disproportionately represented among the poor. This means referring to the long process by which racial and class categories were mutually constituted in American history, starting from slavery and evolving over the development of American capitalism, continuing into the present as the result of the discrimination in labor and housing markets that Reed himself points to.

There's no reason why this kind of attention to the causal factor of racism — even when it operates in a way that's relatively autonomous from the economic — should undermine an attention to class.

In fact, this is precisely the fallacy of the liberal elites who make the accusation of class reductionism: that talking about race and talking about class are ultimately incompatible. In other words, Clinton's rejoinder to Sanders — that "breaking up the banks" wouldn't end racism — is wrong. Banks have played a fundamental role in maintaining racial disparities in wealth — for example, through discriminatory lending practices — and their nationalization would go a long way towards overcoming those disparities.

In a similar way, Reed goes as far as to argue that a politics of antiracism can't successfully counteract police violence, because focusing on the racial disparity will lead to two mistakes. First, it will prevent people from addressing the root problem, which is how police violence targets the poor and enforces the upward distribution of wealth. Second, it will prevent people from building broader, cross-racial class-based coalitions that can respond to the overall patterns of police violence.

But these points don't actually follow from the premises. Pointing out a disparity doesn't commit you to reducing your politics to overcoming only this disparity, any more than supporting a workplace action for safer conditions at a meatpacking plant prevents you from supporting an action for higher wages at an Amazon warehouse. Along these lines, poor whites who are harmed by police stand to benefit considerably from movements against police violence, even if these movements start by pointing out a racial disparity.

We can sum up these problems by saying that when Reed sets out to refute the myth of class reductionism, he starts by pointing out there's actually no incompatibility between addressing racial inequality and economic inequality. But then when he proceeds to reject racism as an analytic category, and dismisses the politics of antiracism, he ends up mirroring the liberal separation between race and class.

But there's a second problem here, which has to do not with the relation between race and class, but the way we think about class itself. Since class is just assumed to be a solid foundation — something that's straightforwardly universal, and the basis of strong, inclusive coalitions, in contrast to the supposedly thorny and divisive category of race — the contradictions of class politics often go unnoticed.

In other words, the whole debate about "class reductionism" turns out to be a red herring. In fact, if the arguments made against antiracism were applied consistently, similar claims could be made about working-class struggles — that they've been irredeemably bureaucratic and sectional, easily co-opted by elites, and have revolved around shoring up a working-class "identity" within the capitalist system rather than eliminating class inequality. That is, providing better representation for the working class and supporting it with public programs doesn't change the fact that people are forced to work for wages for their survival while the owners of wealth plunder and destroy the planet to accumulate profit.

Like the critique of antiracism, this is a somewhat one-sided interpretation, and deals with big-picture problems that may seem pretty distant from our everyday political concerns. But it does show us important contradictions and challenges for class struggle that can't be ignored. It also points to long-term strategic questions that influence our short-term tactics. In the short term, arguing for a return to class-based politics doesn't provide any guarantee that there will be solidarity across different sectors of the working class, that labor organizations will really represent the interests of their rank and file, or that politicians will pursue reforms that actually benefit their working-class constituencies.

After all, history demonstrates that labor struggles don't intrinsically lead to solidarity and equality. They can limit their scope to a particular layer of workers and exclude other workers on the basis of differences like skill level. This is typical of craft unionism, for example, which organizes workers in particular trades rather than whole industries, but it's rooted in the overall way that unions are forced to operate within the logic of capitalist competition. Workers are compelled by the market to act as commodity owners who bring their labor-power to trade. From the perspective of the market unions are "firms" which set prices and conditions and generate an administrative personnel to oversee transactions and negotiate contracts. This is the underlying basis for the "business unionism" that's been so damaging to the labor movement.

So an active struggle has to be waged within class organizations to build unity and equality, as Jane McAlevey describes in her account of a hospital strike in Nevada. An important risk in labor actions at workplaces like hospitals is that they'll be limited to the "professionalized" layer of nurses — but this strike represented the whole range of workers at the hospital, from nurses to cleaners to cooks, because labor organizers made a point of "developing workplace solidarities that bridge intra-class differences." On that basis they were able to win major workplace and political victories. McAlevey points out that this kind of solidarity isn't a given, but has to be built, often against the tendencies of the existing institutions. Labor organizers have to think about "what strategic choices are needed today for forging new working-class solidarities, even in the face of existing union organizations which do not value them."

Indeed, one of the important lessons of labor history that's too often forgotten is that labor movements frequently enter into direct confrontations with the repressive wing of the state — since in the last resort even democratic capitalist societies rely on the police to preserve order. This is just one reason why labor movements have a particular interest in supporting movements against police violence, and criticizing them from a point of view supposedly based in class doesn't make any sense.

Shares