Madeline Gregg knew back in March, after the novel coronavirus was declared a global pandemic, that her 6-year-old daughter Evi probably wouldn't be physically attending first grade this upcoming school year.

When Evi was 14 months old, she was diagnosed with fanconi anemia, a rare genetic disorder resulting in impaired bone marrow function, which leads to a decrease in the production of all blood cells. For that reason, Gregg said, exposure to the flu is enough to result in Evi's hospitalization.

"So when school was initially canceled," she said, "it was a no-brainer that she wouldn't be going back to school until the majority of people are vaccinated [for the novel coronavirus]."

While vaccines can take years to research and develop, according to the New York Times, 27 vaccines for the virus are already in human trials and scientists are "racing to produce a safe and effective vaccine by next year."

But that leaves many school district leaders, educators and parents, including Gregg, in a position where they have to determine whether in-person education is the right choice for their students — and what the alternatives actually look like.

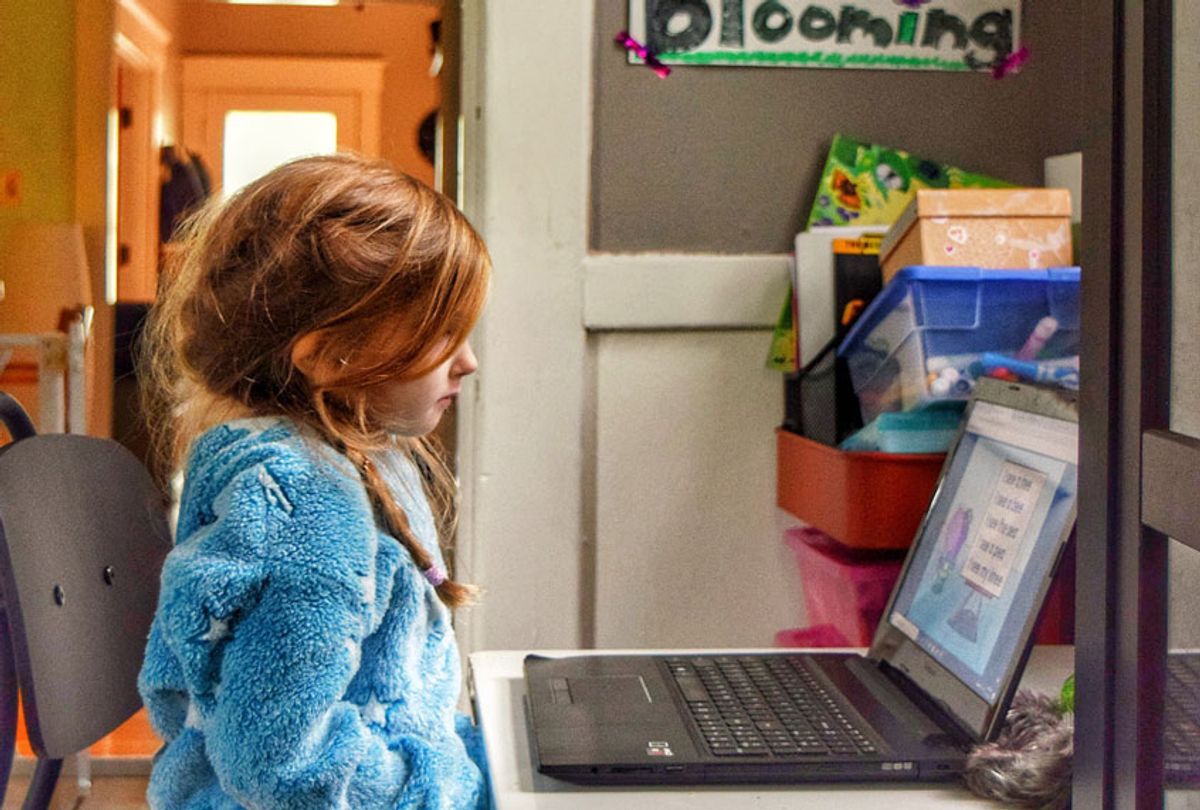

In Gregg's case, she contacted the parent of another immunocompromised child from Evi's kindergarten class in Louisville, Ky., to see if they would want to "pod together."

"And my mom, who is a retired teacher, will be homeschooling the girls three days a week for three hours a day on those days," Gregg said. "So not only will they be able to get out of the house, and have a safe environment, which is my mom's house, where we have all these rules in place so we can make sure that this 'bubble' basically doesn't pop, but they'll be able to see each other and play."

The concept of "pandemic pods" has garnered a lot of interest over the last several weeks, the idea essentially being that groups of 10 or fewer students will learn together in a home environment. Either a parent, or rotation of parents, will teach the students — or the parents of those students will pool together funding to hire an instructor.

It's a way to mitigate the health risks associated with sending students back to a physical classroom, but also allow them to enjoy a more complete educational and social experience than remote learning alone.

And while many school districts across the country have yet to announce formal plans for the start of the school year, many parents are scrambling to find their pod.

Kaylie Milliken's son is entering the first grade. She lives in California in one of the 32 counties where schools will remain closed as they are on the state's COVID-19 monitoring list due to surging coronavirus cases.

California Gov. Gavin Newson announced the shift to full-time distance learning in those counties in a July 17 press conference, the Los Angeles Times reports. The counties are home to 35.5 million Californians. "We all prefer in-classroom instructions for all the obvious reasons — social and emotional foundationally, but only, only if it can be done safely," Newsom said.

"So I've started reaching out to some of the parents of his classmates from last year to see if anyone is interested in sharing a tutor for the coming school year," Milliken said. "The problem is that we don't know who their teacher is going to be in the fall, so we're not totally sure if that's going to work."

That hasn't stopped Milliken from pricing tutors, however.

"So, I have a friend who is paying a college student $30 an hour to tutor her twin girls in third grade," she said. "So I'm kind of basing it off that. I figured it would be $25 an hour for my son and then add $5 per kid if more are interested."

According to Milliken, local "mom groups" on social media have become a popular place to try to find like-minded pod members, as well as tutors or teachers who are advertising their services on those pages. Some parents, like Kerry Wright from Louisville, have created surveys in order to pair families who are looking for pod members. "My goal is to make sort of a Match.com, but for families," she said via email.

Some teachers, like Andrew Bryzgornia, are also interested in potentially making the switch from teaching in a classroom to instructing a "pandemic pod."

Bryzgornia currently teaches math to 7th through 12th grade students at a private school in Minneapolis. When we spoke on Monday, he felt confident that Minnesota governor Tim Walz, a former public high school geography teacher, would issue a mask mandate for the upcoming school year (Walz went on to announce such a mandate on Thursday), however, he still had concerns for his and his family's health.

"My wife is pregnant with our first child. We're going to have a son, and he's due around Thanksgiving," he said. "I'm worried about getting sick and possibly dying, and then she's a single mom."

Even if students are masked, he also fears passing COVID-19 to his wife. For that reason, he's considering tutoring in a home setting during the coming school year. Bryzgornia is currently tutoring three students this summer, and the family of one of those students has already approached him regarding his availability if they opt for homeschooling rather than completing in-person classes.

"Even before she mentioned it, though, I was kind of thinking that I might be considering tutoring students in lieu of teaching this fall," he said.

Websites like Selected for Families and SchoolHouse have also launched professional services to match families with tutors and pod instructors.

The inequities of the "Pay to Pod" structure

Some education equality advocates are concerned that inherent to the "pay to pod" structure — as well as digital learning, as a whole — is the potential for vulnerable students being left behind.

Dr. David Stovall – a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago who studies the intersection of race, place and school – spoke to Salon about the challenges. Many parents do not have the resources to pay for a private pod instructor or can't afford to take off from work — or aren't in a job where they can work from home — in order to instruct their own children.

"I'm also really concerned about it because here in Chicago, what we noticed from March to June is that 60% of CPS [Chicago Public School] students never logged in for digital learning," Stovall said. "And then the other part of that is that, even before COVID, 60% of CPS students' access to internet service was actually done via phone."

He continued: "So really understanding these particular disparities in terms of access to reliable WiFi, and even the equipment to make that transition more seamless, that is a huge issue."

Stovall described how, when Chicago public schools transitioned to digital learning in the spring, he saw lines of parents that wrapped around certain schools as they were waiting to try to secure laptops for their children.

"And I think the current moment has just laid bare what we already know, right?" he said. "Like this is something that is now just exacerbated in a way that you can't unsee it, but it's always been an issue that those who are viewed as disposable have the least. When people talk about structural racism, this is the type of inequity that is ingrained into schools."

According to Stovall, the only way to address those issues is in prioritizing those who are most marginalized now in school districts.

"But many aren't willing to do that because they fear that the middle class and the affluent parents who still have kids in public schools will take them out," he said.

Stovall said that prioritizing marginalized students will look different for every district, but that all districts should move away from what he perceives as a "triage approach." Instead, he suggests considering three long-term solutions: rethinking the reliability of standardized testing, moving outside the current grading structure to measure aptitude, and restructuring the teacher performance assessment.

"The teacher performance assessment, nicknamed a TPA, entails paying $300 for somebody outside of your district to record your teaching and them being the definitive arbiter of whether or not you're prepared to teach," he said. "Now, to me, that is absolutely senseless. How is somebody actually reviewing your teaching if they don't know the context of your students, your district?"

Stovall acknowledges that given the current reality — most districts are less than a month away from resuming school in the middle of a global pandemic — things will get worse for vulnerable students before they get better. He also recognizes that most parents and teachers are simply focused on getting by in these unprecedented times.

But he holds on to hope that as more children are going to be learning outside of the classroom environment, districts will realize that the inequities facing their students can no longer be concealed behind schoolhouse walls.

"This is really that moment where we have to really come to grips with some of the structural inequities that are now exacerbated because now we don't even have the semblance normalcy," he said.

Shares