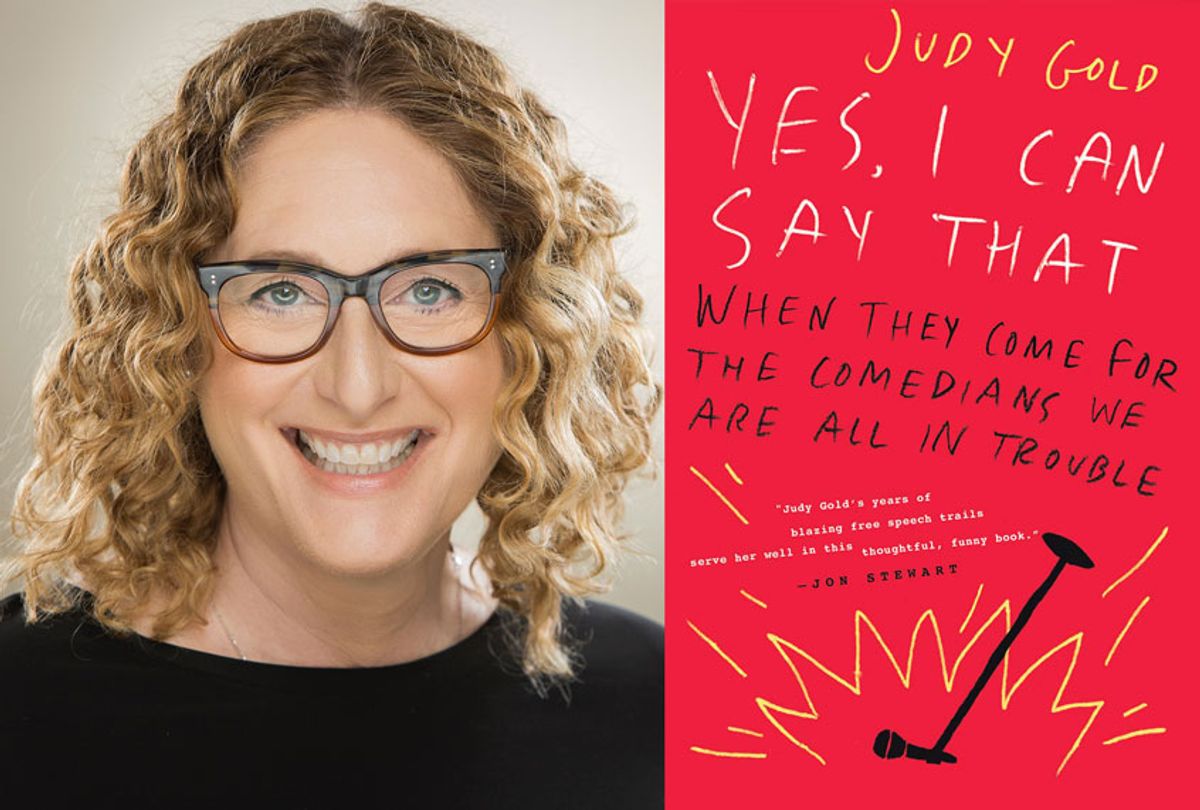

Comedians may be the one group that can reliably incite the ire of conservatives and liberals, triggering snowflakes of every conceivable stripe. As veteran comic Judy Gold points out in her self-explanatorily titled new book "Yes I Can Say That: When They Come for the Comedians, We Are All in Trouble," performers as diverse as Dave Chappelle, Michelle Wolfe and Kathy Griffin have become targets of outrage and boycotts from very different audiences but essentially for the same reason — saying things that make people uncomfortable. Which is pretty much the job description.

Salon recently talked to Gold — who is safely doing her comedy outdoors this summer in Provincetown — about parenting, her new book, and why in serious times we have to take ourselves less seriously. The following conversation has been lightly edited for lengthy and clarity.

You tell jokes that are designed to provoke, but then everyone is offended all the time. It must be very hard within that culture to have space for anything to be funny or anything to be irreverent.

If you're looking to be offended, you can find it anywhere, anywhere, anytime, but it's a choice. Everyone has a platform. Everyone thinks their voice is important. Everyone gets a trophy, and we're banning thoughts and ideas. And when there's no discourse, there's no growth. It's so incredible to me that when someone is on trial for homicide, their sentence is determined by their intent. Yet we don't give the same courtesy and consideration to a comedian. What is the comedian's intent when they tell a joke? What is the context? What are they trying to say? Guess what? It's not about you.

It may sound ridiculous to ask what, aside from everything, inspired you to write this book? But what made you decide, "I want to put this together in something other than my act"?

I was featured on "Vice News" on HBO. They did a piece on college bookers who book comedians and tell them what they can and cannot say on stage. They interviewed three bookers who are, quote unquote, "protecting the students." They asked me to be the opposing point of view, which I was happy to do. And because of that piece, which got a lot of attention, an editor at Harper Collins asked me to write this book.

It's something I'm so passionate about. Since I was a little girl, I always had no edit button. As I was writing the book and going through the history of how we got here to this place and how people fought for free speech, I'm at the clubs four or five nights a week. Some of the most edgy, subversive, incredible comics were like, "I can't do this bit. Am I going to get in trouble?" It's like, my God, we're going to be canceled for a joke.

In Seth Meyers' "Lobby Baby," he has this wonderful part in it where he says how, when he works at Catholic colleges, they say, "All we ask is that you don't make any jokes about the Catholic church." And he answers, "Oh, what kind of jokes are people making? What is it that people are saying about the Catholic church?"

Because if I don't say it, then it doesn't exist. What is this idea that we can never feel uncomfortable? We can never feel sad? That's not reality. Every "safe space" has a door to the real world.

What you are are talking about is nuanced thought. As a gay, Jewish woman, you understand that comedy has also been used as a source of strength. We're talking about groups that have suffered. It's not like this is coming from a place of punching down.

Those are also the audience members who have the best sense of humor, the ones who have had to endure hardships and have had to get out of situations with a joke or quip. Marginalized people have used humor as a weapon. It's because it's powerful. It's disarming. It heals. It educates, It connects us. And when you banish comedians, that means you're depriving us of laughter and discourse. Lenny Bruce was arrested for using foul language. But they really wanted him because he was talking about segregation and the Vietnam war and racism and homophobia and the government.

I'm a gay, I'm a Jew. I get up and talk about my experiences. In the mid-'90s, when I came out on stage as a gay parent, I was talking about my family. And after two minutes, all the straight people in the audience forgot I was gay, because it was the same issue. I had someone in Houston come up to me after a show and say, "I see now why you want to get married. I didn't see it in that way before."

You point out in the book that's different from "bad comics, substituting shock for humor, bullying people, writing sh*tty material." You still have to be good at what you do. I am reminded of the Shane Gillis controversy last year.

Shane Gillis has every right to perform standup . . . but you can't use the excuse of "pushing boundaries." No, those boundaries were pushed by geniuses before you who really were talking about substantive issues. He worked for corporations representing a television show, a network, and they decided for their business model this wasn't a good idea. That's what happens. But no one's saying, "Don't. You can't get on stage anywhere." If that's your material and if that's what you want to do, fine. But then you have to take what comes with it.

You can say whatever you want. It doesn't mean people are going to pay for it.

And it doesn't mean that it's funny and that it's educated. If you're going to joke about racism or homophobia or antisemitism, if you're going to joke about any of these issues, it better be funny and it better be coming from an educated point of view.

The other side of that is that you can be a terrible person, and be funny. In the book, you go in and you talk about Bill Cosby and the impact that his work and that his show had on people. You talk about Louis C.K. and the opportunities that he did create for women in the industry. These things can exist simultaneously. You can be a brilliant comedian, you can have a comic legacy and you can also be a person has done really crappy things.

It's sad because "The Cosby Show" was a great show and it represented people who weren't represented on television. And yet he's a sexual predator. He's a rapist. He's a horrible person. I had a driver for some gig, and right when the Cosby thing came out and he was like, "I just don't understand how he could do that." I said to the guy, "Dr. Huxtable didn't do it. Bill Cosby did it." I write about Coco Chanel in the book, a Nazi embedded with the Nazis. And yet I go to synagogue, and half the people have a Chanel scarf or Chanel suit.

It's not easy to acknowledge the talent or the artistry of someone and separate that from the person. How do we reconcile that discomfort?

Why are we avoiding it? How is that good? If we didn't hear the other side of things, we wouldn't know what we were fighting for. It makes us more educated. It makes us more openminded, less ignorant.

What is it like now to be a comic and to have this specter hanging over you all the time? No one wants to go back to the degree of racism and antisemitism and homophobia and –

I start one chapter with, "Thank God Don Rickles is dead," because if he was 20 today and out there, no one would get it. He literally was saying to everyone, we're all the same. He got people to laugh at themselves, and that's now what we're not doing. We're taking ourselves so seriously. Look at the president. He wants "SNL " investigated. There are no comics at the White House Correspondents' dinner.

So what do you do now, knowing that your livelihood is now more precarious?

I'm in a comedy club. This is my home. This is my, quote unquote, "safe space." It's the only art form that really needs the audience to inform the artist. And if you're shutting us down before we start, there's no comedy. And comedy and satire are such a big part of this country and who we are.

It's interesting because people are like, "You can't joke about COVID," and it's the perfect storm for stand-up. Everyone is in the same boat. Everyone is thinking the same thing. I have a joke: "My car is getting four months to the gallon." Doesn't make the pandemic any worse. I'm not saying this didn't happen and it's not horrible. I'm just saying, "This is what's happening. Here's the funny." That's what I do for a living. It doesn't mean that 149,000 people aren't dead and more are suffering right now. It doesn't take away from that. The speech that incites violence, that takes rights away from people, conspiracy theories, these are dangerous. We're not dangerous.

You're a parent; what do you have hope for your kids? Do you think think that the pendulum can swing in another direction?

I raised my kids to be socially aware. The one good thing about the last three and a half years is people are way more civic-minded. They know way more about what's going on in the world and how it affects them. They see how leaders and the government affect us. But I raised my kids, and other parents would complain, "I can't believe you let your kids watch 'South Park.'" I wanted my kids to know what's funny.

I was thinking recently how rarely anybody now has a conversation that's not even, "You're right, and I'm wrong and I've changed my mind," but just, "That's an interesting point. I never thought of it that way."

That's what makes a joke work, when you point out something that's been in plain sight all along, and then it becomes alive in a different way. You look at it in a way where you suddenly go, "I never noticed that. Isn't that funny?" We have to be able to laugh and not take ourselves so seriously.

Do you think it's because things are just difficult so now that we can't switch off?

I think in those times, it's even more important to find the humor. Look at when people are ill. What do they ask for? Funny movies, or, "Can you call my friend and cheer her up?" People want to laugh. And you can't say, "I don't find this funny so it's not funny and it should never be said again." If you don't like a song, what do you do? You turn it off. I don't say to that person, "Don't ever write a song again. You should never be able to perform." It's mind-boggling to me because our goal is to make you feel good. That's what we're doing. We're just trying to make you laugh.

Shares