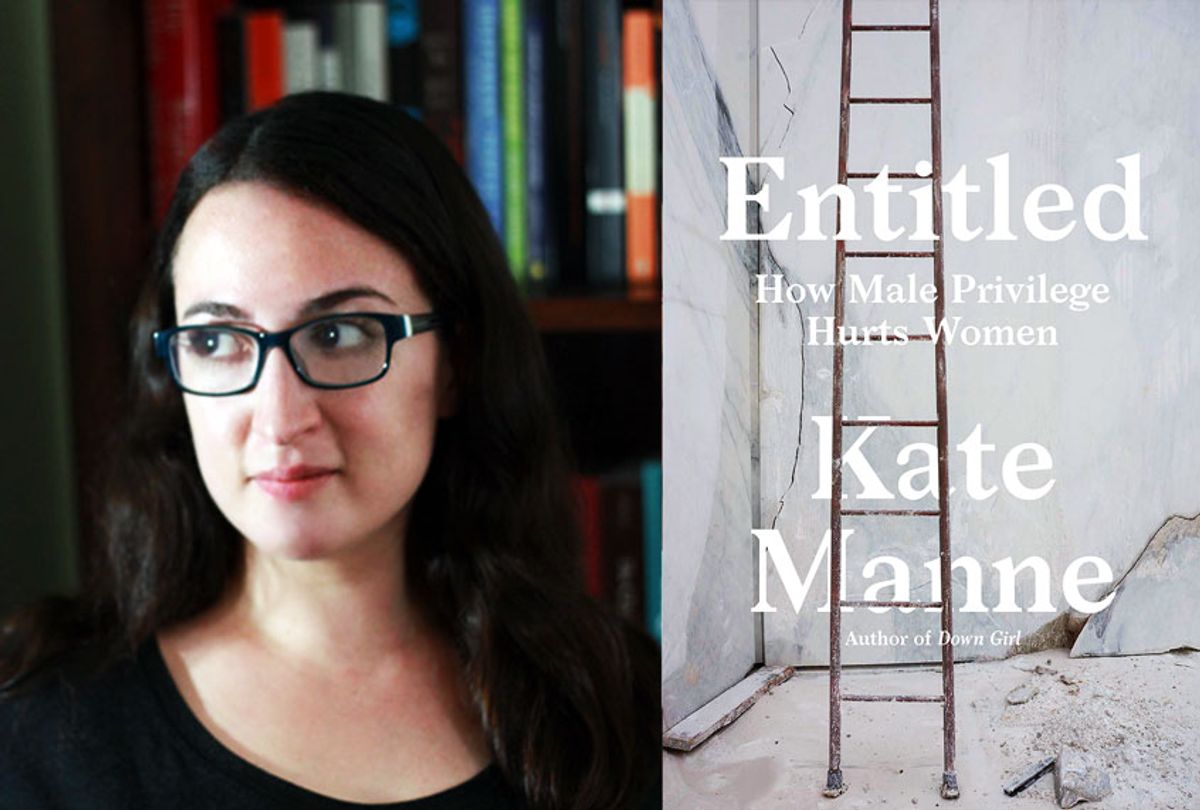

Too often, the problems of sexism and misogyny are discussed as if they were strictly women's problems, with very little discussion of why sexism is so pervasive and who benefits from this system. In her new book, "Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women" (Crown Publishing Group, Aug. 11), Cornell philosopher Kate Manne confronts the uncomfortable reality too rarely discussed, which is women are kept in a second-class status for the benefit of men, and that the only way to end sexism is to end the widespread unearned male entitlement to women's affections, women's labor, and women's deference.

Manne spoke with Salon's Amanda Marcotte (full disclosure: Marcotte blurbed Manne's book) about "Entitled," what men gain by keeping women down, and how figures like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez give us a model on how to fight back.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your first book, "Down Girl," was about how misogyny operates as a way to police women's behavior and keep them in a subservient position. This new book is about male entitlement and its effect on women. How does the thesis of this book differ from the thesis of your last book?

I see them as two halves of a whole. If misogyny is about policing and punishing women's misbehavior and enforcing their good behavior by the likes of patriarchal norms and expectations, then that immediately raises the question: What are these patriarchal norms and expectations, particularly in allegedly "post-patriarchal" context, like the U.S. today?

My answer to that is in the second book, this new book "Entitled," which argues that a lot of these norms and expectations are that women give men the goods which they're deemed entitled to, which includes sexual labor, reproductive labor, emotional labor, and material labor, among other things. Caregiving generally.

Also, we tend not to punish transgressions of men, when they're in service of extracting those goods. That leads to sympathetic reactions to men who take those goods by force. It also leads to being much less critical than we should be of misogynistic behavior that secures those goods.

It's a whole system, one that both tries to get women to supply the goods, and that goes relatively easy on men who seize those goods when they're not provided.

Obviously, where this tendency gets most serious and troubling is around the question of sexual violence. You write about the way that rape and other sexual assault continues to be treated with relative indifference compared to other crimes. People make excuses for, or overlook, assaults that Donald Trump, Brett Kavanaugh, and others have been accused of. Now that he's dead, Jeffrey Epstein is public enemy number one, but he got away with sexual abuse for decades. So how does male entitlement explain the collective indifference to sexual assault?

There's a very direct link. If we think that men are entitled to sex — and also things like sexual admiration, that incels bemoan the lack of — we're inclined to be sympathetic to men who are not just disappointed by the lack of those things in their lives, but are positively aggrieved and feel entitled to them, because there's a tacit cultural agreement that entitlement is indeed the case. We're inclined not to take them seriously in terms of accountability. The #MeToo movement has drawn constant and salutary attention to those ways in which we fail to hold perpetrators of sexual assault and harassment accountable because, I think, of a tacit sense that men are entitled to touch women with impunity, and even to sexually assault women.

There's often a sense with an incel that if he just had sexual satisfaction, via maybe a sex worker, then problem solved. Game over. And that's just not true. They really want sex as currency to buy them a sense of being revered, being admired, being desired.

One of the most perceptive things about this book is the understanding that a lot of these goods are actually very emotional. There's this tendency to think of men feeling entitled to sex as a physical thing. But you dig into the way that our society constructs male entitlement to placating, flattering attention from women. For instance, you delve into mansplaining, which has become a favorite word on the internet. What kind of male entitlement undergirds mansplaining?

I really love the question, because one of the things I was hoping to to do with this book is to show these tight connections between apparently disparate behaviors. What is the connection between an incel who feels entitled to sex versus a mansplainer? One way of characterizing a mansplainer is that he feels entitled to be the one who knows, who provides information, and who offers authoritative explanation.

The incel is someone who wants to be looked up to as someone who's sexually attractive, and the mansplainer wants to be looked up to as someone who's an authoritative source of information. And what makes both objectionable is that both feel not just that they want that admiration, but that they're entitled to have it.

One of the things you write about is the way that women are made to feel guilty, as if they're begrudging men, when we don't want to pretend to find someone sexually attractive, when we don't patiently put up with a mansplainer, when we don't indulge all these male entitlements. How is it that we have all, collectively as a society, fallen into this trap of imagining that women have all these obligations to indulge men's childish neediness?

There are two answers to this question. One is that we police other people, women into fulfilling these feudal obligations. And the other piece of the puzzle is that we police ourselves. Even for a person like me, I'm pretty much a lifelong feminist, I'm not immune to a certain amount of guilt if I don't indulge male desires or vanity. Both subtly and not so subtly, we make other people feel guilty for being a "bitch." It's incredibly common.

Speaking of the word "bitch," let's talk about how Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was called that word by Republican Ted Yoho. That story turned into a much bigger deal than I expected it would.

My hunch is that it struck a chord because it so crystallized and epitomized the way women, we're just doing our jobs and being conscientious, and a man's reaction to that minding one's own business, more or less, is to go on the attack.

It epitomizes those moments where you have no good choices. You can choose to respond, and be labeled someone who's disingenuously milking this for publicity and for your brand, as Ted Yoho and New York Times did respectively. Or you can stand down and say nothing, and let that silence be a form of complicity on behalf of other women who might need you to stand up.

I thought her response was brilliant, but seeing how even the New York Times labeled it her masterful deploying her brand rather than her speaking out about something that mattered, and so effectively painting it as cynical. I thought that was really telling and kind of gutting.

It fascinated me because I'm certain that the folks behind the writing of that New York Times article did not think they were being sexist. And yet they were doing exactly what you describe in your book, which was reacting negatively to a woman who would not indulge male entitlement.

That's so often the way misogyny works. It's via moralism. It's not the really explicit stuff, like the calling her a "fucking bitch." It's via the judgments that you just wouldn't have about a male counterpart. Instead of praising her for speaking out, and noting the power of her speech, you immediately paint it as something more superficial and something morally suspect. It was a classic "down girl" move on the part of the Times.

Do you take any optimism from the way that played out? It seemed to me that when the New York Times reacted in this misogynistic way, unintentionally, there was such an outcry on AOC's behalf. There were so many people who connected to her. Men kept telling me that they were really affected by her speech.

I'm in general really optimistic about AOC's career because I think she's someone who really understands that the way you deal with misogyny is not to sweep it under the rug, or try to minimize it, or try to assuage it. She, I think effectively, is someone who enables people to get behind her. She mobilizes people.

She's this incredibly polarizing figure, but that means she has an incredible amount of support on the left that I think is really inspiring to see. She spoke out against systemic misogyny in a powerful way. And yeah, there are many people who she both couldn't and didn't win over, but she manages to galvanize people who are able to listen to what she has to say. She does what I think is the only way to deal with misogyny really well.

You write in this book about housework and the politics of housework, which has been an ongoing issue of feminism for decades. Study after study shows that men continue to have more free time than women for one big reason: Women do more housework. And that's true even when women work as much, if not more, than men outside of the home.

Women are often blamed for this inequality. Whenever I have written about this, all I get is people saying, "Well, women are too fussy. Women care too much about it. They should just scale back their expectations." You, however, blame male entitlement for the inequality.

The most straightforward explanation for the huge disparity that we still see between how much housework and childrearing labor that men and women do, when they're in heterosexual couples, is that men feel entitled both to women's labor and also to their own leisure.

I looked at particular cases where women have tried to adjust their expectations, and have tried endless different strategies, such as the case of Jancee Dunn, who has the ominously titled book, "How Not to Hate Your Husband After Kids." She tried, for a year, a slew of different things from therapy to CIA techniques to her husband talking her down from her anger to getting the kids to do more of the housework.

In the end, the problem is that her husband is not willing to do what a normal adult member of a household where both adults work ought to do. He feels entitled to go on long bike rides. He feels entitled to take long naps and sleep in, and go to drinks parties, or whatever. And she's just left with too much to do. This isn't a problem that she and women like her can solve on their own. And women like her have really tried.

One of the most insightful things, I think, you write is about how men who don't want to do housework — which, no one wants to do housework — but they're able to leverage women's guilt, not just about having a clean house, but about asking him to do more.

There's a really interesting interaction between the emotional labor and the material labor. In order to get more of his material labor, it's arranged such that she has to ask. The asking itself becomes a form of labor, emotional labor, which often has quite a toll.

When I looked at the research on this, woman after woman was saying, "It's just not worth asking him. It's actually easier to do it myself. Doing more of the grunt work is less labor than having to ask and feel like I'm a nag, and feel guilty."

Again, that fear of feeling like a bitch. Which originates out of a sense of male entitlement that, yeah, he's entitled to relax, and he's entitled to, yeah, put his feet up at the end of the work day. And she, as a woman, and especially as a mother, should be constantly working both outside and inside the home.

Many years ago, I tried to get the phrase the "nagging differential" to take off. But people weren't into it.

I love that.

In both your first book and this book, you write a lot about incels. And I think we have a model in our head of who the incels are: Young men who've grown up in this toxic culture that teaches them male sexual entitlement, who become bitter misogynists because they feel they're not being catered to to their exact specifications.

But we also just had a murder in this country. A federal judge's son was murdered by a "men's rights activist," Roy Den Hollander, who was in his 70s. He had been a bitter misogynist for a long time. So what does this all say about how we're understanding incels? Are they really a new phenomenon, or is it just a fancy new word?

One of the things I wanted to bring out in the book of how continuous this all is. Not even just with "men's rights activists," but with perpetrators of domestic violence.

You're seeing a slightly different shape to incel murders and a typical domestic violence homicide, but they come from such a similar place and a sense of entitlement. In the incel case, entitlement to some woman, nobody in particular. In the case of a domestic violence homicide, you're seeing someone who feels entitled to the services and loyalties and emotional support of a particular woman.

With Roy Den Hollander, I mean, his sense of entitlement was so powerful. It's just an astonishing thing to read his diatribes about men's rights, i.e. entitlements, being eroded. His sense of entitlement was so potent that any hint that women's rights were being more fully instantiate, felt like a threat and an attack to him.

I think we can draw common connections between all of those kinds of mentalities, and the crimes that sometimes result from them. It's really dangerous to see incels as this new isolated internet phenomenon when, yeah, it has very broad continuity, both with MRAs and with the perpetrators of domestic violence, and dating violence, and intimate partner violence.

The last thing I want to ask you about is how can both men and women do something to fight these often invisible ways we construct male entitlement, entitlement that infringes on women's lives?

It's such a big and difficult mess to tackle. A lot of the work has to be kind of local and piecemeal, and chip away at it bit by bit.

One of the things that I hope is a liberating message people take out of the book, is that both women are often entitled to more than they're given, especially women of color. We don't have to feel guilty for asserting our rights in relation to more privileged men. As much as we can chip at that guilt, that sense of shame, and that moral disgust expressed towards women who are resisting these false narratives, I think we can make some gradual and patchy progress.

We are trying to overturn thousands of years of patriarchy here.

Exactly.

Shares