Today's weather on Jupiter, the biggest planet in our solar system, is predicted to be unpleasant: Mushballs with a side of shallow lightning.

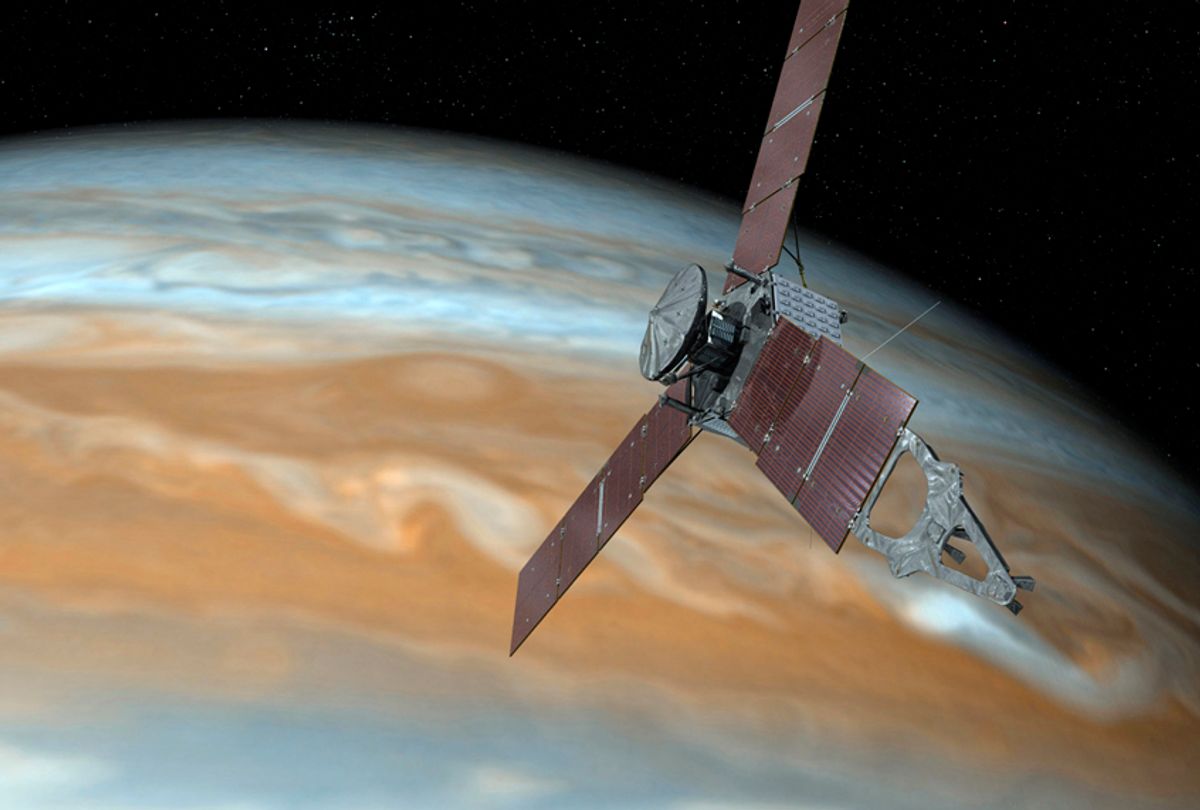

In a paper published last week in the journal Nature, and two more in Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, scientists share new insights on Jupiter's weather phenomena based on observations made with NASA's Juno spacecraft currently orbiting the planet. The analyses suggest a forecast that is distinctly alien by Earth standards, as powerful lightning strikes and otherworldly slush balls routinely pelt the gas giant.

The researchers hope that by understanding the atmospheric dynamics of Jupiter and its meteorology, they will be able to better understand the atmospheric dynamics of other planets in our solar system, as well as distant exoplanets. (Some exotic exoplanets are believed to have even stranger weather, including one where it may rain sunscreen.)

"Juno's close flybys of the cloud tops allowed us to see something surprising – smaller, shallower flashes – originating at much higher altitudes in Jupiter's atmosphere than previously assumed possible," Heidi Becker of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead author of the Nature paper, said in a statement.

In 1979, NASA's Voyager mission first discovered there was lightning on Jupiter, which drove speculations that the conditions in Jupiter's atmosphere might be similar to Earth. Specifically, clouds made of water could be creating Jovian thunderstorms, just as they do here.

Yet the pressures and temperatures that would make water-ice (meaning ice made of regular H2O) and clouds possible only occur on Jupiter some 28 to 40 miles below the visible clouds. This didn't gel with the evidence: observations of Jupiter's dark side by Juno found that there were electrical storms occurring at far higher altitudes than that.

So what was creating the lightning, if not water-ice clouds?

Based on the new observations, Becker and her team say that thunderstorms on Jupiter "fling" water-ice crystals over 16 miles above the water clouds. In this higher, colder region of Jupiter's atmosphere, these water-ice crystals collide with ammonia vapor, which melts the ice. This creates a new ammonia-water solution, which generates these high-altitude electrical storms that Juno observed.

"At these altitudes, the ammonia acts like an antifreeze, lowering the melting point of water-ice and allowing the formation of a cloud with ammonia-water liquid," Becker said. "In this new state, falling droplets of ammonia-water liquid can collide with the upgoing water-ice crystals and electrify the clouds."

In other words, a collision between water-ice crystals going up and falling ammonia-water slush going down creates the shallow lightning scientists observe.

According to the NASA release, the shallow lightning solves another puzzle regarding the amount of ammonia in the gas giant's atmosphere. In Juno's observations, ammonia was not observed in most of Jupiter's atmosphere. It turns out that it was there — but just not at the edge of the atmosphere where Juno's instruments could see well.

"Previously, scientists realized there were small pockets of missing ammonia, but no one realized how deep these pockets went or that they covered most of Jupiter," Scott Bolton, Juno's principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in the NASA statement. "We were struggling to explain the ammonia depletion with ammonia-water rain alone, but the rain couldn't go deep enough to match the observations."

Bolton said discovering the shallow lightning gave the scientists the evidence they needed to know that the ammonia "mixes with water high in the atmosphere, and thus the lightning was a key piece of the puzzle."

NASA posted a video visualization on YouTube (complete with a dramatic soundtrack by Greek composer Vangelis).

The mush balls are a whole different ball game on Jupiter, but they're also made up of ammonia. According to the paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, a combination of two-third water and one-third ammonia gas is perfect for Jovian hailstones, which are also known as "mushballs." These mushballs are basically water-ammonia slush, and they are created in a similar way that hail is on Earth. As they move up and down the atmosphere, they grow bigger.

"Eventually, the mushballs get so big, even the updrafts can't hold them, and they fall deeper into the atmosphere, encountering even warmer temperatures, where they eventually evaporate completely," Tristan Guillot, a Juno co-investigator from the Université Côte d'Azur in Nice, France, and lead author of the second paper, said in the release. "Their action drags ammonia and water down to deep levels in the planet's atmosphere."

In other words, the ammonia is deeper in the atmosphere, beyond what could be seen by Juno's Microwave Radiometer. That explains the "missing" ammonia.

"This was a big surprise, as ammonia-water clouds do not exist on Earth," Guillot said.

Shares