Imagine the fall of a major gang in an American city. A notorious gang, convicted of robbing drug dealers and then selling their drugs, along with racketeering, extortion, dressing as a mailman to robbing citizens, stealing tips from strippers minutes after they left the pole and various other crimes that caused people to die. You'd be happy to see them jailed, right?

Well this happened in Baltimore, my hometown, and that gang was the Gun Trace Task Force, made up of numerous celebrated police officers, including Evodio Hendrix, Maurice Ward, Daniel Hersl, Marcus Taylor, Wayne Jenkins, Thomas Allers, Jemell Rayam and Momodu Gondo. These guys used their badges to rob and pillage for years, while receiving praise and rewards from Baltimore City's highest officials.

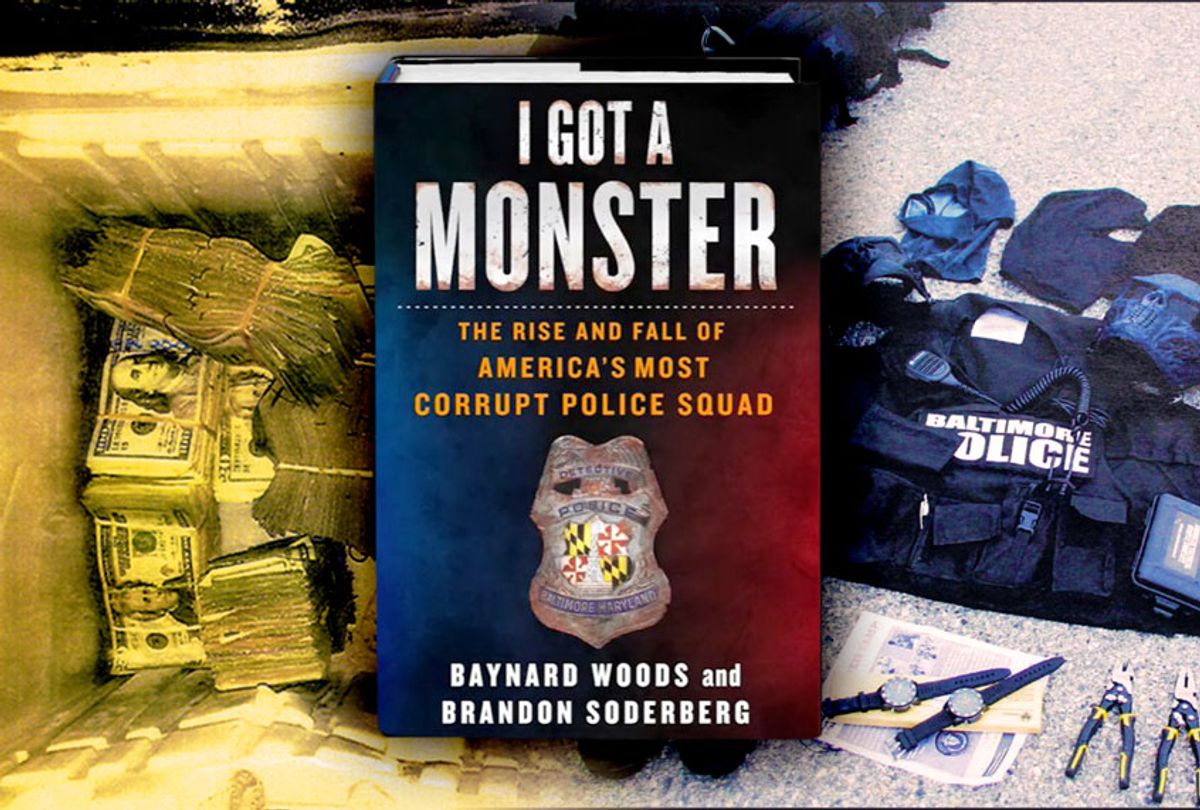

Veteran editors and journalists Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg deliver a deep dive into the history of these officers, the system that protected them and the victims who continue to suffer as a result of their actions in their new book "I Got a Monster: The Rise and Fall of America's Most Corrupt Police Squad." Woods, Soderberg and I recently discussed this extraordinary and disturbing saga on a recent episode of "Salon Talks."

You can watch my episode with Woods and Soderberg here, or read a transcript of our conversation below to hear more about how we could defunding police in a way that actually works, and what Baltimore needs to do to build trust in its historically failed system.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

First, I want to say congratulations on your book. I know it's a difficult task to cover this type of content and it's even harder when you put it out into this world. I feel like police officers who know you guys wrote this book are going to hate you forever. What does that feel like?

Baynard Woods: It's good that our pictures aren't in the back of the book. It just has our bio and no photos. So, that is sort of again, when we're outside now, that's the one good thing about the masks, is they don't know who we are at the moment.

Brandon Soderberg: We had some kind of fun. We had a couple of scary things when we were doing the reporting for the book too, a couple of times where we sort of felt like we were being kind of followed or messed with. So we've been sort of thinking about that. So having masks is good right now.

So you guys met at the Baltimore City Paper?

Woods: Like most relationships around writing and stuff, we knew each other through the editorial process first. Before we ever met, Brandon was doing stories and I would end up either editing or later on in the process, proofing the stories. We would email back and forth about that a little bit, and then we brought him in to work full-time there.

Soderberg: Yeah, I started as a fact-checker, music editor, film editor. I had three or four jobs and I shared a cubicle with Baynard, so we got to know each other pretty well.

I know both of you guys as editors and you have different styles. Were there any beefs as you guys worked on this project together?

Woods: We were each other's editors for a long time and we'd edited each other so much that in some ways this is the most edited book in history because every new pass was us editing each other. I think we were able to really create a style that is unique — it's not my style and it's not Brandon's style — but it's a style that's unique to the book.

The subtitle of your book is "The Rise and Fall of America's Most Corrupt Police Squad" and I feel like people in Chicago are thinking, "No, we have the most corrupt squad" and in L.A., they're like, "We made history as the most corrupt squad." A lot of our viewers aren't in Baltimore, so could you tell people about the Gun Trace Task Force in Baltimore? Who were they?

Soderberg: There were seven Baltimore police officers working together in a sort of gun-seizing police squad, plainclothes police. Generally no uniforms, maybe a vest, cargo pants and driving around in unmarked cars. Those guys, seven of those officers, were federally indicted on March 1, 2017, for something similar to what they usually charge the Mafia or gangs, like RICO and conspiracy charges. What the cops are charged with was a series of things, including stealing from residents, dealing drugs, stealing a lot of overtime, violating people's rights. The book deals with how they were doing all that, while also being police. And then there's another side which I'll kick it to Baynard, which is sort of these series of co-conspirators that we'e also helping them deal drugs.

Woods: Yeah, I go back to a second big question of, why are these guys the most corrupt? I mean, one of the things is that they were all doing separate corrupt things before they even came together. Three different guys had their own private drug dealers that they would funnel drugs to. One of them, [Jemell] Rayam, was a Philadelphia cop, so it went into Philadelphia. Another one was a bail bondsman who worked in the court system who was selling drugs for [Wayne] Jenkins. And then [Momodu] Gando had this group of guys that were selling heroin out of a shopping center in Northeast Baltimore.

The feds got really interested in them because they were selling heroin to white people in Harford County, which is a more rural county outside of Baltimore, and so they started trying to trace that dope back into the city. With the opioid crisis and once it was hitting white communities, the real worry about opioids in the community. They were going to go hard after these guys, and when they got a wire up on one of their phones, they found out that he was talking to Gondo, one of the cops. That's one of the important things to it, they never would have found out about these guys and what they were doing, if they hadn't been doing their ordinary, like, going after drugs or stuff. It wasn't that they were looking for corruption. They were looking to arrest another black man who was selling heroin to a white person. But all of that corruption just spirals out and out and out, and once they get together, all of those different kinds of corruption fuel each other.

The crazy part about it is as "wow" as this story was, as shocking as it was, I still feel like nationally it was underreported. Maybe a couple of pieces in the Times, a couple of pieces in some other newspapers, but it didn't get a fraction of the credit it deserves.

Woods: Yeah. I mean, the BBC did a really good job as the only like really national or international coverage, just because of one reporter's dedication. Jessica Lussenhop was really dedicated to the story and would come up to the hearings and stuff. But yeah, the Times would do these really cursory reports. I covered all of the trials of officers who were charged in Freddie Gray's death, and that was hugely important, but the trials amounted to the seatbelt policy of BPD being discussed for hours and hours and hours on end. Every reporter in America was there. And then you heard these crazy stories about robbing strippers and dressing as a mailman to sneak into people's houses to rob them and snowballs of cocaine exploding in the ground, and no one is there to cover it.

Soderberg: Also, I think that the way that we're kind of in this moment right now, again, where people, especially white people are like, "Oh, maybe the police are bad," we were kind of out of that in 2017 and in 2018, when this scandal was exposed. Everyone was really on Trump suddenly issues of policing and police brutality and Black Lives Matter got pushed to the side. The story just happened in a moment where the press was focused on something else.

The same way the media sucks at covering Trump, they kind of suck at covering police cause they're always trying to make it evenhanded and fair and make sense. And this story is just so bonkers and so big that I think that a lot of the press struggles with: How do you cover it as a story that fits into police corruption? It's really a gang story where the gang is just the police. I think that's really hard for a lot of papers to conceptualize, and I think they're just like, "Oh, that shit happens in Baltimore." So, whatever, no need to cover that.

Can you guys talk about some of the crazy stories that are in this book, like the police dressing up like the mailman, robbing strippers? There are all these different stories that will blow people's minds.

Woods: One of the important things to keep in mind is that the book really is relevant to what people are thinking about right now because it's a post-uprising book. And it looks at the way that the police were acting as a kind of counterinsurgency after a popular revolt against police. They were not only enriching themselves, they were also empowering the police department and trying to take power back. During the uprising, one of the crazy stories that I think people don't know enough about is that everyone saw the CVS pharmacy burning on TV in Baltimore. And then, later on, the police commissioner said, "Oh, the murder spike is a result of all of those stolen drugs disrupting the supply chain and causing all of this." And one of the things that is revealed in this is that Wayne Jenkins, the main sergeant, was robbing people who were robbing drugs, and taking those drugs to his bail bondsman friend in the county. And then he was selling those drugs. Some portion of the drugs taken were taken by cops. And he was given a Bronze Star for what he did that day.

Just to unpack that, an award-winning, poster child, a person who other police officers looked up to and who leadership gave medals to, especially for the way he tried to look out for officers during the uprising after Freddie Gray was killed, was actually one of the biggest drug dealers at that particular time.

Woods: Yeah, because that wasn't just a one-time thing of going to the bail bondsman's house, he'd go there every night, sometimes. There was a shed out behind the house, and if it wasn't a real big drop-off, he'd just open up the shed. And even after they got indicted, they didn't arrest the bail bondsman for another several months. And the amount of stuff they found in there, more than 235 grams of crack — because he wasn't selling crack, but it kept coming — tons of heroin that he wouldn't sell because he had a daughter who had struggled with it. He was mainly just a coke dealer, and a bunch of weed. And this was after he had months to get rid of stuff. Just the amount of drugs coming through was crazy.

Soderberg: The thing to think about, too, is that they were robbing people or rolling up on people every night for months and months together. The seven officers that were initially indicted were together as a unit for about six months. They were all doing crimes before that, but they had this moment where they all came together and had this crime spree. And that included constantly running up on people and throwing them against the wall or tackling them, searching them for drugs, taking those drugs. There's a story about a couple that they followed out of Home Depot and they illegally detain them. They didn't really arrest them. There's nothing to arrest them for. Took them back to a school that's now a police station, interrogated them, kind of like a black site. Then they took them to their house and robbed them about $70,000.

There was a guy, who Baynard kind of alluded to earlier, that they chased. They suspected him of being a cocaine dealer. The guy was driving away and he started throwing the cocaine out the window. So there's just a chase through Herring Run Park in East Baltimore of cocaine being thrown out the window. They capture this guy and at the same time that's happening, the sergeant that we've mentioned, Jenkins, is calling the bail-bondsman guy to break into this cocaine dealer's storage space to get more of the cocaine out. There were terrible things that happened, but then there's so much weird slapstick to it too.

Another one that I think is really important and terrible is there was a person that they arrested and stole $10,000 from, and he was later killed because he couldn't pay a drug debt back. Their theft of $10,000 from someone was directly connected to the reason he was killed. And that's really important to think about with these guys. It's not only the cops committing crime, but they're creating crime. The repercussions of their actions are getting people killed or hurt.

Woods: They stole $200,000 from one guy that they were illegally tracking. They followed him, they got his keys, they broke into his house. Then they got a warrant after they'd already been in there, they broke open a safe, and filmed themselves breaking open the safe after they'd already stolen the money, to make it look legitimate. So they're targeting really big-time people like that, but they're also robbing homeless people on the street.

They went to a pigeon supply store where you buy bird seed and stuff for a legitimate thing. They noticed that the people had money. So Rayam, one of the cops, gave two of his friends, who weren't cops, police vests. Those people raided the house of the people who own the pigeon store and stole their money and left. They were dressed as police but weren't real police.

Home invasions — they kicked in the door of one guy they thought wasn't going to be there. His girlfriend who was going to law school was in the bed, and the cop pointed the gun at her head said, "Where's the money?" The extent of their crimes, from the massive to the really petty, it was pretty constant.

Initially when this all came out, there were a lot of people in leadership in Baltimore saying "Oh, we got these guys and they're just a few bad apples." Deconstruct this bad-apples argument and why it's just straight bulls**t.

Soderberg: They always begin with this. The original saying is that a few bad apples spoil the whole bunch. Officials have sort of bastardized the phrasing itself and use it to mean the opposite of what initially meant. But in this case you had the initial seven officers, but a few months later, another former sergeant working with these guys was indicted. Not long after that, very famously, a cop that used to work with them, Sean Suiter, was found dead. Some people say it was a suicide. Some people think it's a homicide. I mean, I don't know. We don't solve that in the book, but what I would say is that what we definitely see that if it was a suicide or a homicide, the police killed him because either his involvement in police fraud made him fearful for his life or racked him with guilt, and he killed himself, or he was killed because police wanted to silence him. I don't want to speculate. I feel really uncomfortable with speculating on someone's suicide, but I do think that you can say that whatever happened to him was a result of his involvement with the Baltimore Police Department.

Woods: It's also important to note on that end, to the bad-apple thing, that the sergeant who was the lead detective on the Sean Suiter case, and at one point a homicide detective, was criminally charged last week for taking a contractor whose work he was unsatisfied with to the bank with his three partners and forcing the guy to write a certified check. This idea of, "Oh, it's just a few bad apples," rather than, this is what power does to people, that kind of thing points to having this kind of unlimited power. It also brings a lot more questions into what was happening with the Suiter investigation and what we know about that.

Did the contractor get his money back?

Woods: He probably will, but I bet he hasn't yet. In two years, he'll get it back. Probably.

Soderberg: Yeah, I was going to say, then you have the trial for two of the officers who didn't plead guilty. Somewhere around a dozen or so other names were involved, most of whom have since then not gotten in any trouble. What I kept seeing is these concentric circles of corruption, and you would find out that this cop is tied to this cop. So the bad-apples thing, I mean, I don't know what percentage of the department has to be doing illegal shit for it to no longer be bad apples, but we're pushing, like, 50 or 60 cops. And of course, as far as we still know the investigation is still ongoing. It's not like it's all wrapped up. Even the federal government hasn't said, "Oh yeah, we found all the bad apples, keep it moving." They're still looking into it.

How has leadership in Baltimore been responding to this problem?

Woods: Horribly. This is one of the other things that people can learn in other places is that every half measure of reform for policing is met by resistance from police and almost an intentional creation of chaos or crime in order to show how important police are. That's one of the pieces of the GGTF story. The mayor, when they got indicted, is now doing a prison term herself. The police commissioner, who was made commissioner a week before they started their trial, just got out of prison with a nice man-bun himself. The leadership has been just a disaster.

He's talking about defunding police now. He said that he was going to do that as a commissioner, if he didn't get arrested.

Woods: He was defunding police by stealing the tax money that would normally go to pay police budgets and keeping them for himself.

In addition to the book, you guys are working on some sort of film project to go along with it. Can you talk about that?

Woods: Yeah, it was going to premiere at the Maryland Film Festival this year. We've been working on it with Alpine Labs since almost immediately after we started thinking about writing the book. They were came here from L.A. and spent a summer and then another, the next summer. We filmed a ton of interviews, enough to do a series. Now, since everything got stopped, we're figuring out what to do with it.

Wendel Patrick, a Baltimore composer, scored it. It's a really beautiful Baltimore project because it was able to focus on the voices of the victims a lot more — the people that the GGTF tyrannized for all this time. It's the people like the Freddie Grays and the George Floyds who survived. To hear their voices directly and hear them talking about these experiences they had with police is, I think, a really powerful thing.

Shares