As the presidential election approaches, everyone wants to know who will win.

But nobody wants to wait until the election is actually over and the votes are all counted up and double-checked.

In an effort to predict the winner weeks, or even months, in advance, pollsters take to the phones and the internet, and academics take to spreadsheets of statistics.

Some of these analysts boast impressive track records, but take caution from a political scientist who delves into the data frequently: These methods may not necessarily be more accurate than any other method of predicting the future. For some, it's not so different from consulting Ouija boards and reading tea leaves.

The next Nostradamus?

Several political analysts have made names for themselves as predictors of election outcomes.

In the wake of the 2016 election, one political predictor, James Campbell at the University at Buffalo, a longtime professor of political science, said forecasting models had been more accurate than the widely swinging public opinion polls. He listed several examples, along with how well they had predicted the election's outcome.

One of the people on his list was Stony Brook University political scientist Helmut Norpoth, who back in March 2016, eight months before Election Day, had declared there was a 91% chance that Donald Trump would win. He claims to have a system capable of predicting the winner of every election outcome but two, all the way back to 1912.

Instead of relying on polls, Norpoth's analysis, called "The Primary Model," looks at the results of primary elections. For 2020, he observes that Trump won the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries by wide margins, and therefore predicts the president will do better than Biden, who split those primaries with Bernie Sanders.

American University historian Allan Lichtman was another star political forecaster, who called the 2016 election for Trump in September 2016. He has identified 13 factors he calls "keys to the White House," which include whether one candidate is an incumbent, whether the nomination was contested, whether there is a third party challenge, and Lichtman's own assessment of the national economic conditions, the presence of a major scandal or major policy changes, as well as his views of the candidates' charisma.

Lichtman claims he has been right about every presidential election since 1984, and says he predicts Trump will lose to Biden in 2020.

Is it a nice day in Wyoming?

Pomona College economist Gary Smith warns that these sorts of methods are not necessarily as robust as they may seem. Statistically speaking, he notes, "any 10 observations can always be predicted perfectly … with nine … explanatory variables."

To demonstrate this, he used the high temperature on Election Day in five small cities across the country to create a prediction for the 2016 election, which matched up very well — at least from 1980 to 2016.

That and other examples he provides are reminders that with enough data, "spurious correlations" are everywhere — such as the famous example that from 2000 to 2009, the divorce rate in Maine was very closely matched to the per-capita consumption of margarine in the U.S.

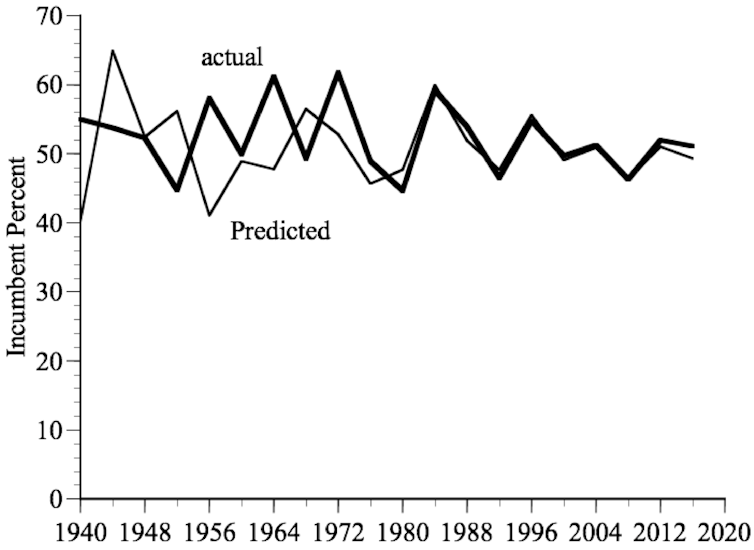

NFL fans may recall the "Washington Rule," which claimed that if the Washington, D.C., football team won its last home game before Election Day, the party in the White House would keep it. Sportswriters claimed it would predict every election from 1940 to 2000 — but since then, it has only gotten the 2008 result correct, and has been largely discarded.

From 1980 to 2016, the average temperature in five particular U.S. cities on Election Day matched up very well with the percentage of the popular vote that the party currently in the White House received. Gary Smith, Mind Matters

Hindsight in 2020 is 20/20

Of course, scholars' political forecasting models do incorporate information that could be linked to the elections. For instance, I believe that party unity, economic performance, scandals and incumbency are some of the most important factors in how elections turn out.

But economist and weather-based prognosticator Smith is correct when he points out that some of these systems "predict past elections astonishingly well and then do poorly with new elections and must be tweaked, after the fact, to 'correct' for these mispredictions." In fact, both Lichtman and Norpoth have made changes to their analysis methods over time.

They may need more tweaks in 2020, in part because they leave out factors that haven't been important in the past, but might be vital now. For instance, election officials across the country are expecting a flood of mail-in ballots and early voting. The New York Times finds that a record 76% of Americans can vote by mail, and Gallup polling says 64% of Americans support voting by mail. Those figures are far beyond even the 40% of votes cast in those ways in the 2016 election. In the past, when new methods of voting have emerged, outcomes have been harder to predict.

The forecasts may be interesting, and — like the polls — often grab headlines, but you probably don't want to bet too much money based on what they say.

John A. Tures, Professor of Political Science, LaGrange College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Shares