So here we are, exactly where we knew we would be — except it's worlds away from anything anyone could have expected. With the Democratic convention just behind us, the no-doubt-ghastly Republican convention just ahead and the nation afflicted with the worst pandemic in 100 years and a bottomless economic depression, we are poised on the brink of the most godawful election campaign of the media-politics age. It will be 10 weeks of anguish, torment and viciousness that we all believe will decide everything but may just as well, in the harsh light of history, be deemed to have decided nothing.

Donald Trump — a bereaved and wounded toddler who has been pumped full of fluid or gas and inflated to the approximate scale of a man, or at least a man-sized blimp — is howling with outrage at the unfairness of the possibility that the voters will throw him out for being incompetent and terrible, or indeed that they get to vote at all (if it isn't for him). There is simply no way to measure or calculate the surreal character of a moment in which the president of the United States announces, not once by way of misstatement but many times, that only two election outcomes are possible: He wins, or the whole thing was "rigged."

Perhaps Trump understands this as a form of magical incantation; after all, he said the same thing four years ago, and it seemed to work. But the strangest part of our tragicomical national dilemma, the part that makes it seem as if reality has been replaced with a Plato's-cave shadow play acted out by those giant humanoid windsock puppets seen outside car dealerships in suburbia, is that most of us barely notice when Trump says these things.

I don't know that "normalized" is the right word, because no one perceives the current situation as normal; it's more that we have become hardened to it, like abuse victims or soldiers in combat or homicide detectives. Oh, once in a while the inane or terrible things Trump says make headlines, as when he suggested that people shoot up with bleach, or threatened to order the military occupation of American cities. But as those examples suggest, it takes a lot. This is a person, after all, who is roundly despised by members of his own family — not just his niece, Mary Trump, but as we have just learned, also his sister, retired federal judge Maryanne Trump Barry — yet somehow retains the unquestioning devotion of millions of Americans. (I think there's a compelling argument that Trump's adult children hate him as well, but have been so badly brutalized and brainwashed they don't know it yet.)

Last week's Democratic National Convention was generally deemed a success — at least by the people who have a lot invested in believing it was a success. I'm not just being cynical; I'm also pointing out that there's a Schrödinger's-cat paradox built into American political discourse, which the Trump era has made worse. We should have learned this in 2016, but the lesson has been only partly absorbed: No one is a disinterested observer who can tell you what things mean or what will happen, and in any case, as Joan Didion noted 30 years ago, journalists have abandoned the task of "observing the observable" in an effort to turn themselves into priests or oracles.

It's not merely that political pundits are obsessed with horse-race drama and pop-psychology issues of messaging, although that's bad enough. It's also that they are entirely unaware of the way their own perspectives shape what they're seeing or how they interpret it. Most political punditry is just bad theater criticism in disguise, in which commentators either make the mistake of assuming that what they see as normal and reassuring — calls for bipartisanship, compromise and moderation, for instance — is also what will "work," or the mistake of assuming that cruelty, idiocy and fear are the baseline of American humanity and that the worst kinds of mendacity will inevitably prevail.

I certainly share the consensus view that Joe Biden gave the best speech of his life last Thursday night — I did not believe him capable of such a performance, to be honest — and that everything about the national temperature and wind direction indicates a sweeping victory by Democrats up and down the ballot in November. But it is always useful to recall the legendary maxim of screenwriter William Goldman: "Nobody knows anything." In this context, that translates to the certainty that some aspect of conventional wisdom is completely wrong, but of course we can't see what that is.

Biden and the Democrats did about the best they could with what they had, and their all-virtual convention was a far cry from the dewy-eyed overconfidence of the one I attended in Philadelphia four summers ago, where (as I wrote at the time) all the nice, normal people assembled to launch the First Woman President had no idea what was waiting for them, out there in the angry, crazy darkness of America.

Since the beginning of the 2020 campaign I have been openly skeptical that Joe Biden was remotely equipped for this historical moment, but that debate is purely academic right now. So the desperate need of the anti-Trump majority has seized on the admirable qualities Biden seems to possess, which are personal rather than political or ideological: He appears to be a kind and honorable person who has suffered terrible losses and thereby learned empathy for the suffering of others; he's a loving father, grandfather and uncle who has built around him a Kennedy-style empire of deeply loyal family members, advisers and friends.

As Biden himself repeatedly emphasized in his acceptance speech, this election is now being fought on the terrain of "decency" and "character," where on one hand the contrast between him and Donald Trump could not possibly be clearer, and on the other hand the terms of combat are fatally murky. Bill Moyers told me years ago, when I asked him about the issue of character in politics — I believe we were discussing George W. Bush at the time — that he thought it was completely irrelevant. He offered the example of Lyndon Johnson, with whom he had worked closely, a famously mean-spirited and vindictive person who was also an immensely skillful and effective political leader.

I think the point is worth making: Bill was observing that American elections are far too concerned with mystical or illusory qualities, as with the famous question of who you'd rather have a beer with, rather than issues of political substance. Yet I thought then, and think now, that it's a bit more complicated than that: Didn't Lyndon Johnson's character issues — his arrogant assumption that he was smarter and tougher than anyone else — lead him to believe he could fight on to victory in the gruesome disaster of Vietnam, long after public opinion had turned against him? Didn't George W. Bush's character flaws — which were entirely different from LBJ's, to be sure, but produced the same level of overconfidence — lure him into the even more destructive foreign-policy catastrophes of Iraq and Afghanistan?

Bill was also making the point, perhaps, that questions of decency and morality are always subjective and — like the question of whether the Democratic convention was a heartwarming tribute to the American spirit or a soulless PBS telethon — tell us more about the observers and commentators than about their putative subjects. It seems inarguable that the coronavirus pandemic and the economic collapse have exposed Trump's worst character flaws. But again, what I'm really saying is that it seems inarguable to people like you and me and readers of Salon, who never believed he was either an honorable person or a useful political leader in the first place.

In our recent Salon Talks conversation, Russian-born journalist and author Masha Gessen made a crucial point about the Trump era and the rise of autocracy around the world: The so-called institutions of democracy, which the political and media elite have constantly assured us would eventually defeat Trump, are powerless against those who do not believe in either institutions or democracy. Similarly, a presidential campaign fought on the supposedly clarifying and anti-ideological terrain of "character" and "decency" will have no effect on people who have concluded that character is bullshit and who do not want decency.

Which side of the American divide is being more honest and truthful about the fundamental nature of politics and human society? My only conclusion is that the answer is unclear, and will remain so. No one can possibly believe that Trump's supporters voted for him in 2016 because they thought he was a kind and honorable person or a loving father figure. They voted for him because he's an asshole, a bigot and a bully, and they convinced themselves either that those qualities would make him an effective leader or that he would break things and punish the people they blamed for their sense of failure or their constrained and foreshortened lives.

I suppose some tiny tranche of borderline Republican voters may be lured away by the Lincoln Project argument that the guy they reluctantly supported four years ago has proven to be an ignorant and incompetent loser. But Trump's political problem in the fall of 2020 is not that he has been revealed as a terrible person, a pathological liar and a malignant narcissist. I mean, please. It's more that he has not broken as many things quite as thoroughly as his worshipers might have liked.

In that sense, the defenders of the institutions (or as Trump would put it, the "deep state") have a point. Trump's greatest disappointment as president has been the discovery, contrary to his imaginative reading of Article II of the Constitution, that he does not possess unlimited power, not even over the federal bureaucracy.

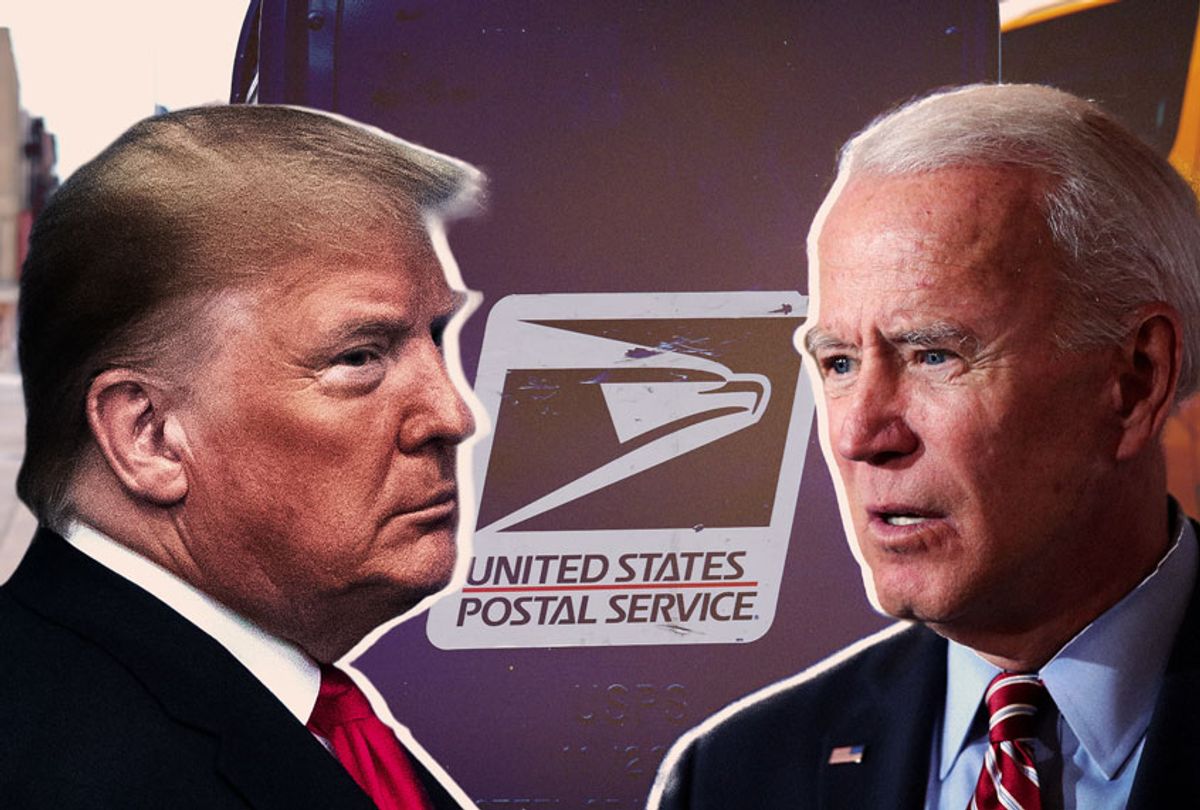

He has certainly done his utmost to wreck the upper layers of government, and the damage may take decades or generations to undo. But still: Just this week, the Postal Service police — how's that for situational irony? — arrested Steve Bannon on board his borrowed yacht, for a financial grift so blatant that even Trump had to back away and pretend he barely knows the guy. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy has been compelled to promise that mail-in ballots will be delivered on time, and that particular election-rigging scheme has been at least partly defused. The FDA, to Trump's immense displeasure, has made clear that it won't rush out an untested coronavirus vaccine, Putin-style, just so he can claim he has solved the crisis he bungled so dreadfully.

Once Trump is finally out of office — and I'm inclined to believe that will actually happen in January, with a less-than-apocalyptic level of histrionics — America's real problems will remain unsolved, because they created him more than the other way around. As for the question of whether Trump and his decaying empire of penny-ante corruption will face any real consequences once he's no longer protected by his pseudo-imperial office — well, I understand why people care about that, as a matter of symbolic justice, but I'm not much interested.

Joe Biden and his attorney general will surely want to turn the page and move on, for better or worse. Maybe the postal police have been building a case against Trump and his family this whole time. They clearly have grounds and standing — and the American people are united behind them, if about literally nothing else.

Shares