Among the various inaccurate things my father told me about American politics was the truism that presidential campaigns began on Labor Day. If only, right? In our near-psychotic media dystopia, political campaigning never ends and, indeed, to a large degree has taken the place of actual governing, especially under President You Know Who.

Still, something feels different as we turn the corner into fall. To borrow a strange construction the New York Times used on Sunday, “the campaign enters an intense phase,” as if it were a natural phenomenon like a hurricane, moving and changing without human intervention. To put it another way, quoting the final hit song from the late Leonard Cohen, you want it darker?

I suppose the truism about no electioneering before Labor Day was a little bit true, a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. In my dad’s version it was an inflexible article of the gentlemanly code of political combat, vaguely akin to the standing eight-count or the way boxers used to touch gloves before the final round. After the party conventions — according to my dad’s mythology — Americans took a break from politics in late summer, gathering at beach fronts or mountain getaways to soothe the national soul with Hamm’s beer and supermarket barbecue sauce. It was a tradition even scumbags and Republicans were obliged to observe.

My father didn’t live to see the advent of the two-year-long presidential campaign (conservatively speaking) or the endless regurgitation of political gossip on cable news, both of which I suspect he would have perceived as signs of tragic moral decay. In the last presidential campaign of his life, Michael Dukakis took the summer off, confident he had built an insurmountable lead over George H.W. Bush. That was surely the beginning of the end.

Even so, my dad couldn’t have imagined the election of a president who gleefully announced that there were no rules — in effect, that rules were for “losers” and “suckers” — and who was openly contemptuous of everything from the codes and norms of political discourse to the rule of law and the Constitution itself. If the world my dad was describing wasn’t exactly real, and had been conjured up to conceal certain uncomfortable truths about power and inequality, many Americans of his generation — and well after that — found its supposed rituals reassuring. That mid-century conception that politics was a manly, bare-knuckle brawl which nonetheless had clear rules of engagement is almost exactly what Joe Biden is selling in 2020.

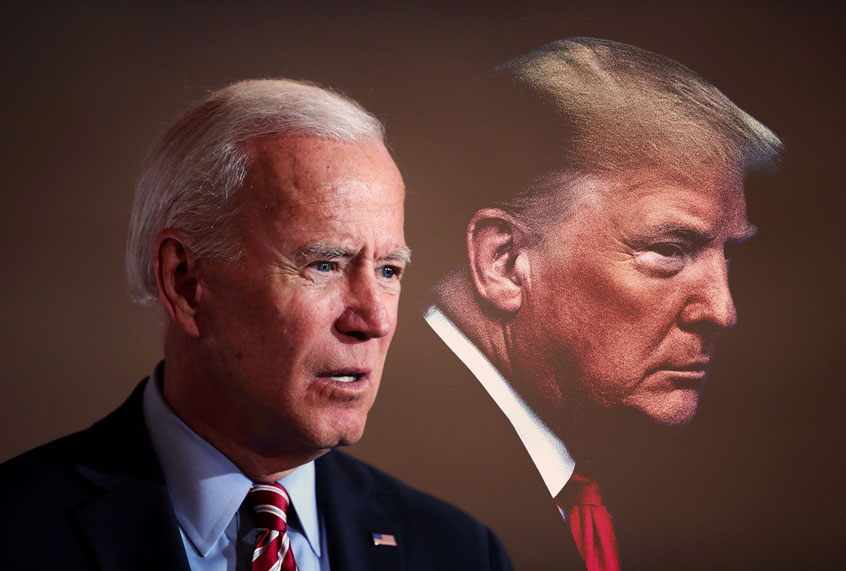

Biden has clearly been counseled to stop talking about a return to “normalcy” or about Donald Trump’s presidency as an “aberrant moment” in the upbeat tale of American progress, but that’s evidently what he wants and what he believes. It would be nonsensical to claim that the Labor Day holiday, in this year of all years, marks any meaningful launch or relaunch of the presidential campaign: We have known who the two nominees would be since older Democratic voters rallied around Biden’s flailing campaign in early March, and since then the Trump-Biden contest has unfolded in dramatic and intensely symbolic fashion, across a spring and summer that has seen nearly 190,000 Americans die and the largest outbreak of urban protests and rioting since the late 1960s.

Nobody in America got much of a break this summer, from anything — I don’t know how much “summer” you had, but I feel like I barely noticed it coming or going. Nobody reading this who has kids anywhere from pre-K to grad school needs me to tell them that the normal rhythms of fall are completely disrupted as well. But as that Times blurb I cited above makes clear, Labor Day in 2020 still signals an unmistakable shift, with eight weeks to go till Election Day. It has turned up the dread, the feeling of being caught in a repeating nightmare you can’t escape. Don’t tell me you don’t feel it.

For a great many Americans, probably close to a majority, this entire campaign has been driven by alternating currents of hope and fear. There is the hope that the corruption, incompetence, bigotry and unfocused evil of the Trump presidency can be replaced by something better, or at least by something less dire. There is the fear that an awful, gibbering darkness has been unleashed at the heart of our nation, and that the entire American experiment is being sucked into a downward spiral toward autocracy and self-destruction.

I could try to tell you — and in fact I believe this — that the choice between Trump and Biden in November probably isn’t the world-historical turning point it appears to be. (Either way, immense damage has been done that cannot be repaired anytime soon.) I can try to tell you — as I have previously argued, and still believe — that Trump is almost certainly doomed, and his recent behavior indicates that he knows that, after his own limited fashion. No incumbent president can plausibly survive this much bad news in anything close to a fair election, and if standard Republican-style vote-suppression tactics aren’t enough, Trump has neither the courage nor the institutional support to stage a full-on coup.

But dispassionate analysis aside, I won’t try to convince you that I don’t feel the dread, born of PTSD from the 2016 election and the reasonable or unreasonable terror — bordering on nightmare-scenario certainty — that it will happen again. The dread is real and it’s all around us, getting thicker with every twitch and flutter of the Pennsylvania polls and the London betting markets. Reason and logic cannot dispel it, both because dread by definition is impervious to those things and also because it was never reasonable or logical that Donald Trump would be elected president in the first place, and that event seemed to snap the tether that connected us to empirical reality.

In this fear-disordered view of the universe, Donald Trump does not appear to be a creature subject to reason or logic. He’s more like the demonic entity in a horror narrative — Cthulhu or Candyman or Freddy Krueger or Vigo the Carpathian — who gains more power over you, and becomes more real, the more you think about him.

If those fictional creations have cultural or psychological or perhaps even metaphysical explanations, so does Donald Trump. If they are best understood as bits and pieces of leftover diabolical theology, or as metaphors for mental illness — well, so is Donald Trump.

There is no question that Trump feeds on attention, positive or negative, and delights in the anguish and anxiety of his enemies. That’s been obvious from the beginning, when he rode down that now-legendary escalator and launched a campaign that was always more about speaking the unspeakable than about any specific ideas or proposals. But no one has been able to resist his hypnotic allure, and it does no good to blame “the media” or to claim that if the news networks hadn’t begun airing his campaign rallies live, the entire Trump enterprise would have dried up and blown away.

That was also a circular, “Call of Cthulhu” phenomenon, with no beginning, no ending and a magical, self-reinforcing quality. Media focused on Trump because the audience wanted more Trump, and in defiance of all known laws of the media universe, the more Trump they delivered, the more the audience wanted. Salon’s core readership officially despises Trump, of course, and I can testify after years of back-and-forth experimentation that it remains challenging to persuade them (sorry, that would be you) to read about anything else.

I’m not claiming that Trump does not exist, or that there’s no mathematical possibility he could be re-elected. If his 2016 campaign “drew to an inside straight,” to use the poker metaphor I’ve heard many times, and won an election in statistically improbable fashion, that unlikely event is no less likely the second time around.

I’m saying that Trump’s demonic power does not exist, or to be more precise that it’s something we invented — all of us, the media and the public, his fans and his haters — and vested in him, for mysterious but deeply troubling reasons. We have known from the beginning that Trump was a showman and a con man, doing a transparent act that all of us could see through, in different ways and from different perspectives. (His supporters delight in his performance, to be sure, but I have always believed it’s a profound categorical error to conclude that they’re a bunch of ignorant rubes who take the things he says literally.)

If Trump’s act “worked,” in the sense that he successfully devoured an inbred and decrepit political party and won a flukish, “inside straight” election, that happened because some of us desperately wanted it to and the rest of us desperately feared it might. That’s the Candyman-Cthulhu effect in action, or an illustration of the psychological truism that every fear hides a wish. The really difficult question America must answer, not just right now but over the long haul, is not whether or how we can make Donald Trump go away. The answer to that is obvious. The real question is why we needed him in the first place.