On August 20, 91 cafeteria workers at Yahoo (which is owned by Verizon) were abruptly told that their jobs had been terminated. In response, the labor advocacy group Silicon Valley Rising organized a protest on Thursday, in which they called for Verizon to continue paying subcontracted service workers during the shutdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Salon spoke with one of those former cafeteria workers, Agustina Sanchez, who with the help of a translator told Salon that she feels the government has not met its obligation to help the working class.

"I think it's a big responsibility and it's an obligation," Sanchez said. "It's a role that the government should play, to protect workers that are vulnerable, and we're all vulnerable right now. We're vulnerable to getting sick too. We need to be able to be supported economically because we have bills that we need to pay. We have rent. We need to make sure that we can support our families, and our children depend on our jobs and our wages that we have been able to count on."

Because the government has been reluctant to provide more than a meager amount of social support to those struggling during the pandemic, the question is whether organized labor movements can exert pressure on both state and private actors to enact basic social programs.

"Folks are waking up to the role that workers play," Maria Noel Fernandez, the campaign director for Silicon Valley Rising, told Salon. "And not just the workers that, for example, make up tech or engineers, etc., but workers as a whole — essential workers like the janitors, the security officers, the cafeteria workers, our grocery workers, our teachers." She argued that people are starting to see the important role that "those workers play in holding up our society. And so I think we're in a moment still where the labor movement has to continue to lift up those workers and fight like hell to make sure that those workers are protected, not just in pandemics and in this moment, but that we use this moment to shift how workers are valued in our country and our society."

Currently there is little documentation to indicate whether unions are gaining strength as a result of the various historic events in 2020 that would logically lead to that outcome — including the pandemic and forced shutdowns, mass unemployment and the resurgence of civil rights protests to oppose law enforcement racism. In January, shortly before the pandemic reshaped the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed that participation in labor unions had dropped from 10.5 percent of the American workforce in 2018 to 10.3 percent in 2019. By contrast, unions comprised 35 percent of the workforce in the 1950s, with even the non-unionized sectors benefiting as employers generally improved working conditions for everyone to stave off potential unionization.

This is not necessarily because Americans did not want to be involved in unions in 2019. Indeed, major strikes and protests in various sectors of the workforce made headlines, from unionized sectors like educators, auto workers and grocery workers, to non-unionized ones like gig economy workers at Uber and Lyft rallying for improved pay and working conditions. (Gig economy worker protests have continued through 2020.) Polls have found that nearly half of nonunion workers would join a union if it was possible to do so, and 64 percent of Americans supported unions as of 2019. Between 2017 and 2018, the number of workers who participated in large-scale strikes increased twentyfold, from 25,000 to 500,000. And the political careers of Democratic political candidates who explicitly and emphatically identify as pro-union — from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, who has become a prominent figure in the party, to Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who came within a hair's breadth of winning the party's 2020 presidential nomination — have been on the rise.

The problem is that, over the years, conservatives who have power in government have eroded unions' ability to succeed for the working class. The most recent example was the Supreme Court ruling in Janus v. AFSCME in 2018, in which union funding was decimated by a decision that prohibited labor organizations from requiring collective bargaining fees from public employees. There have been a number of successful conservative efforts to curtail union influence, from the infamous Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 to segregationists who rolled back unionization in the South by linking unions to the cause of civil rights. (There is indeed evidence that union membership makes people less racist.)

In addition, whenever the economy has taken a nosedive, workers have frequently accepted being hired at lower wages and without union protections because they become desperate to make a living. It is a toxic cycle: When fewer people are unionized, wages go down and it becomes more difficult for mass purchasing power to sustain periods of economic prosperity. As a result of the struggling economy, employers take advantage of working class insecurities to convince employees to not join unions and accept less than they need to lead comfortable lifestyles. This further exacerbates income inequality and leaves the economy more vulnerable than ever to setbacks, and so on.

"The US labor movement has been further exposed by 2020 events," Dr. Richard D. Wolff, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told Salon by email. "Divided, hesitant to act publicly and militantly organized labor is now less socially influential than ever across its long decline since the 1950s. Business and the government it controls undid or rolled back the successful labor organizing drives of the 1930s and the New Deal they won." Wolff's reference to the New Deal involves how, as a result of the economic devastation caused by the stock market crash in 1929, a period known as the Great Depression occurred — and with millions of Americans suffering from unemployment and poverty, unions became stronger than ever, with President Franklin Roosevelt eventually becoming one of America's first leading pro-union politicians.

"With unemployment now akin to that of the 1930s, we do NOT see the labor militancy that made US history back then," Wolff explained. "There are sparks of that militancy — the professional athletes, the professors, the fight for $15, and so on -—but they now happen more outside than inside organized labor unions. If organized labor faces its failures and faults and commits to work with today's militants for social change — as unions did in the 1930s — it can again play a leading role now when the working class needs organization and leadership more than ever."

Jake Grumbach, a political scientist at the University of Washington, had a somewhat more optimistic outlook.

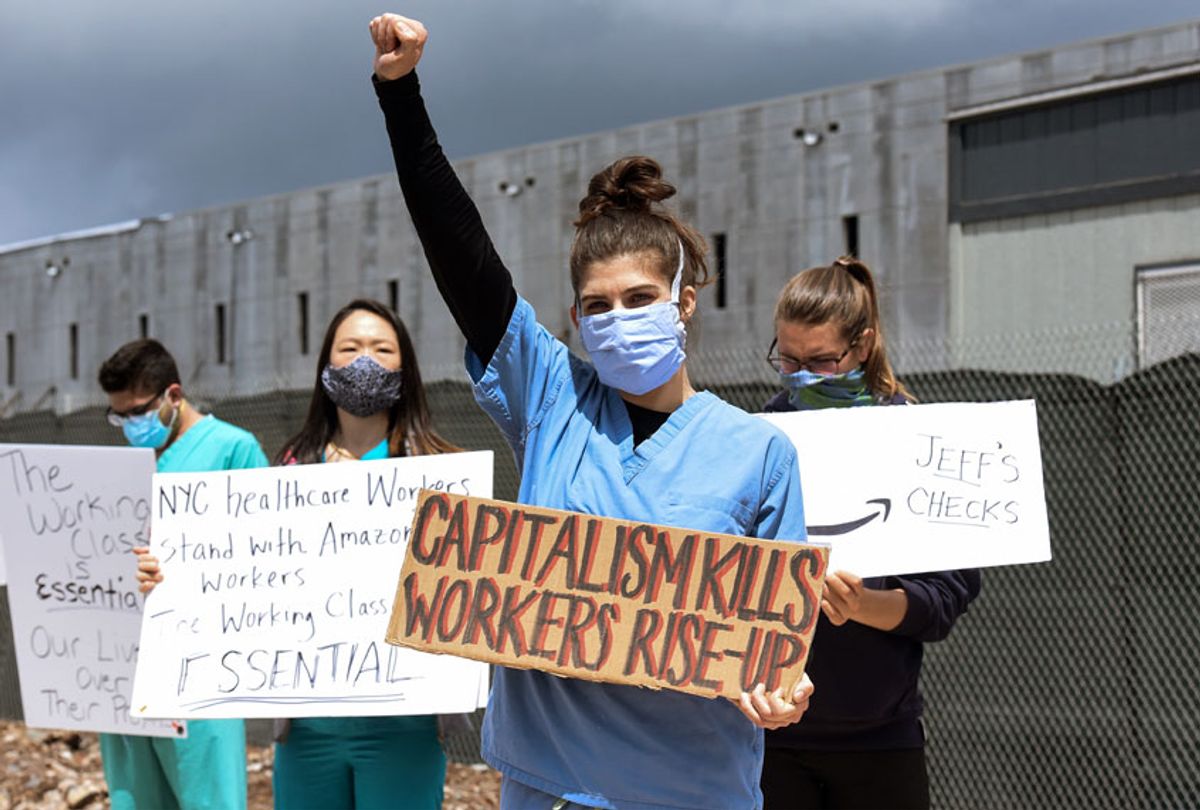

"2020 has been a transformative year for the US labor movement," Grumbach wrote to Salon. "The pandemic has highlighted a fundamental disconnect: workers are 'essential,' but are undercompensated and given few rights in the workplace. This has led workers and activists to grow skeptical of symbolic gestures and empty praise, whether at the workplace or in the Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality. Strikes and protests have been on the rise."

He added, "The protests in response to the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor may be the most widespread protest movement in American history. And on the heels of the teachers strikes of 2018 and 2019, NBA players began a wildcat strike in response to the police murder of Jacob Blake and so many others. 2020 has shown that Americans who care about labor and racial justice can use their people power in protests and strikes to disrupt the status quo."

Paul Frymer, a professor of politics at Princeton University, told Salon by email that "on the one hand, bad economies can weaken the leverage of unions because of higher unemployment and layoffs, and the risk of future job loss. On the other hand, being unionized right now is more vital than ever as it protects otherwise vulnerable workers from job loss. And, as we are seeing with teachers unions, teachers with contracts are able to ask for and receive protections from COVID health concerns that non-unionized employees would struggle to receive."

Like Wolff and Grumbach, he also pointed to the Black Lives Matter protests as an example of effective unionization in 2020, noting that "the NBA players are exemplars, but they are not alone, as union members from across the country have walked out for BLM with the protection of union contracts that prohibit being fired for political protest (according to an NLRB advisory memo of 2018 which protected workers from striking the year before on behalf of immigrant rights during the 'Day Without Immigrants' protest.)"

This is not to say that unions are entirely without their flaws. One of the few unions that still has considerable political clout — police unions — have become a bulwark against police reform. Studies have shown that police unions use their power to protect violent and racist officers from disciplinary consequences, often making it possible for officers to stay on the force after multiple complaints of abuse have been filed against them.

"Measures that discourage accountability vary by jurisdiction, but typically include some combination of collective bargaining agreements, civil service protections, a Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights and discrete legislative statutes," Jill McCorkel wrote for Salon in June. "Taken together, they afford police greater procedural safeguards than citizens suspected of a crime have and offer more employment assurances than are available to other public servants. They also make efforts to deter brutality and corruption all but impossible."

At the same time, as a recent report by the Brookings Institute makes clear, unions are more essential in the COVID-19 era than ever before. Unemployment has been stuck above 10 percent since April, meaning that Americans who have jobs need protection against losing them and those who do not need guarantees that joblessness won't lead to impoverishment. As many employers pressure their workers to return to their physical locations of employment, the common lack of PPE (personal protective equipment) and other materials and rules which could keep them safe is striking.

If Labor Day is to be more than empty gesture, Americans will need to internalize its underlying lesson. Without unions, the American working class will not receive the protections to which it is entitled in order for its members to lead a decent quality of life. This was true before the coronavirus pandemic, but is particularly striking in 2020 as a result of it.

Shares