It's been said that the United States hasn't seen comparable social upheaval since the civil rights and anti-war struggles of the sixties and seventies. Yet as the racial justice protests of today make apparent, the civil rights movement of then was an unfinished project: indeed, we may not be in the situation we are now, the virus of racism still infecting our nation, if the counterculture movement had been as culturally and politically effective as we'd like to imagine.

What went wrong, and what went right, are key to understanding the future of any social struggle. And my generation and the adjacent one— meaning millennials and Zoomers — are the most apt to be politically active, by dint of how viciously our lives are affected by today's political turmoil. Unfortunately, none of us were alive to witness what life was like back then, which makes it difficult to understand today's social movements in historical context.

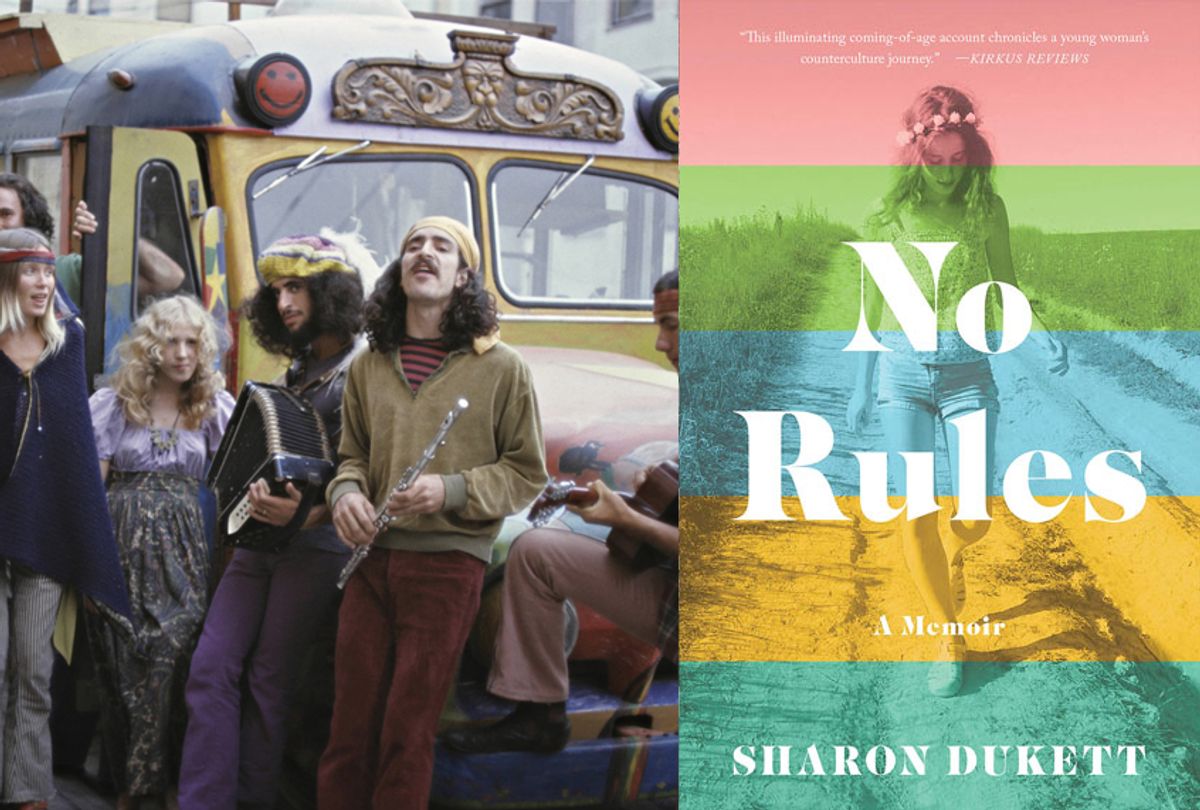

This is partly what makes Sharon Dukett's memoir, "No Rules," so engrossing. Dukett's journey epitomized the mantra "tune in, turn on, drop out": as a teenager, Dukett literally dropped out of high school, motivated by a rare chance to live on the other side of the country beyond the grip of her parents. She quickly became immersed in the free-spirited hippie world of protest, drugs, love and music. "No Rules," like all great memoirs, grants the reader the feeling of time travel — immersing you in the body of someone who was there to witness a now-alien era. Though I'd like to think of myself an informal scholar of that era by virtue of my family's background, Dukett's honest and vivid book gave me the first real understanding of what life was like then for one of the hoi polloi: Dukett, a teenage runaway, couldn't easily fly home if things went awry.

Thus, Dukett didn't navigate the counterculture with considerable privilege. Men mistreat and abuse her and those in her vicinity, authority figures harass she and her friends, she observes evictions, experiences homelessness, and people in her circle even die. Hers is a bottom-up, rather than a top-down, view of the life of a young person then.

I spoke to Dukett over the phone about her memoir, and what lessons the counterculture movement has for youth political culture today. As always, this interview has been condensed and edited for print.

I always wondered what it would be like live back in the 1960s and 1970s, but most of the accounts you read are from the famous people of the time — people who have more power and agency than you did. I guess, like, Hunter Thompson or Joan Didion or something like that.

Yes, not just the average person-on-the-street kind of thing.

Exactly. I guess that's one of the things I really I found so vivid and fascinating about the book. You weren't somebody who was taking a lead role in, say, storming People's Park or something. You were just living in the time, and the people you encountered and the music you saw and protests you attended were just a cross-section of the time period.

My daughter-in-law actually read it also — I had her proof read and she read it. She's 28, and she had kind of the same reaction. Her and my son talked about it, and one of the things they talked about was how, first of all none of these things could happen today, just because of the way everything is so different. You couldn't do this stuff, you couldn't get away with these things. They found that really fascinating.

I agree. Although one thing I found surprising, that maybe hadn't changed, is how you describe the gender relations between straight people in the book — the way that the men treated you, or often abuse you — it reminded me a lot of young men nowadays who are mistreat women or gaslight them. There's something that hasn't changed there that I thought was really telling and foreboding. Do you think that, maybe in some ways, things haven't progressed?

I think it kind of comes and goes. In general I find, just judging from my sons and their friends and so forth, there's a lot more of an open attitude towards what are the male and female roles and who does what, and all that sort of thing. I think that has changed to a certain degree, but I'm probably not in a position to judge from the perspective of sexuality how that has changed since it's not part of my perspective. Although I did notice with my children growing up that a lot of things had changed. The one thing that I found amusing though was one of my sons said something about some girl giving him her phone number, and so he was going to call her, and he goes, "No, I'm going to wait for her to call me." I was like, really? He's like, "Oh yeah, they all call you now." I found that sort of different.

It seems like a lot of your story starts with your parents' expectations of you. They didn't really want you go to college —

Right. They didn't see the point.

Do you feel like that was something you were sort of working through, that may have led to your desire to run away from them?

It definitely influenced how things went. I'm a pretty intelligent person and, had I been going to college like some of the other people that I went to school with, I probably would have been more focused on staying in school. Of course at that point I wanted to [go to college] — my motivation around college was more to be out there with the people who were protesting and that kind of thing, where everything was going on. But nonetheless, people who did that still did manage to get an education at the same time. I did feel like I belonged in college, because a lot of my friends were college bound people. Then when it became clear to me that wasn't where I was going, I kind of had a split with my parents.

From there, I lost motivation. I just didn't see the point at that age. What was school going to get me? This life that was awful, that I didn't want to live.

One of the other things in the book that I've been struggling to wrap my head around is this character you meet briefly, Steve, in the bar in Montreal. He seemed like he had PTSD. As you recount, he had been hitchhiking with his girlfriend, and rednecks had stopped them and beat him up and raped his girlfriend in front of him. The way you depict him he's clearly dealing with the trauma from that.

What I found so shocking was the idea that somebody would be subject to so much violence simply because they look like a hippie. Nowadays, most discriminatory violence is either gendered, racial violence, homophobic, transphobic — but like, to think that someone would beat me up because I wear tie-dye.... it's just hard for me to fathom someone looking at me and being like, "Oh, you're wearing patchouli, I'm going to beat you."

I mean, in a way you can see that nowadays if you think in terms of the extreme right and some of these people walking around with the AK-47s in the capital and stuff — like, who are calling liberals all sorts of horrible names. The only difference then is walking down the street you could tell who were liberals and the conservatives because they dressed differently, they looked different. Not with everyone I guess, but certainly if you were a hippie, you were pegged as liberal, and therefore you could be picked on as a hippie — versus if you had a crew cut. It was pretty clearly laid out who was who in that respect and a lot of that.

Where it got blurry was with the Vietnam vets returning. They tended to be more, what you would think of today, as a lot of people in the military — they tended to be more right-leaning, but still they kind of blurred in and mixed in with the hippies in a lot of cases. Not all cases but there was a number of them that did.

Of course it was different back then too because people in the military, a lot of them didn't want to be in the military. They were there because of the draft, so you had all kinds of people in the military.

I guess the bigger question I'm leading to was to ask you about political differences between then and now. In some respects, it seems like the hippies won a lot of the cultural wars — say, in terms of pot being legal, and that multiculturalism is a normalized positive concept — but on the other hand, we're a very divided country now. We don't have a draft anymore, but we just use poverty as a draft. Likewise, I think Donald Trump and George W. Bush were both the antithesis of the '60s sentiment as far as leaders go. I was wondering what you kind of thought about the unfinished cultural revolution of that era?

Yeah, it's frustrating that a lot of the progress that seemed to be made during that time, in the beginning of things that became progress, seemed to have reversed. Abortion's a real big one, too. One of the things that did start, I think especially among the back-to-the-land people, is the whole idea of food being organic, and getting chemicals out of the food, and all that sort of thing. That has taken a strong hold, and survived the culture and grown and gotten more significant.

It's strange because I think our culture now, in a lot of ways, is much more liberal — and yet much more conservative. It was pretty polarized back then too. It was hugely polarized in a lot of ways.

Then we went through a period where things seemed to get more close and more progressive, and then now we're going back towards polarization again. Well, not "back to" — we're in the midst of it. One of the things I found interesting about that era is that among the hippies there weren't any clear lines of economic breakdowns. Rich people and poor people could all be hanging out together — and while I didn't commonly come across many black hippies, I know that depending on where you were, it wasn't unusual for black people and white people to also all be hippies and be hanging out together, although maybe less so. Those kinds of lines were breaking down. But then it didn't continue for people in the poorer classes, and I sense that in a lot of places people are still somewhat segregated today, too.

I was going to ask you about the class thing, too. You met so many people doing the same thing you were doing — hitchhiking and traveling across the US, and Canada. Did you get a sense that the people who were maybe hitchhiking on their own were from the less well-off families, or more conservative families had rejected them? Or did it just seem like there wasn't really a logic to it?

Well, I think it depends. In the summertime, it was hard to tell because of course people were out of college or people were moving around and that kind of thing. When I lived in the commune three of the people who lived in the commune were Cornell graduates. The commune was near Cornell and it had kind of spun off from people who knew each other who had gone to Cornell. I was there and Jodi was there, and Jodi was a high school dropout at that point in time. Then there was another guy who came from a lower income, so it was really a mix of all kinds of economic backgrounds of people who were living in this commune. We kind of found that from place to place.

There's a lot of scenes in here of you seeing the music of the time. Did you feel like musical culture has changed a bit now, or that you got to experience and be part of something special by the musical scene of that era?

Well, I think music [back then] really had a message in a lot of cases — and I don't know if you have as much of that going on now. And plus, I think because there's so much access to music now, there's less concentration on certain bands, or whatever that are big names. It seems more ... it's very hard for me to even keep track of what new music is around, and it's all out there which is great but I don't know. I know it's very hard for musicians. I follow David Crosby on Twitter and he talks a lot about how hard it is to make a living as a musician nowadays which is really unfortunate, even for him.

Do you feel like people are more politicized now? I'm thinking how, when I was in high school, I knew people who said "I'm not political." I'm not sure anyone would say that now. What about then?

Yeah, because politics affected your life directly. Whether you were going to be drafted or not was huge. You couldn't avoid it. Maybe if you were an older person — which I wasn't — if you were in your thirties or something, maybe it was easier to feel that way where you didn't have children who were of that age, and your children were little or something.... maybe then you could avoid thinking about those things.

What do you think made so many people of different creeds unite then, and feel such camaraderie? Was it partly the draft, in that it was a semi-universal experience, at least for anyone who was a young man or knew a draft-age man?

Yes, though I think a lot of that is going on right now — it's just that, it's not as focused. Certainly that's the kind of thing you were seeing around the Bernie Sanders supporters, the younger people.

Maybe it's just crisis that makes people unite — although oddly, this whole coronavirus thing is kind of strange, in that it started out with people being united, and now it's turned into people splitting again. I think there are political powers working to make sure that happens. Unlike a situation, say, with 9/11, when the country was probably as united as it ever was.

Sharon Dukett's memoir, "No Rules," is out now from She Writes Press.

Shares