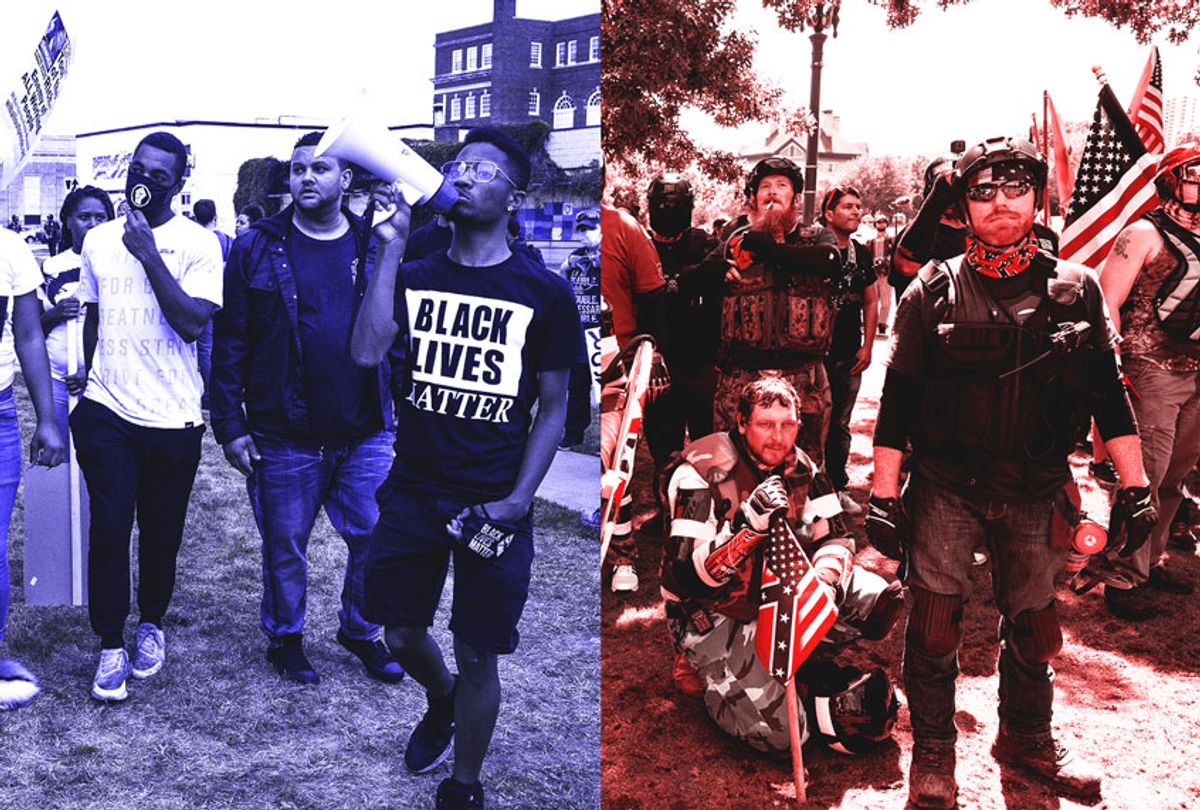

The tinder that could soon ignite widespread violent conflagrations throughout the United States lies ominously stacked around us. Millions of disenfranchised white Americans, who see no way out of their economic and social misery, struggling with an emotional void, are seething with rage against a corrupt ruling class and bankrupt liberal elite that presides over political stagnation and grotesque, mounting social inequality. Millions more alienated young men and women, also locked out of the economy and with no realistic prospect for advancement or integration, gripped by the same emotional void, have harnessed their fury in the name of tearing down the governing structures and anti-fascism. The enraged, polarized segments of the population are rapidly consolidating as the political center disintegrates. They stand poised to tear apart the United States, awash in military-grade weapons, unable to cope with the crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout, cursed with militarized police forces that function as internal armies of occupation and de facto allies of the neofascists.

The spark that usually sets such tinder ablaze is martyrdom. Aaron "Jay" Danielson, a supporter of the right-wing group Patriot Prayer, was wearing a loaded Glock pistol in a holster and had bear spray and an expandable metal baton when he was shot dead on Aug. 29, allegedly by Michael Forest Reinoehl, a supporter of antifa, in the streets of Portland, Oregon. A woman in the crowd can be heard shouting after the shooting: "I am not sad that a fucking fascist died tonight." On Thursday, Reinoehl, allegedly armed with a handgun, was shot and killed by federal agents in Washington state.

Once people start being sacrificed for the cause, it takes little for demagogues of the radical left and the radical right to insist that self-preservation necessitates violence and is a prerequisite for victory.

Violence is a narcotic. It fills the emotional void. It imparts a feeling of godlike omnipotence to the powerless. It instills feelings of comradeship and belonging to the alienated. It gives to social outcasts, crippled by humiliation and rejection, a sense of meaning and higher purpose. It obliterates the despair that once defined their lives and replaces it with feelings of ecstatic self-importance and self-adulation, a state of being outside the self. The world suddenly becomes a Manichaean battleground between them and us, the forces of dark and the forces of light.

When I wrote "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning," a reflection on the culture of war after two decades as a correspondent in Central America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans, I meant it. I have seen this dark elixir at work in other disintegrating societies. I know too intimately the rush that violence engenders, the overpowering lusts that seize a mob or armed unit when it destroys, even human beings, and the heady attraction of suspending all personal morality and individual responsibility for the wild intoxication of violence. It is the absence of empathy, perhaps the best definition of evil.

The words left and right, once violence becomes the primary form of communication, are meaningless. These are death cults. They venerate and worship death. The martyrs justify the murder of the enemy, including the detested voices that call for understanding, reconciliation and nonviolence. To suggest anything other than the total annihilation of the enemy — and the enemy includes all who do not fully and uncritically support the cause — is apostasy. It is the dead who rule. Their voices cry out from beyond the grave demanding vengeance and new heroes and martyrs to take their place. There are constant and repeated acts of remembrance for the fallen.

This cult of the dead is integral to combat units in the military. Those who attend the Ranger Assessment and Selection Program, an eight-week course held at Fort Benning, Georgia, to become an Army Ranger must select a "Ranger in the sky" who was killed in action. Recruits, who are warned not to pick former NFL player Pat Tillman, are required to know the details of the dead Ranger's personal life before enlistment and his military career. They must carry this information on a piece of paper with them at all times. It is an inspectable item. Idealists, seeking to lift themselves up from the depths of social obscurity and be fêted as heroes, become, whether as Army Rangers or members of violent militias, willing sacrificial victims. But as deaths accumulate, these martyrs, once so important and precious, disappear into faceless, nameless piles of corpses.

The Nazi Party in 1930 found its primary martyr in the 19-year-old Brownshirt Horst Wessel, who led a branch of the Nazi paramilitaries that attacked Communists, especially those who made up the rival Communist militia called the Red Front-Fighters' League (RFB). Wessel was shot dead by Albrecht "Ali" Höhler, a Communist militant and petty criminal — later assassinated by the Nazis — after a complaint was made to the party about Wessel by his Communist landlady. Wessel instantly became a "martyr for the Third Reich." The "Horst Wessel Song" became the official anthem of the Nazi Party. Fascist and Communist violence, with deaths on both sides, exploded in the streets of Weimar Germany in the early 1930s. The mayhem, much of it instigated by the fascists, eventually exhausted the German public and made it susceptible to the right-wing and fascist promises to impose law and order.

Martyrdom also played a central role in the eruption of the war in the former Yugoslavia. On March 1, 1992, a wedding procession of Bosnian Serbs in Sarajevo was attacked by Ramiz Delalić, a career criminal and a Muslim known by his nickname, Ćelo. The father of the groom, Nikola Gardović, was killed. A Serbian Orthodox priest was wounded. The shooting of Gardović, like that of Wessel, was used by Serb nationalists to whip up a blood fury. It saw Serbs erect armed barricades and roadblocks throughout the city, and led not long afterwards to a war in which most of Bosnia was destroyed, 2.2 million people were displaced from their homes and at least 100,000 died.

I watched many funerals in Gaza for Palestinian martyrs. They were little more than recruiting ceremonies for militants and suicide bombers. A truck with a generator in the back and huge loudspeakers on the cab would be at the head of the funeral procession. The speakers would blast out verses from the Quran, along with slogans calling on heroes to fight and die for Palestine and become a shaheed, or martyr. Young boys would run alongside or behind the truck. The funeral processions made their way slowly down the dusty, narrow streets of the refugee camps, past the concrete hovels, the walls decorated with pictures of the newest martyr or murals that depicted past attacks, such as a bus with the Israeli Star of David on it being consumed in a fiery explosion. "Don't be merciful to those inside," the Arabic script read below the picture of the bus. "Blow it up! Hit it!"

"It is the first death which infects everyone with the feeling of being threatened," wrote Elias Canetti, a Bulgarian refugee from Nazi persecution, in "Crowds and Power":

It is impossible to overrate the part played by the first dead man in the kindling of wars. Rulers who want to unleash war know very well that they must procure or invent a first victim. It need not be anyone of particular importance, and can even be someone quite unknown. Nothing matters except his death; and it must be believed that the enemy is responsible for this. Every possible cause of his death is suppressed except one: his membership of the group to which one belongs oneself.

The flashing red lights are all around us. Joe Biden and the Democratic Party will do little to restore the social bonds or address the social inequality and disenfranchisement of tens of millions of Americans, now facing evictions and bankruptcy, which is fueling the social collapse. Donald Trump and the Republican Party, along with media outlets such as Fox News, in a bid to retain power, are fanning the flames of violence, seeing in the incitement of far-right mobs a route to a ruthless police state.

In armed conflicts, facts and truth no longer matter. Lies, if used to further the cause, become righteous. Truth, if it hurts the cause, is blasphemy. If your side commits an atrocity, it's justified by an atrocity, real or invented, carried out by the enemy. The ends always justify the means. The moral universe is banished, replaced by a self-serving pseudo-morality.

"In the beginning war looks and feels like love," I wrote in "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning":

But unlike love it gives nothing in return but an ever deepening dependence, like all narcotics, on the road to self-destruction. It does not affirm but places upon us greater and greater demands. It destroys the outside world until it is hard to live outside war's grip. It takes a higher and higher dose to achieve any thrill. Finally, one ingests war only to remain numb. The world outside becomes, as Freud wrote, "uncanny." The familiar becomes strangely unfamiliar — many who have been to war find this when they return home. The world we once understood and longed to return to stands before us as alien, strange, and beyond our grasp.

Shares