“Hey, let’s check our social calendar. Nothing, total blank.” This line reads like a moody tweet that any of us could have sent last night. Or the night before — or, frankly, anytime since a global pandemic was declared in early March. But it’s actually the first line of a 1994 episode of the CBS comedy-drama “Northern Exposure,” delivered by disc jockey Chris Stevens (John Corbett) to the residents of the fictional town of Cicely, Alaska.

The town isn’t in the midst of a viral outbreak, but they are experiencing their annual “solar drought,” the two months of the year when there is only an average of an hour and a half of sunlight a day. The freezing temperatures are brutal, and the darkness is isolating.

“It’s cabin fever season people, that time of year when four walls feel like they’re going to come in here and choke the spirit right out of you,” Chris says. “Time to lock away those firearms and hang tough. No way through it except to do it.”

The first time I watched the series a couple years back, those lines didn’t leave much of an imprint. My boyfriend had methodically bought up seasons of the show as the DVDs came available on eBay and Amazon (the series, unfortunately, isn’t currently streaming anywhere), and we leisurely watched them, several episodes at a time, over the Christmas holiday; but that bit of dialogue definitely hits differently after months of quarantine.

So, too, does the entire show. Thirty years after its premiere, it’s a balm for social isolation, with its gentle interrogation of the ways in which myth, folklore and fantasy inform our internal lives — and what happens when we eventually take those parts of ourselves out into public again.

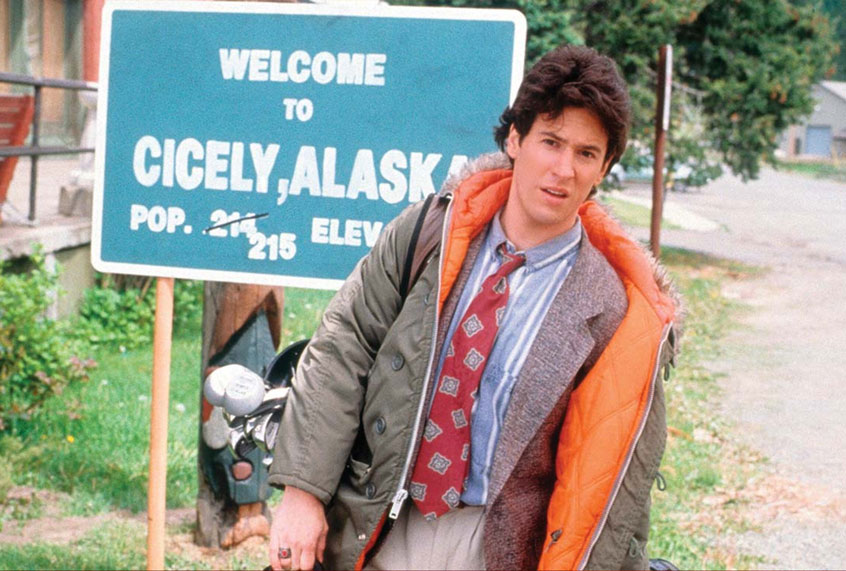

The series opens as a typical “fish out of water” story. Dr. Joel Fleischman (Rob Morrow) is a neurotic New York City physician who applied for a state-run scholarship program that would pay his tuition expenses if he agreed to be stationed in Alaska post-graduation. Initially, he’s supposed to take a residency in Anchorage, but he ends up in Cicely, a very remote fishing village just at the edge of the wilderness.

The culture shock narrative helps drive the show’s first season — the man just wants to know where to get a good bagel! — and guides Joel’s interactions with the town members, all of whom vary in their eccentricities. In the daily rotation, there’s ex-astronaut and millionaire Maurice J. Minnifield (Barry Corbin); bush pilot Maggie O’Connell (Janine Turner) who has a string of former boyfriends who have died in freak accidents; beauty pageant winner Shelly Tambo (Cynthia Geary) and her much-older — by 44 years — boyfriend Holling Vincoeur (John Cullum), a hunter and bar owner who was born in the Yukon; Ed Chigliak (Darren E. Burrows), a young Native American man who is sweet, but a little hapless, and dreams of becoming a documentary filmmaker; and Chris Stevens, the local DJ, conceptual sculptor and de facto town philosopher.

As in a lot of shows about remote small towns — from “Green Acres” to “Schitt’s Creek” — Cicely seems to exist in a universe all its own, built on unique traditions and around its inhabitants’ idiosyncratic personalities. This sense of singularity served as an ideal foundation for some of the show’s more surrealistic turns.

Joshua Brand, co-creator of “Northern Exposure” was once quoted as saying, “We used Alaska more for what it represents than what it is. It is disconnected both physically and mentally from the lower 48, and it has an attractive mystery.” As such, fact and fiction blend in “Northern Exposure,” and Joel’s initial culture shock, which propelled the show, soon morphs into a kind of dreamy discourse on the topics of personal and communal discovery.

It’s not a shock that David Chase, who served as a showrunner on the series’ final two seasons, eventually wrote and produced “The Sopranos,” which used similar dips into surrealism and dreams to show-stopping effect in episodes like “Join the Club” or “The Test Dream.” There are also obvious parallels to the magical realism in “Twin Peaks,” which debuted the same year as “Northern Exposure,” though is decidedly darker in tone. (Fun fact: The fifth episode of “Northern Exposure” pays tribute to “Twin Peaks” in a dream sequence.)

On “Northern Exposure,” there are entire episodes in which the action that takes place is contained wholly within Joel’s mind, like when he ingests a Native American herbal remedy and is mentally transported to an alternate New York, filled with wildly different versions of the town members. There are also episodes where the distinction between fantasy and reality is blurred, like when Joel bumps his head in an early episode and has fantasies about “Jules,” his good-for-nothing twin who shows up suddenly in Cicely. Is Jules real? Probably not literally, but he’s definitely a part of Joel (something that I think Freud, who shows up in a jail cell in this episode, would have thoughts on).

There are characters who are on decidedly more intentional spiritual journeys. Ed, who was abandoned by his mother when he was a newborn and raised by the Tlingit tribe, knows that there is a world outside of Cicely — it’s revealed that he’s apparently pen pals with Woody Allen, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese — but doesn’t quite know how to reach it. He seeks help from his spirit guide, from One Who Waits (played by Floyd Red Crow Westerman, and who is invisible to almost everyone but Ed) and eventually begins to train to become a shaman.

Meanwhile Chris, who spends mornings on-air waxing poetic about topics ranging from Carl Jung to motorcycle repair, is constantly evaluating his own metaphysical connections. One of my favorite examples of this from the series is found late in the fourth season, simply titled “Revelations.”

“Hey folks, I’ve just come back from a short cruise on the river of spiritual renewal,” he says on the radio. “You might be wondering, were my goals met? Did I have that transcendent moment, the epiphany? You bet I did.”

Over the course of the episode, we watch as Chris attempts to find his “innermost secret center” while spending time at a monastery. While there, he thoroughly enjoys his sparse surroundings — until he finds himself overcome by lust for one of the resident monks. Meanwhile, Joel becomes restless after being without a patient for two weeks; he doesn’t know how to sit still, and the residents attempt to teach him. The contrast between the two men is striking, and endlessly relatable, both then and now.

That’s what makes “Northern Exposure” so enduringly poignant.

In the town of Cicely, there are very few people that are portrayed as just straight-out bad. Egotistical or exasperating? Sure, but at this show’s center is an understanding that we are all just human and, as such, are just trying to get by. We do that in different ways — reminiscing about our days in space, delving into the works of the literary greats, dreaming about the days that we can have something again that we once thought was a give, like a good bagel.

“The ‘nonjudgmental universe’ [of ‘Northern Exposure’ ]isn’t just about acceptance,” wrote critic Brian Doan in his remembrance of the show on its 25th anniversary. “But an openness that allows people the space to be screw-ups, to be selfish, and annoying, and paradoxical at every turn.”

And when we are isolated from one another, either through solar drought or global pandemic, it’s easy to grow restless, much like Joel did again and again while transitioning from the big city to Cicely. But, of course, Chris had something to say about that. In the first season’s third episode, he tells Joel that it’s okay to ground himself in the present, without thinking about what used to be or what’s on the horizon.

“The way I see it, if you’re here for four more years or four more weeks – you’re here right now,” he said. “You know, and I think when you’re somewhere you ought to be there, and because it’s not about how long you stay in a place. It’s about what you do while you’re there. And when you go, is that place any better for you having been there?”