With both parties' conventions behind us as we head into a quasi-apocalyptic election, there's more need than ever for a sense of balance. Not the kind of false balance that equates truth with lies, or soothing psychological balance that lulls us with a false sense of security, but rather a balanced sense of history and political possibility that helps us understand where we're going, and why. Understanding America's real history is particularly important, as shown in Nathan Kalmoe's new book, "With Ballots and Bullets: Partisanship and Violence in the American Civil War," as discussed in our recent interview.

But there was another time, long before the Civil War, when America threatened to come apart — and believe it or not, it was New England, not the South, that threatened to secede. That largely forgotten episode was entwined with a longer forgotten history: How religious freedom, once it was established in the U.S. Constitution, finally triumphed over theocracy in the intransigent state of Connecticut (as implausible as that may sound today). That story is told in a new book by author and researcher Chris Rodda, "From Theocracy to Religious Liberty," which uses contemporary sources to trace the narrative that led from Thomas Jefferson's famous 1802 letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, to a state constitution that enshrined religious liberty.

What a story it is! It's a tale of two clashing partisan identities that's strikingly similar to our world today, especially as Rodda describes the "Party of God," circa 1800:

The Federalists, like today's Republicans, were the conservatives, the party that believed the rich should rule, feared that more people being able to vote would put them out of power, regarded immigrants with contempt, and hypocritically boasted of having "all the religion." The Federalist clergy, like the right-wing clergy of today, were outspokenly political, preaching that it was a religious duty to vote for Federalists.

The Federalists may not have had social media in the contemporary sense, but they definitely had viral memes, vicious rumors and conspiracy theories, often ruthlessly spread by the men in the pulpits of the largest and most powerful churches. Of course, they had voter suppression laws too. Arguably they had far more in common with us than contemporary Americans have with our own recent history — at least back when we still had the FCC's "fairness doctrine" ensuring some degree of balance in major media.

So the story of how Connecticut moved from a colonial-era theocracy to a modern pluralistic democracy is more than a historical curiosity. It's a source of inspiration and instruction for all of us in the midst of our own very dark time. There is light ahead, if we make it so. It's been done before. For a sense of its whole sweep, Salon interviewed Rodda by email. Our exchange has been lightly edited.

Thomas Jefferson's letter to the Danbury Baptists is famous for the phrase "wall of separation between church and state," but while that wall existed at the national level, it didn't exist at the state level in Connecticut, which was a theocracy ruled by the Federalist Party. What did this look like at the local level? How did religion and politics intermix?

Religion and politics were completely intertwined. As the Danbury Baptists wrote to Jefferson, "religion is considered as the first object of legislation." The ruling Federalist party and the established clergy operated as one big machine. The clergy were financially supported by the Federalist government, and in return the clergy preached that it was a religious duty to keep the Federalists in power, and also attended their towns' elections to deter anyone from voting against this "standing order" of Congregational Federalists.

The established religion was a combination of Congregationalism and Presbyterianism called the Saybrook Platform, named for the town of Saybrook where, acting on an order from the legislature in 1708, the colony's Congregationalists and Presbyterians held a synod to form one church system for the colony. Everyone in the state was assumed to be a member of this established religion, and taxed to support it, unless they filed a certificate with the clerk of their town's established church to be able to join a dissenting church. In their letter to Jefferson the Danbury Baptists described this as degrading. It marked the dissenters as second-class citizens.

To give you an idea of the effect of this certificate law, when Connecticut finally held a constitutional convention in 1818, one of the delegates recalled that as a boy it was the cause of many bloody noses, with kids from the established church teasing the kids whose families had "certificated off," as it was called.

How did the Federalists describe themselves, and how did the Republicans criticize them?

The Federalists sounded a lot like today's Republicans. They boasted of having all the religion, and were the party of law and order. The Democratic-Republicans, who I'll just call Democrats since that's what the Federalists called them, constantly called out the Federalists as hypocrites, liars and conspiracy theorists, which were all well-founded charges.

What argument did the Federalists make to attempt to maintain their power?

The Federalists, again not unlike today's Republicans, used a combination of fear-mongering and history. Their theocratic form of government was how things had always been, and to change anything instituted by their wise and pious forefathers would lead to all manner of vice and chaos. If, God forbid, the Democrats ever got into power, all religion would be abolished, and even the institution of marriage would be abandoned. It would be just like the French Revolution's reign of terror. There would be blood in the streets, Bibles would be burned, churches leveled to the ground, and the clergy driven from their pulpits or even killed. Just think of Trump talking about Democratic mobs destroying America's history and you'll have an idea of the tone of it.

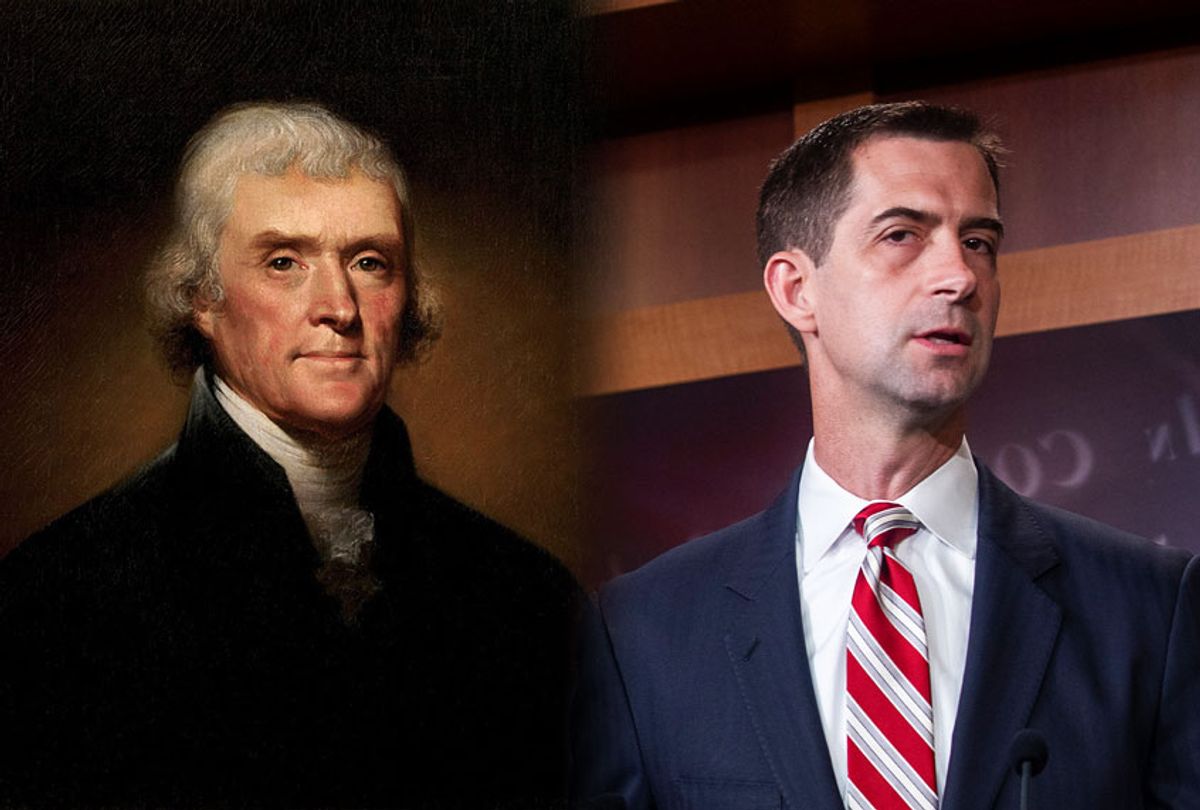

In fact, a Republican senator, Tom Cotton, recently said of today's Democrats on the Senate floor, "They've adopted the spirit of a Jacobin mob in the French Revolution. A reign of terror, trying to completely erase our culture and our history. Unfortunately many Democrats are vying to be the Robespierre for this Jacobin mob. Are we going to rename the Washington National Cathedral the Temple of Reason, as the Jacobins did to Notre Dame during the French Revolution?" Those words could have come straight out of a Federalist newspaper in early 1800s Connecticut.

Power was even more concentrated at the state level, where there was no separation of powers. How did that work?

Unlike the other states, with the exception of Rhode Island, Connecticut had not written a state constitution at the time of the Revolutionary War. Instead it retained its 1662 charter from King Charles II, and the laws made under the charter, as its form of government. As things were, a 12-member council was both the state senate and its highest court, and also appointed judges. So there was no separation of powers between the legislative and judicial powers. The governor had no veto power, so there was no check on the legislature by the executive. And the governor also presided over the high court, leaving no separation of powers between the executive and judicial branches. The council, in effect, held all the power. With a majority of seven council members having the sole power to approve or disapprove any act passed by the lower house, and election laws making it impossible for any non-Federalist to get elected to the council, seven Federalist lawyers perpetually ruled the state.

The election law was quite restrictive, and was made more restrictive after Thomas Jefferson won the presidential election of 1800, with what was known as the "Stand Up Law." How did that work, and what was its purpose?

The election of Jefferson, and the organization of a Democratic-Republican party in Connecticut, threatened the Federalists' power in the state. So in 1801 the Federalist-controlled legislature passed a law to intimidate Democratic-Republican voters. It was known as the Stand Up Law, which was exactly what it sounds like. Voters literally had to stand up and be counted when the names of the candidates they wanted to vote for were called. Anyone who was brave enough to stand up for a Democratic-Republican candidate would be publicly known to their neighbors, and the ever-present clergy, as a disorganizer, and faced being shunned by their community.

Prior to the 1800 election, the Federalists had warned that if Jefferson won, religion would be destroyed. Once he was elected, that didn't happen, but Federalists never stopped making that argument. How did they keep it alive?

They were always on the lookout for new "evidence" that there was a plot to destroy religion. The Federalists were very fond of plots. Sometimes an event would happen that they would spin as proof of this plot against religion.

For example, in 1804, when Jefferson was running for re-election, a meeting house in Lebanon, Connecticut, was torn down by a mob. There it was — proof that their prediction of churches being torn down if Jefferson were president had been true. As it turned out, the tearing down of this meeting house had nothing to do with Jefferson's Democrats. It was a dispute among the members of the church's congregation over whether or not their rundown old meeting house should be repaired or torn down and replaced, and one faction of the congregation went ahead and tore it down. But the facts of the story didn't stand in the way of the Federalists using it as evidence of the plot against religion.

They'd also discover new evidence of Jefferson's irreligious nature from time to time, such as reports of his traveling on the Sabbath. Anything, or sometimes nothing, was enough to revive their cry that religion was in danger.

Like Republicans today, Federalists repeatedly relied on fake news, unverified rumors and conspiracy theories, many tied to France. One early example you discuss was the rumored rebellion in Kentucky in 1803. What was that about?

That rumor was started in the Federalist papers in New York, one of them the paper founded by Alexander Hamilton in the wake of Jefferson's election, and spread throughout the country. The basic story was that Kentucky had raised a militia force of 15,000 — or 20,000, depending on which paper you were reading — and was in rebellion against the government of the United States and preparing to march on New Orleans. The reason for this alleged rebellion was that France had taken access to the port of New Orleans away from the Americans, and the federal government hadn't done anything about it.

What political purposes did that serve?

The Federalists had wanted to go to war with France for years, and ate this story up because they saw it as a reason for war with France. Although Spain had ceded Louisiana back to France in 1801, France was slow to take control of the territory, and it was actually Spain that had revoked America's rights, but the Federalists didn't know this. There were also Federalists who wanted New England to separate from the Democratic western and southern states, so they liked this story for that reason. Kentucky being in rebellion against the United States was a fine reason for a civil war.

How was that resolved?

The restoration of America's access to New Orleans was obtained diplomatically by the Jefferson administration, and not long after this the Louisiana Purchase took place, which was the last thing the Federalists wanted.

In 1804, the Democratic-Republicans focused attention on the need for a state constitution in Connecticut, which became the principal issue in that year's election. How did the Federalists respond and what was the result?

The Democratic-Republicans had been calling for a constitution since 1801, when they held the first of what would be a number of large annual festivals. In 1804, they called a convention with delegates from 97 towns to prepare for a constitutional convention. The convention issued an address to the people of Connecticut detailing all the reasons that the state needed a constitution. There were quite a few reasons, but the biggest ones were the separation of powers, expanding suffrage, and of course religious freedom.

In response, Federalist council member David Daggett anonymously published and widely distributed a pamphlet titled "Count the Cost." Daggett started off this pamphlet by lying, saying he didn't hold any office and was just an interested citizen. Daggett argued that the charter of Charles II was a constitution, and that to say Connecticut had no constitution was "a gross absurdity."

Much of the fear-mongering pamphlet was spent equating the Democrats to the revolutionaries in France, claiming that the call for a constitution was "entirely in a spirit of Jacobinism," that the goal of the Democrats was to abolish all religion, and that they would follow the course of France, which also started with holding a convention. As ridiculous as his arguments were, Daggett's pamphlet worked, and the Democrats did worse than usual in the election that took place shortly after the pamphlet came out.

In 1805, Democratic-Republican state manager Alexander Wolcott sent a circular letter to the party's county managers about voter mobilization — essentially what we would now describe as voter registration and "get out the vote." How did the Federalists respond, and what does this tell us about them?

Here we have yet another parallel to today's Republicans. The Federalists accused the Democratic-Republicans of trying to rig the election. They were afraid that more men voting might put them out of power. That's also why they opposed expanded suffrage. They wanted to keep voting restricted to those who met property qualifications — their people, not the riffraff who would vote them out of power.

In 1806, you note the impact of an Federalist pamphlet titled "The Sixth of August," which compared the Democratic-Republicans to the French Jacobins. In the same year, you note that a theme emerged in Democratic-Republican papers questioning what principles the Federalists actually stood for, "other than religion and being against anything Republican." How were the state's politics changing?

The "Sixth of August" pamphlet was named for the festival the Democratic-Republicans held that year in the heavily Federalist town of Litchfield. They picked that town because the editor of a Democratic-Republican paper was in jail there at the time for libel against a Federalist county magistrate after printing that this magistrate had attempted to intimidate a voter at the last election. This pamphlet equated the Democrats to the French by listing all the festivals the Democrats had held — because you know who else had festivals? The French!

And yes, the Democrats started to question exactly what the political principles were. While the Democrats had a clear stated platform, the Federalists agenda was just to stay in power by attacking the Democrats and making people afraid of them. And there's yet another parallel to today's Republicans: The Republican National Convention this year put out no platform, and their entire strategy seems to consist of attacking the Democrats and making people afraid of them. Like today's Republicans, the Federalists constantly told the people how great and prosperous things had been under their rule, and of course boasted of how religious they were and claimed that the Democrats were against religion. Watching the RNC was really like watching history repeat itself.

In 1811, Episcopalians in Connecticut voted Democratic-Republican for the first time. Why was that so significant and how did it come about?

The Episcopalians, although technically religious dissenters, had always largely voted Federalist. They were considered more respectable than the other dissenters, and were treated somewhat better by the Federalists than the Baptists and Methodists were. But the Federalists wouldn't give them everything they wanted: In particular, the Federalist legislature wouldn't let them incorporate a college despite repeated requests. As far as the Federalists were concerned, the Congregationalist Yale College was going to be the only college in the state. In spite of this, Episcopalians continued to vote Federalist. But in 1811, the Democratic-Republicans chose an Episcopalian as their candidate for lieutenant governor. So, for this one year, the Episcopalians voted with them. If it hadn't been for the War of 1812, this change might have continued, but in 1812 the Episcopalians went back to voting Federalist. But the 1811 election did show the Democrats that with the right candidates they could bring this significant minority over to their side.

The War of 1812 overshadowed everything else in Connecticut for the next several years, with the Federalists so strongly opposed to the war that they threatened secession. How did they justify that?

As weird as it might seem, only 30 years after the Revolutionary War, the Federalists had become very pro-British. They opposed the War of 1812, and declared it unconstitutional. Some even wanted New England to secede from the United States and form a separate peace with England.

So what did they do?

The Federalist clergy played a big role at this time. What needs to be understood here is the reach the New England Federalist clergy had. They didn't just preach sermons to their congregations that went no further than that. There were some who were nationally known, like a Pat Robertson or other televangelist might be today. Their sermons were published and widely read.

They had always preached against the Democrats and spread lies and conspiracy theories, but they totally outdid themselves with their pro-British sermons during the War of 1812. Words like "treason" and "sedition" were often seen in the Democratic papers to describe these sermons. In fact, there was one that was so pro-British that it was reprinted in Canada and recommended to ministers there to imitate as an "unparalleled" example of British patriotism.

But the biggest and most outrageous thing the Federalists did was to hold the infamous Hartford Convention. In 1814, the legislature of Massachusetts called for the New England states to hold a convention in Hartford that December to confer about their grievances and discuss measures to possibly call a convention of all the states to amend the U.S. Constitution. The legislatures of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island officially sent delegates to this convention, and while the legislatures of Vermont and New Hampshire didn't officially send delegates, a few Federalist towns in those states sent their own delegates.

The convention was considered an act of treason and rebellion by the Democrats, and with a good number of the delegates being known to want a separation of the states, there was speculation that the convention could spark a civil war. The convention rose in January 1815. It did not call for a separation of the states, but resolved to propose a number of constitutional amendments, and that if the federal government didn't concede to their demands, they would reconvene in June in Boston to discuss further measures. Commissioners were sent to Washington from Connecticut and Massachusetts, but by the time they got there the news that the Treaty of Ghent had been negotiated had reached America, and the war was over. So that was that.

What were the consequences of this flirtation with secession?

The stain of the Hartford Convention on the Federalist party, not just in New England but throughout the country, was really the end for the Federalists, although they hung on for a bit longer in New England. The last time they ran a candidate for president was in 1816 and they lost by a landslide, with Federalist Rufus King getting only 34 electoral votes to James Monroe's 183.

After the war, the dynamic that had begun in 1811 — with Episcopalians shifting their support to the Democratic-Republicans — returned full force, electing a non-Congregationalist to statewide office in Connecticut for the first time. What went into this victory?

A few things happened in 1815 and 1816 that turned the Episcopalians away from the Federalists. The first was the Phoenix bank. In 1814, a group made up largely of Episcopalian backers petitioned the legislature to charter a new bank in Hartford, and as was the practice at the time, the bank's backers would pay for the privilege of being granted a charter. For the Phoenix Bank the amount of this "bonus," as it was called, was $50,000. This money would then be appropriated by the legislature, and it was understood by the Episcopalians that $20,000 of it would be appropriated to their Bishop's Fund. But in 1815, the legislature voted against this, although giving Yale College's medical school got its share.

In 1816, Connecticut's Democratic-Republicans rebranded themselves as the Toleration Party. The Democrats met with the Episcopalians, and out of that meeting came a highly unusual ticket for governor and lieutenant governor, consisting of an ex-Federalist for governor, and an Episcopalian Federalist who was a friend to religious freedom for lieutenant governor. Their lieutenant governor candidate won, becoming the first non-Congregationalist to be elected to one of the state's two highest offices.

Also in 1816, the legislature passed what was known as the Appropriation Act. At the end of the War of 1812, the federal government owed the state governments money for their military expenditures during the war. Connecticut claimed it was owed $145,000, and appropriated it to be divided among all the religious denominations. This was seen by the dissenting denominations, including the Episcopalians, as nothing more than an attempt by the Federalists to buy their votes, and just strengthened support for the Toleration Party, which now consisted of the Democratic-Republicans, religious dissenters of all stripes, and many disaffected Federalists.

In 1817, the Democratic-Republicans' candidates for both governor and lieutenant governor won, and the Democrats also won a majority in the House of Representatives for the first time. It was at this point that Thomas Jefferson wrote to John Adams, "I join you therefore in sincere congratulations that this den of the priesthood is at length broken up, and that a protestant popedom is no longer to disgrace the American history and character."

So how did this finally bring about religious freedom and equality?

The Democrats still had to get control of the state's governing council, which they did in the next election. In 1818, with the entire government in Democratic-Republican hands, the legislature proposed a constitutional convention, which convened in August. In October the people of Connecticut voted on their constitution, and although the vote was close, it was ratified, and the state finally had religious liberty.

What lessons for our own time can we learn from this prolonged and almost entirely forgotten struggle?

Well, you can see from the newspapers of the time how divided the people were, and how vicious the attacks were, and there are just so many parallels to what's happening right now. The party in power would do anything to hold on to that power, using fear-mongering, conspiracy theories, outright lies and, of course, religion to hang onto their base. But eventually part of that base defected — the Episcopalians and the disaffected Federalists had had enough.

I think we're seeing something like that now, with so many Republicans coming out against Trump. I don't know if there's really a lesson to be taken from it, but it is a hopeful story, and I think the book — especially all the great poetry and satire in it — will provide a pleasant diversion while waiting to see what happens in November.

Shares