On Monday, a group of scientists published a paper in the journal Nature Astronomy revealing the presence of phosphine in Venus' upper atmosphere. The researchers spent three years attempting to find a plausible explanation for the existence of the phosphine besides the presence of anaerobic organisms, and could find none.

"If no known chemical process can explain PH3 [phosphine] within the upper atmosphere of Venus, then it must be produced by a process not previously considered plausible for Venusian conditions," the authors write. "This could be unknown photochemistry or geochemistry, or possibly life."

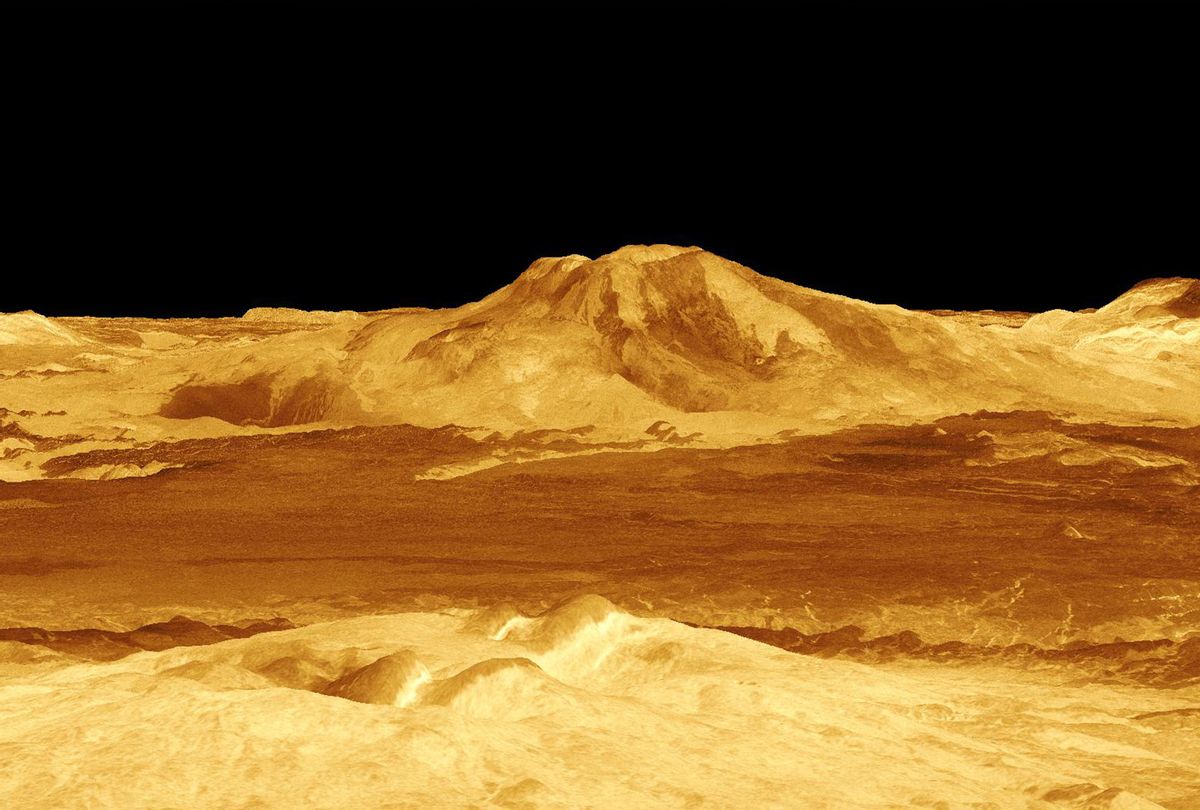

With that article, the world has changed — possibly forever — for scholars who specialize in studying the second planet from the Sun.

"Personally I find it exciting," Noam Izenberg — a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and deputy chair of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (VEXAG), which was established by NASA in 2005 — wrote to Salon. "The Venus science community is about as energized as I've seen it in well over a decade. Whether or not this specific finding is verified or falsified by follow up investigations, it drives us to learn and know more. It highlights how much we don't know about Venus, and that fundamental new discoveries, possibly relevant to and reflective of the history of our own planet, await us next door."

Izenburg said that his colleagues in VEXAG had been advocating for a Venus exploration program akin to the one currently in place for Earth's other celestial neighbor, Mars. Izenburg told Salon that each new finding about Venus "shows us that Venus holds uncounted discoveries relevant to planetary science — including Earth, and including the almost daily growing catalog of exoplanets. If findings like this help push the needle to get people like [NASA] administrator [Jim] Bridenstine to tweet 'It's time to prioritize Venus.' I am definitely encouraged."

Salon also reached out to David L. Clements, who studies physics at the Blackett Lab of Imperial College London and was one of the paper's co-authors.

"It is clear that finding phosphine in the upper cloud decks of Venus is a problem in the sense that normal chemical processes shouldn't make anywhere near as much as we see," Clements wrote to Salon when explaining the significance of the team's findings. "That requires an explanation that goes outside what we think we know about the atmospheric chemistry or biology of Venus." He added that he and other researchers had analyzed the various alternative explanations for why there might be phosphine in Venus' atmosphere and they all "came up short."

In terms of what scientists can do next to confirm or refute the possible presence of life on Venus, Clements told Salon that "the trick is to come up with something that is produced by life that isn't produced by anything else. So, for example, if these putative anaerobic bacteria in Venus produced carbon dioxide as a waste product, we wouldn't be able to tell because the atmosphere of Venus is full of carbon dioxide anyway."

He added, "That is what makes phosphine so useful — it shouldn't be in Venus' atmosphere so finding it is a sign that something we don't understand — maybe life, or maybe unexpected chemistry — is going on. Until we have a better idea how life in these clouds might work it is difficult to come up with any clear predictions."

Ingo Mueller-Wodarg, who also teaches at the Imperial College London and is a co-author of the paper, echoed Clements' observation about the significance of the presence of phosphine.

"We have looked into this quite carefully and cannot currently any alternative interpretation for the phosphine in the atmosphere," Mueller-Wodarg told Salon by email. "This doesn't mean a proof for life, but an absence for alternative explanations."

Mueller-Wodarg argued that "more work needs to go into identifying minor constituents on Venus" as well as "better understanding the chemical pathways." He added, "Much previous work has gone into studying the chemistry of Venus' upper atmosphere, hence the surprise discovery of phosphine which hadn't been expected. So, there exists reasonable knowledge already about Venus, though the intriguing question raised by our new observations is whether anything was missed."

Robert Grimm, program director at the Southwest Regional Institute in Boulder and former VEXAG chair, wrote to Salon that he anticipates an increase in American studies of Venus as a result of the new discovery.

"US-led Venus research and exploration has been lagged behind other worlds since the completion of the Magellan mission in the 1990s," Grimm wrote to Salon. "Venus is the cornerstone of comparative planetology and is key to understanding where Earth-sized means Earth-like elsewhere in the Universe. It has always been important, but this discovery adds new impetus. Detection of extraterrestrial life could be the most important scientific discovery in history, and the possibility that life exists on our nearest neighbor is eye-opening."

Grimm did urge caution when it comes to believing that this could mean there is definitely extraterrestrial life.

"A flagship publication and extensive press coverage does not mean it is right," Grimm explained. "This paper did a great job of demonstrating their results and laying out (and rejecting) many alternatives, but personally I think it will turn out to be abiotic [non-living]. In the meantime, lots of people are motivated to leave no stone unturned. This is how science should work."

Mueller-Wodarg, by contrast, was extremely excited.

"Of course this is very exciting," he explained. "Venus as a planet is highly complex and fascinating. As Earth's twin it shares a common history and yet turned out so differently. Yet, the prevailing interest in the public often lies with Mars since it reminds us of Earth with its landscapes and many other similarities. Venus deserves a promotion!"

He added, "The broader implication of the discovery is also for us to consider other 'hostile' planets as potential hosts for life forms. This is hugely exciting, it opens up new areas of planetary science and astrobiology."

Shares