In a discovery that could transform our understanding of astronomy, an international team of astronomers reported on Wednesday that they believe an intact exoplanet is tightly orbiting a white dwarf, something previously thought to be impossible.

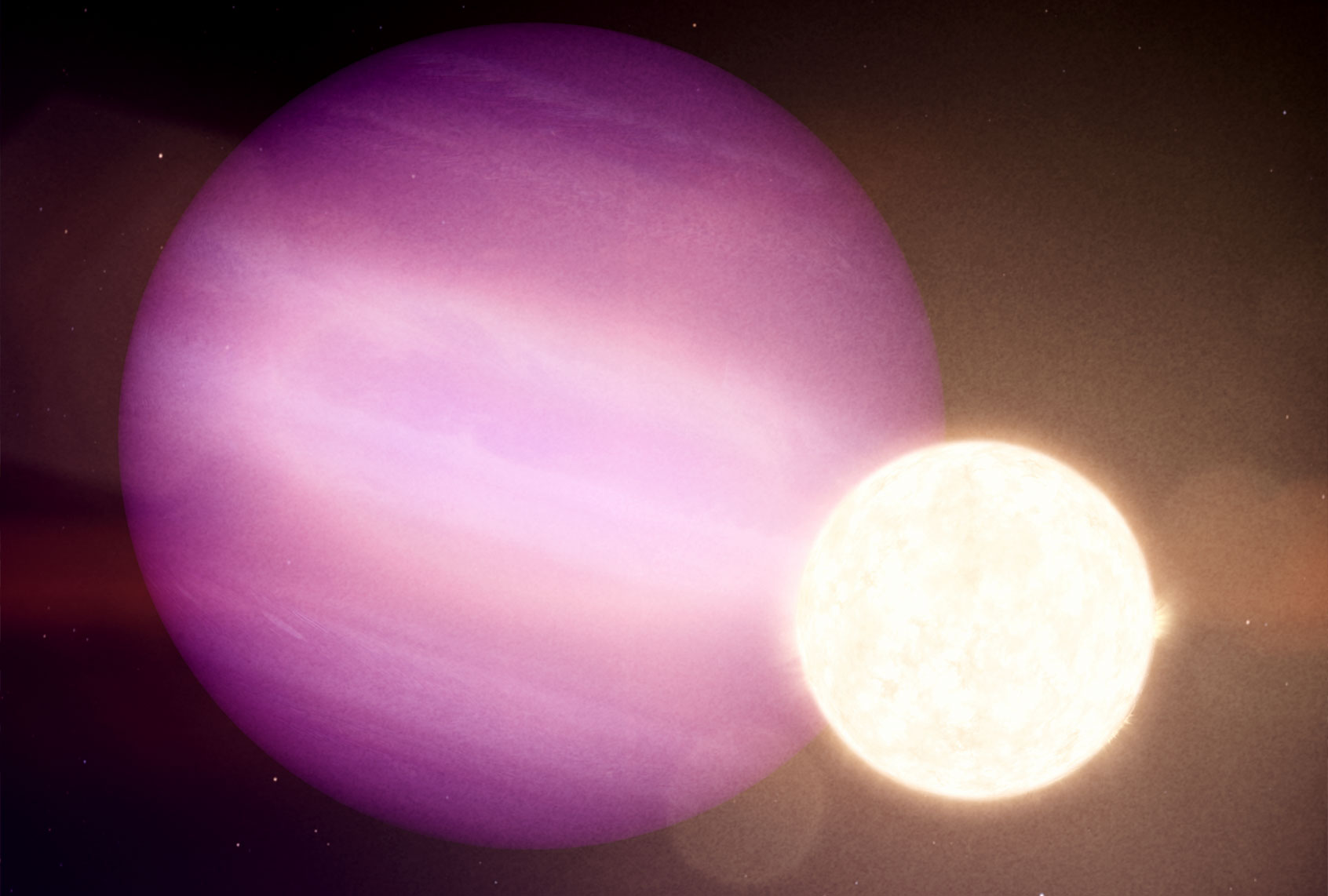

“We report the observation of a giant planet candidate transiting the white dwarf WD 1856+534 every 1.4 days,” the authors write in an article published for the scientific journal Nature. “Transiting” refers to when a planet eclipses the star that it orbits from the perspective of us on Earth, and is a common means by which astronomers search for exoplanets. The paper also explains that the planet candidate is about the same size as Jupiter.

Part of the reason that the discovery is so strange is that it defies so much of what we know about planet formation, as researchers involved in the study explained to Salon. Andrew Vanderburg, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who contributed to the paper, explained the finding’s potential significance.

Stars like our sun “burn” hydrogen fuel into helium in nuclear fusion reactions, which warms up ours and other planets. When stars run out of hydrogen, however, “a couple of unusual processes will occur,” Vanderburg explains. “First the star will swell up and get really, really big. This is kind of like its death throes. Once it runs out of hydrogen, it starts burning helium and turning that into a carbon and oxygen, eventually. But this is an inefficient process and it doesn’t last very long. So pretty quickly after the star runs out of hydrogen, it loses much of its mass, so the outer layers of the star all get blown away into space, and what’s left is the hot core of the star, which is no longer producing energy.”

That hot core, Vanderburg explained, is what we call a white dwarf — and one of the defining characteristics of a white dwarf is that, because of its strong force of gravity, it tends to pull celestial bodies toward it and break them up in the process. The possible planet discovered by the scientists using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite and the retired Spitzer Space Telescope, however, has seemingly remained intact. If this is further verified, it will be unprecedented.

“The explanation that we think is the most likely is that there were other planets in the system or other objects in the system,” Vanderburg explained. “We know that there are two other stars orbiting this white dwarf very far away. Maybe they could have exerted some influence on this planet that we saw back when it was orbiting far away originally because it had to be orbiting far away, or it would have been engulfed. It could have changed its orbit so that it was very, very elliptical, and then when it came in close to the star, it just barely grazed the surface.”

He added, “The other alternative explanation is that the planet actually would have been engulfed by the star, but it had enough heft to essentially save itself.”

Vanderburg also said that, like the recent discovery of phosphine gas in the atmosphere of Venus, the new discovery about this planet could suggest new types of planets to search for life.

“I think the biggest implication for this is that there’s a possibility for life to be in places that we hadn’t really considered before,” Vanderburg told Salon. “Not that people didn’t consider that life could be around white dwarfs — people speculated about that for awhile — but the biggest question that we had was, ‘Can planets actually get to the place in systems where they would need to be in order for life to be similar to the way it is on Earth, but around [a] white dwarf?'”

As Vanderburg pointed out, planets are believed to only be capable of supporting life if they exist in a “habitable zone” — that is, close enough to a given star to benefit from its heat but not so close that the heat eliminates the conditions necessary to support life.

“In a white dwarf system there’s also a habitable zone, but because the white dwarf is really tiny and it’s cooling off and is really, really faint, you have to huddle a lot closer to that star in order for it to be potentially habitable,” Vanderburg told Salon. If the astronomers’ recent discovery pans out, it “is essentially telling us how they can do that.”