Do you like sweet things? A little bit? A lot? While we like to indulge in our sweet tooth here and there, there is of course a downside the habit: excess added sugar consumption is the leading cause of tooth decay, diabetes, and heart problems. If only we could replace added sugar with something else, our problems will be solved, right?

Sugar replacements exist, and we have had them for more than a hundred years (saccharin, for instance, was discovered in 1879, and aspartame in 1965). The problem is that actually obtaining sugar replacements is frequently neither easy nor cheap. However, a group of scientists at MIT has found an efficient way to access an alternative sweetener that may be more beneficial to our health — a win-win.

Added sugars refer to any sugar or caloric artificial sweetener that is added to foods or drinks during manufacturing or preparation. They include natural sugars such as table sugar (sucrose) and artificial sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners include two types: high-intensity and nutritive sweeteners. High-intensity sweeteners are many, many times sweeter than sucrose and so only a little bit is usually enough to sweeten food. On the flip side, nutritive sweeteners are sugar's "cousins" and are slightly less sweet than table sugar. They are derived from sugars through a process known as hydrogenation and can't be degraded by oral bacteria, lessening tooth decay problems. However, diets using artificial sweeteners still correlate with health issues such as an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes.

Other alternative sweeteners known as rare sugars have interesting properties. They are found, well, rarely in nature and have few sources. Rare sugars have shown to help control glucose levels. Studies have shown that D-allose, one of these rare sugars, could be an ideal sugar replacement. D-allose is 80 percent as sweet as sucrose, low calorie, and has potential health benefits. It has anti-oxidant properties and can also induce anti-cancer activity in cells. Yet, more research on safety and metabolism in humans is needed.

One of the things hindering research advancement on D-allose is that it is expensive to obtain due to its rarity in nature. Although slender speedwell, golden bartonia, potato leaves, the Transvaal mountain sugarbush native to South Africa, and chenille plant leaves are known sources of D-allose, the extraction from the latter has shown to be impractical with yields of less than 5 percent. But laboratory preparations are also available. They use D-glucose as a cheap and widely available primary source to produce D-allose. However, these processes are problematic: they have many steps and generate a poor overall yield, about 2.5 percent. Right now, D-allose costs $80 for one-tenth of one tablespoon (about 0.1 grams). So, before it can be used as an alternative sweetener, researchers must look for economical shortcuts to produce it.

A team at MIT lead by Alison Wendlandt recently showed in the journal Nature how to make D-allose from D-glucose in only one step with a little more than 40 percent in yield — about 16 times improvement from the current process.

The recipe is simple: grab a flask, add glucose, a few additives, shake it really well, and voila. It's not that different from making bread dough: combine all ingredients, mix, and wait. However, many years of research are often spent to find an ideal recipe in complex syntheses like this.

Conventional synthetic organic chemistry commonly involves several steps where different parts of a target molecule are built bit-by-bit, like a LEGO structure. But, along the way, some parts of a molecule-in-progress must be "protected" (made unreactive) to direct reactions to a specific region of the molecule. This process "slowly" builds the end target. But chemists like the MIT team are building reactions that do not require these "additional" steps and are often inspired by biological reactions facilitated by naturally occurring enzymes.

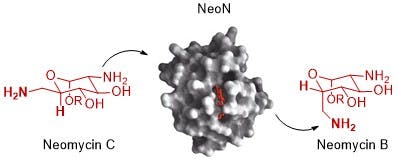

In particular, the MIT team found inspiration in the enzyme NeoN, from the bacteria Streptomyces fradiae. They looked at the biological action of NeoN and realized that this enzyme performs a molecular modification that could be repurposed for making D-allose.

Enzymes are long amino-acid chains folded into hollow ball-like structures. Inside these hollow spaces, an infinite number of chemical reactions can happen. Broadly speaking, depending on the specific molecular makeup of these cavities, enzymes will facilitate different types of modifications. Four years ago, researchers deciphered NeoN's mechanism. In that study, researchers at the Tokyo Institute of Technology found that NeoN modified neomycin C — a less active version of a common antibiotic — by breaking one bond and restoring it, producing neomycin B, the more active and commonly used version, often just known as "neomycin."

Josseline Ramos-Figueroa

This type of modification — known as radical epimerization — is a sought-after reaction for many chemists and NeoN is among a family of enzymes known to have this ability.

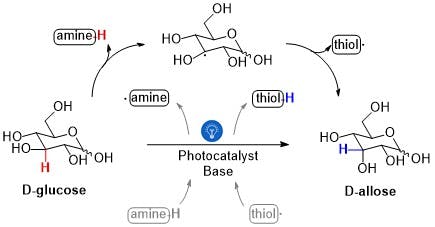

In a similar fashion, the MIT scientists thought glucose could be modified into D-allose. So, after digging into available chemical transformations — reactions made in a flask — that resembled that of NeoN, all that was left to do was trying the different conditions and ingredients found in these recipes to finally end up replicating such incredible enzyme ability.

This was no easy task. The glucose-to-allose transformation required an unstable radical (which would remove a hydrogen from glucose) and a molecule known as thiol (which would return a hydrogen atom, producing D-allose.) But for the reaction to work in the absence of the enzyme's pocket environment, a light-sensitive molecule — a photocatalyst — was required. The photocatalyst not only accelerated the reaction in the presence of light but also was essential to ensure chemical recycling (restoration of the fleeting radical and thiol molecules).

Josseline Ramos-Figueroa

Despite the fact that this modification is extremely specific — to the point that only one side of a tiny glucose molecule is affected — how the whole set of molecules is able to shuffle atoms in a coordinated manner remains elusive for these scientists and others in the field. For a set of molecules to make a reaction happen, they must interact with each other by holding relatively close and specific positions while also receiving or pushing atoms away, sometimes in unexpected, and to date, difficult-to-understand ways.

Although the MIT scientists tested their procedure to make D-allose using only one gram of initial material, a much larger scale is yet to be evaluated to see if the method would hold up on an industrial scale. What's more, the optimized recipe works for more than just glucose. To test the applicability of the technique on other molecules, the scientists mixed in other glucose-like compounds and sugar complexes — known as glycans — such as table sugar. The conversion was observed for at least 15 other molecules and with reaction yields close to as observed for glucose.![]()

As presented, this new development to produce D-allose has the potential to make this rare sugar readily and cheaply available for further exploration in other research areas. In particular, finding answers regarding D-allose's safety for use in human diets would quickly make this rare sugar, perhaps, more appealing as an alternative sweetener. But not only that, the use of D-allose is of increasing interest as a treatment to reduce disease development in rice crops, enhance the treatment for parasitic infections in animals, and treatments such as immunosuppressant, anti-osteoporosis treatment, and cryoprotectant that have been proposed but are yet to be tested in humans.

Shares