"The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel," is Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott's essential follow-up to their 2003 documentary, "The Corporation." That film, as this new one recaps, showed how large public corporations have become the dominant institutions of our time, and have even been deemed by law to have the same rights as a human being.

In the original documentary, the filmmakers — Mark Achbar and Abbott directed; Bakan was a writer — provided a psychological profile of corporations. They demonstrated that businesses were pathologically self-interested. This new film, which had its World Premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, looks at how corporations have changed, in that they are now promoting greater social responsibility, but also how they have not — they create greater inequality, threaten the environment, and unduly influence the government.

The emphasis here is twofold. First, the filmmakers present 10 rules out of the New Corporation's playbooks, from using information to control people and exploiting an unequal advantage to breaking laws that get in their way. They feature observations and commentary from Robert Reich, Sandra Navidi, Wendy Brown, and Anand Giridharadas, among others, that provide context for how corporations are contributing to the breakdown of society. The second part of the film addresses democracy both in crisis and in action, with social movements like Occupy and Black Lives Matter working to create real change.

The filmmakers spoke with Salon about the bad behavior of corporations and their forceful new documentary, which is sure to provoke righteous outrage. Bakan also authored the companion book, "The New Corporation: How 'Good' Corporations Are Bad for Democracy," out Sept. 22.

Your new film shows that while corporations have done better in being more socially responsible, that this is, in fact, a myth. For all the money JPMorgan Chase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon "invests" in Detroit, his company received a bailout from the 2008 financial crisis that obliterated the communities that he is "helping" now. Can you discuss this idea of corporate America reinventing themselves as saviors?

Joel Bakan: If you go back to when the first film came out, there were globalization protests and the wheels turned to the point that corporations became so large and multinational that they challenged the capacity of governments to regulate them. So, it was a tipping point where corporations shifted from being powerful actors to dominant actors. That's what we captured in our first film. In 2004-2005, corporations got the message, and they got the sense that people were very concerned about their growing power, impunity, and negative footprint on the world, so they worried that the legitimacy of their growing power was in question. Their response was to come out with a public relations rebranding and say, "We may have been psychopaths and self-interested before, but we are better now. We are reformed now. We got the message and we are going to be a solution to the problem." That was the remake, but despite the remake and the actions they took, the institution of the corporation remained the same, and nothing changed in the imperative to chase profit.

There is also a case study presented in the film of the for-profit Bridge International Academies, which people like Bill Gates fund with $5 million that basically profit from the poor. You take corporations to task in the film for this insidious kind of privatization. Can you talk about this process, and what you discovered?

Jennifer Abbott: Part of the neoliberal agenda has been to promote privatization and this notion that government is the problem and inefficient, and that the private sector can do better in organizing things like the post office. The example of Bridge is a particularly creepy example partly because the people doing the privatizing seem to be so nice about it. But there is another dimension that Bridge is colonization, pure and simple. Silicon Valley corporations are going into Africa, exploiting the poor, and sucking out public funds from the government by creating for-profit schools that are detrimental to the children. They don't have qualified teachers, which is how they make them profitable. They give teachers tablets that [instruct] them to, "walk two steps to blackboard, talk to the student one-on-one, etc."

Bakan: Corporations are going into Africa because other systems are not working. So, it seems like a good thing, but the public systems don't work because we have these companies providing education, so we don't need to fund it much. A little privatization begets more privatization, which gives governments leeway to cut back on social services.

Corporations control the wealth because they have tax havens and benefit from tax cuts. This has the — to use the Reaganomics term — trickle-down effect of giving the government less money, which causes social problems to grow. There are also environmental and health concerns that stem from this behavior. Can we shift power away from corporations or hold them more accountable?

Bakan: Of course we can. The corporation is a creation of the state and government. Corporations were created in the 19th century by legislative and judicial systems. They make profits that both the government and the state say shareholders are not liable for harms caused by the business. Corporations can disappear by stroke of a pen. How can we generate political will to contain, not end, corporations? It is an easy thing for the government to do — pass laws or reform laws. It's really about political will. We spend the last third of the film asking how we instill a sense in citizens to have the power to do this. The corporation feels immovable, but it is purely a social and political construct. Our task is to make that point and then say to people what we really need to do this is to empower ourselves as democratic citizens and take control of this thing to live in a sustainable and just world. There is no technical impediment to that. It's a matter of will.

Another point your film makes is how corporations work to make data profitable. We've seen how technology has been exposed to show racial bias, but as someone in the film warns, "putting faith in a corporation only takes us further down the path that led us here." How can we prevent society becoming a market and stop a behemoth like Amazon?

Abbott: The crucial thing is outside power, so Amazon has outside power and undue influence and that's a big problem. But the corporation is a construct of the state, so it is the responsibility of the state to rein in the outside power. It has to have the political will to do that. It has to cut its link to big corporations so it doesn't feel it has to act on their behalf. It's more complicated now because in the U.S. it is tough to differentiate who is working for the corporation and the government. We include a story about Ada Colau, an anti-eviction housing activist who was elected the first woman mayor of Barcelona. When she got into power, she had no one in her phone who has economic power in the city. The other thing that is essential to understanding big technology isn't about privacy. But it's more about control. What do they do with the data they collect is that they predict how we are going to live the rest of our lives. They customize products and services that control our behavior. We do not have full agency in that instance through our seduction of small comforts and conveniences we get from technology.

There are also issues of corporate regulation that have failed to protect people — the Deepwater Horizon disaster, for example. Governments are tilting towards the corporation even as they "charm us to believe they are part of the solution." Can you discuss this insidious practice?

Bakan: The Deepwater Horizon story is really interesting because it undermines the central point in the film. We get Lord John Brown, former head of BP, talking sincerely and convincingly about how much he cares about safety. And we believe he cares about safety. But he's working in an institutional framework where the mandate of his company is about profits. He focuses on personal safety, but he neglects process safety and cuts process safety significantly. That leads to explosions and failed pipelines. Even though he was not at BP when Deepwater Horizon happened, the trajectory of the culture that happened is [his legacy]. There is a false notion that corporations can care in a genuine and important way about environment and [safety]. It's a tragedy.

There was a recent news item about the Boeing 737 crashes and infrastructure that is so relevant. The committee released its report, and the former CEO of Boeing before the crashes thanked Trump for relaxing regulations. It's a clear example of when governments relax regulations, tragedies occur. Given the context of the upcoming election, all of the CEOs and all corporations that say they are good now are lobbying Trump for more deregulation and more tax cuts. They love what Trump is doing from a business perspective. Even while they are saying they believe in racial justice, they leverage Trump to deregulate and privatize. They are talking good talk and even criticizing Trump, but they are lobbying further to dismantle any meaningful controls on corporations.

The ramifications of these practices are inciting greater waves of hate, fail to make our lives better (as promised), and weaken whatever trust we have in the government. The answer, your film advances is to find the capacity to resist, get involved, and demand a new brand of democracy. How viable is this, really?

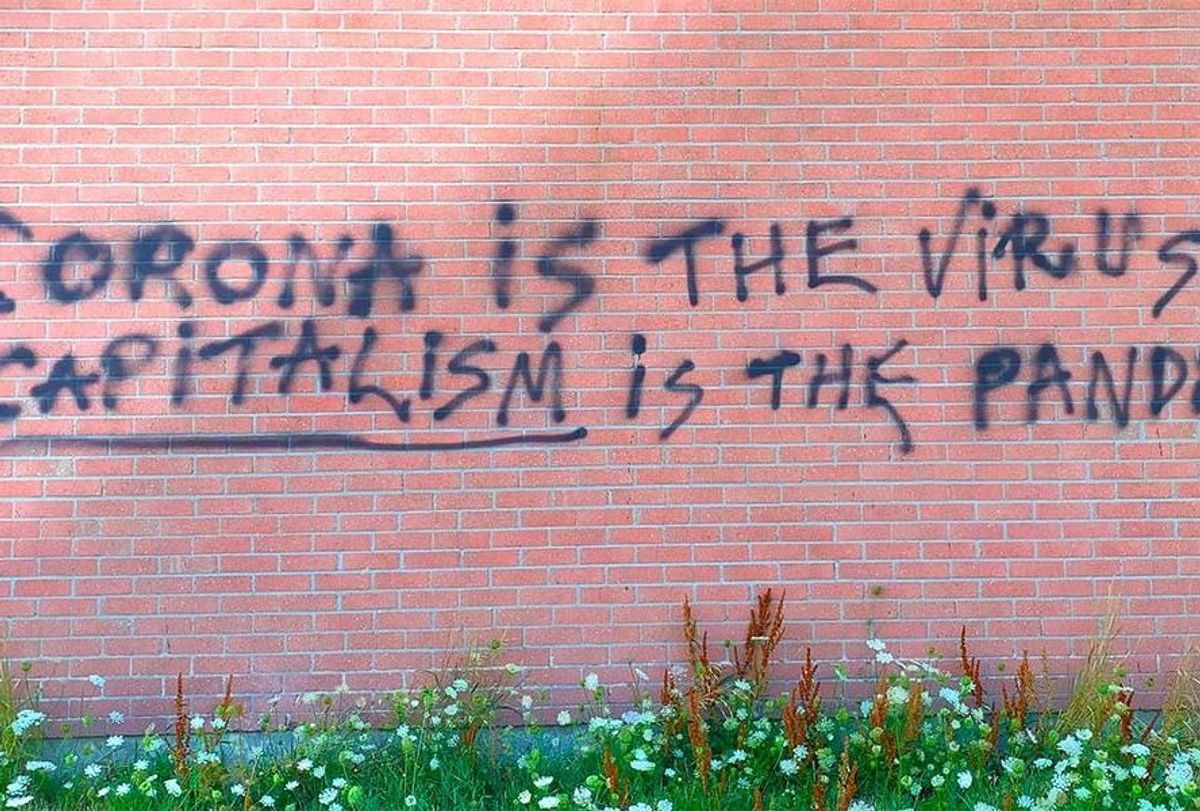

Abbott: We were trying to get away from the idea that we can affect change solely through consumption. Reinvigorating democracy and finding our place within engaged citizenship — that is how we will amass power to challenge the corporate behemoth. We were adamant to include the pandemic and the uprising after George Floyd's brutal murder. Activism is so important to include because its size. Challenge the system and questioning why public funds are allocated to police and military while hospital workers are using garbage bags as protection, or inequality is seen along racial lines. It was essential to include because there was this moment — even Angela Davis says, "I never thought I'd see this in my lifetime." We are trying to change the world. It was an important moment to include because it provided a hopeful ending.

One person who returns from the original film is Chris Barrett. You showcased him 17 years ago as a college student who was looking for corporate sponsorship. Now he has embraced Bernie Sanders and his Democratic Socialist message. Barrett even ran for office in New Jersey and became an elected official. You encourage people to get involved at the grassroots level to effect change and create a different future. Let's end on a hopeful note: What other positive changes have you seen since the last film?

Bakan: We try to show a few examples of a particular model of activism that seems to be gaining momentum, and that is for people to run for office and stay connected to social movements and for social movements on the left to do what the right did with the Tea Party — work at local, state, and national levels. Bernie said, "Go run for office," and 7,000 young people joined this movement and ran for school boards and city council. We see a wave of young progressives in congress following Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. We see cities electing progressive mayors and city councils. We didn't need to look far to find inspiring examples; what we needed to do was figure out what stories to tell because there are so many happening in small towns like Chris Barrett, or Chokwe Antar Lumumba in Jackson, Mississippi. It's happening around the word. One trajectory moving forward is one that Mike White, one of the initiators of Occupy, says in the film is that social movements and large-D Democratic politics are coming together in a powerful way. I don't think it's a coincidence or anomaly that Bernie got the support he did twice. That an open Socialist twice was successful and a contender to be President of the United States — something is happening in the political arena and not just the marketplace. It's in towns, school boards, and city councils. It's a positive trajectory, and it won't go away regardless of the election. Re-enlivening of local politics is a reaction to the Trump administration. People think it's not working, but we can make headway in our cities, and communities, and municipalities. That's what give me hope.

Shares