As the longest sustained period of racial justice protests in American history segues into the heat of election season, dark shadows have appeared, from the vigilante killing of protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin — and widespread conservative defenses of the teenage accused murderer — to ludicrous charges against protesters, including "terrorism," to the Trump administration's crackdown on federal antiracism training, calling it "anti-American," and Attorney General Bill Barr's call for protesters to be charged with sedition.

So much for the notions that Donald Trump has no ideology, or, for that matter, that getting rid of him will make America great again. In July of 2016, I wrote about why such views were myopic: "Trump advances core paleoconservative positions," researcher Bruce Wilson told me, including "rebuilding infrastructure, protective tariffs, securing borders and stopping immigration, neutralizing designated internal enemies and isolationism."

Trump's record as president has been surprisingly consistent for such an erratic figure, with his purely rhetorical support for infrastructure as the most notable exception. And therein lies a key to the current moment: With infrastructure removed from the equation — the most broadly popular position Trump's ever embraced — the remaining white nationalism stands out in stark relief, highlighted in the frenzied push toward violent confrontation around the election, and beyond.

Dr. James Scaminaci III has just published a report about the long historical genesis of this recent push for Political Research Associates, "Battle With Bullets: Advancing a Vision of Civil War." Scaminaci has a PhD in sociology from Stanford and has worked as a civilian intelligence analyst with expertise on the former Soviet Union, the former Yugoslavia, and organized crime. So the spread of social chaos, internecine violence and associated enabling ideologies is a subject he's familiar with.

Scaminaci traces the roots of culture-war and race-war narratives as far back as the Haitian revolution of the early 19th century. He observes that Steve Bannon nurtured those carefully at Breitbart News and they have played a key role in radicalizing Trump's base over the past five years, to the point where some of his supporters are visibly preparing themselves for violence. Some parts of this story have been relatively well covered, but Scaminaci provides a much more integrated and historically extensive account of how we reached our present state. I reached out to him recently for an interview by email to discuss some of his key insights and how they provide us with a much clearer picture of the forces pushing America toward civil war. The following has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

In your article, you write: "Over the last several years, a narrative around the threat of civil war — and more specifically, a racial civil war — has been growing on the Right." You observe that this comes in different versions and has deep historical roots, dating back to the colonial era. Before getting into the details, why is it important to recognize this history and learn about it?

I wanted to convey that what we are seeing now on the right wing has a long history, a history that is either overlooked or ignored. Jill Lepore and other scholars looking at the right have noted that modern day "patriots" cast themselves as lineal descendants of the founding fathers and the American Revolution — that they are revolutionaries against the existing "tyrannical" federal government. But that history is drenched in violence and blood against Black and indigenous peoples. That context cannot be omitted. And the idea that whites are under existential threat from Black folks also needs to be put into historical context.

Second, the right-wing idea that the federal government is "tyrannical" is largely the product of white supremacist politicians, both Republican and Democratic, and intellectuals like William F. Buckley. This was the idea that post-World War II federal support for civil rights was federal overreach, was unconstitutional, and that it upset allegedly harmonious race relations in the South and eventually in the North.

According to white supremacists, the existential threat to white people in the Jim Crow South came from Black folks, whether children or adults, even touching anything that could be shared with whites. A schoolbook touched by a Black child became a Black textbook. Blacks and whites could not share drinking fountains or sit in the same seats on a bus.

What I wanted to portray in "Battle With Bullets" is that whites have long viewed any expression of nonviolent Black agency as an existential threat to themselves that required whites to resort to a brutal, genocidal racial civil war. One can understand the palpable fear of a slave revolt before 1861. But white supremacists have claimed that registering to vote, voting, moving into a white neighborhood after a history of redlining, moving into managerial or foreman positions in the workplace, or being cast as heroes or superheroes are existential threats.

You write that "The most dangerous versions of that [civil war] narrative come from leaders with paramilitary forces, while other appeals seem intended to generate a heightened sense of crisis." Can you give an example of each and then help us understand how the two are related?

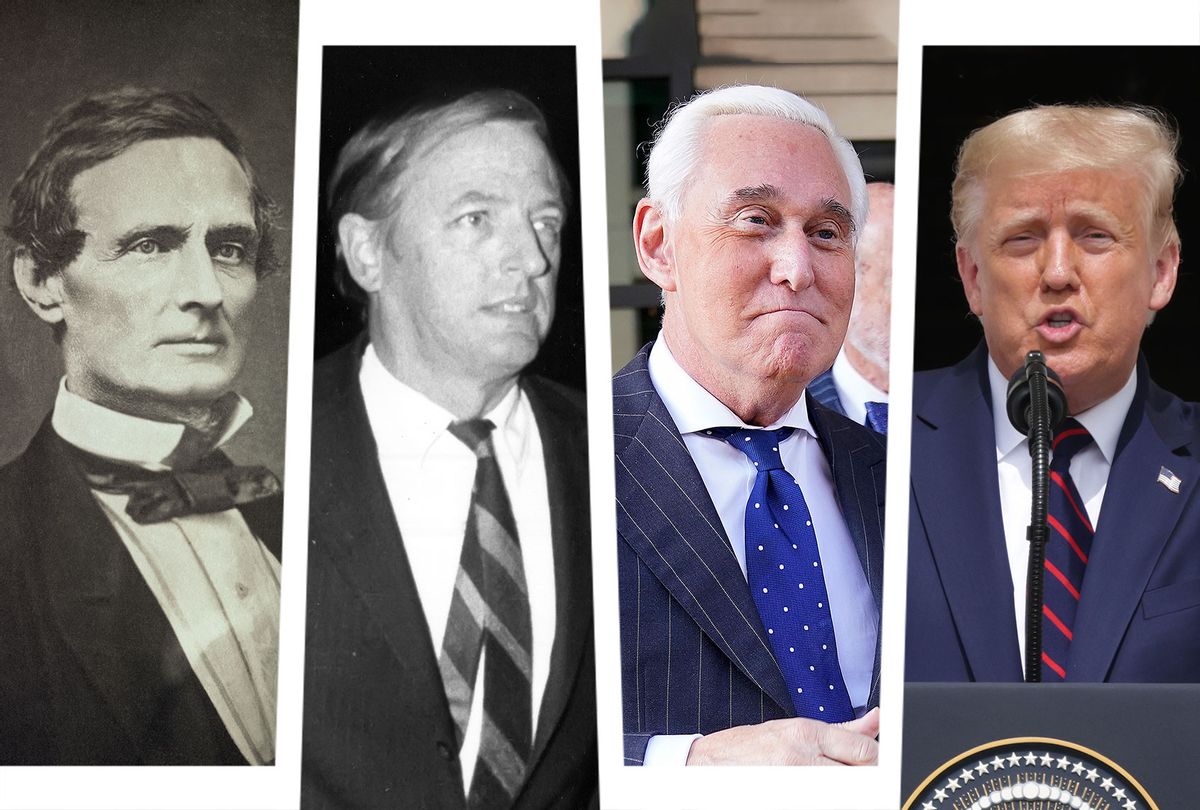

Roger Stone is a political operative who has graduated from ratfucking political operations into calling for a civil war or violence or martial law. He is an ideological chaos agent. He can help set the narrative mood for the right wing. As Chip Berlet has written, elites know how to write the score for scripted violence. Somehow, the gunmen always know who to kill. In a similar category are the numerous Christian right leaders who broadcast the same civil war message to their Christian nationalist supporters and followers. I also quoted [Dallas megachurch pastor] Robert Jeffress in the article.

David Neiwert owns the beat on tracking the transmission of fringe ideas to the conservative mainstream. Even a decade before Trump, the ideological lines were blurring.

In 2008, Michael Savage, a right-wing radio host, said, "[T]he white person is being erased from America's future. ... There is a racial element to the immigration invasion." Then Fox News commentator Bill O'Reilly claimed, "So now, it's becoming a race war." The Center for American Progress went on to note that O'Reilly claimed that immigration reformers "hate America ... because it's run primarily by white, Christian men" and were seeking "to change the complexion...of America."

That is no different from Jean Raspail's theme in "The Camp of the Saints" or the narrative at The Social Contract, a white nationalist journal which published Raspail's novel. Or Glenn Beck on Fox News in February 2009, airing his racial civil war scenario within one month of the first Black president taking office. Or a variety of Christian Right leaders during the Obama years calling for or suggesting a racial civil war is coming, including Tony Perkins, Larry Klayman and Rick Joyner.

In 2006, the Southern Poverty Law Center noted the "symbiotic dance" between white supremacist groups and John Tanton's hardline anti-immigration movement, as well as the sharing of conspiracy narratives between white supremacists and the "patriot" militia movement.

The conservative movement, both the political and religious wings, transmit sanitized versions of white supremacist ideology. The latter is premised on preparing for, if not instigating, a racial civil war in America.

John Jackson, a scholar who covers "scientific" racism, in a recent article titled, "Going Full Nazi,"asked the question: "[W]hat is the point of drawing a line between the 'mainstream' and the 'alt' right? Perhaps there is no useful distinction to be made." The angry white guys with guns are dangerous because they have weapons of war. But the dividing line between them and the "Fourth Generation Warfare" chaos agents creating a crisis of legitimacy is increasingly blurred.

You write that this rhetoric is rooted in a narrative adapted from the 1973 French novel you just mentioned, "The Camp of the Saints." Can you explain its basic narrative?

The novel has seven key ideas that its critics and proponents have noted. One, mass migration is an invasion. Two, immigrants and refugees are invaders. Three, the invaders will eventually destroy Western culture and replace Western populations. Four, the West's political elites do not have the moral strength to defend the West. Five, the invaders must be physically removed and/or violently repelled. Six, there is a difference between the "real country" and "real citizens" and the "legal country" and "legal citizens." Seven, multiracial, multiethnic or multi-confessional societies are not only unstable but undesirable, and lead to the "balkanization" of societies — a view also imported from Serbian genocidal propaganda into the American and global right.

The main variations within this "Camp of the Saints" worldview are whether the political elites lack moral strength to resist the invasions ("Great Replacement"), enact immoral policies which weaken Western societies to invasion ("demographic winter") or actively collaborate with the governments of the invading migrants to facilitate the invasion (as in John Tanton's network). The other variation distinguishes the neo-Nazis from all the other segments: whether or not the Jews are responsible for the destruction of their societies ("white genocide").

You note that for both France and the United States, the historical roots of this narrative go back to the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804. In the U.S. this has produced the "white genocide theory" and in France the "great replacement" theory. What distinguishes them and what draws them together?

The "white genocide" theory is premised on the fear of a Black slave revolt against the white slave-owning society. The "great replacement" theory is based on the fear of massive nonwhite immigration coupled with lower white birth rates leading to a "replacement" of the white population with a nonwhite population, and the transformation of the culture.

White supremacists use the more palatable, more sanitized "great replacement" theory interchangeably and conflate them. But they have different causal mechanisms.

On the other hand, the neo-Nazis and other proponents of the "white genocide" narrative consider any action by Black people to improve themselves, to gain access to privileged white spheres of social action or to more equitably redistribute power and status as an existential threat. "Great replacement" proponents do not share this outlook. Nor do "great replacement" proponents, in general, blame Jews for what they consider to be massive immigration.

You write, "It would be a mistake to see these various 'White Replacement' narratives as isolated from mainstream conservative thought in Europe or America." How has their influence spread through terrorist acts?

In the right-wing information sphere, ideas swirl around, mix, recombine and mutate over time to fit changing circumstances. Raspail's "Camp of the Saints" is foundational to this narrative or worldview. Raspail directly influenced the emergence and popularity of the "great replacement" theory, which is the catchall theory cited by white terrorists.

But Bat Ye'or's conception of the problem — that European elites conspire with Arab elites to produce both subservience to Islam and the "great replacement" — directly influenced the Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik, who was motivated to provoke a decades-long civil war to stop the formation of what Ye'or called "Eurabia." Breivik, as well as the "great replacement" narrative, have inspired numerous white terrorist acts around the globe.

Returning to the American context, How did Steve Bannon and Breitbart spread their influence?

Bannon's principal contribution was to use Breitbart News to mix white supremacist ideology into the Republican Party and the Christian Right, and to heavily promote Raspail's "Camp of the Saints." In 2015 and 2016, Breitbart was the largest driver of ideological influence on the right.

How has this spread through the Trump administration?

The "Camp of the Saints" worldview largely shapes Stephen Miller's approach to immigration issues. Raspail's bottom line was that "the barbarians had to be repelled" either by violence or cruelty or both. Trump's immigration policy has been cruel, and as Adam Serwer noted, "cruelty is the point."

You also call attention to the Christian right's specific variant called "demographic winter," and argue that this has played a central role in evangelical support for Trump and his wall. What should people know about that?

The term "demographic winter" appears to have come from Don Feder, communications director of the World Congress of Families [a far-right, anti-LGBT Christian group]. He is the most prominent WCF official linked to the Tanton anti-immigration network and was apparently influenced by Bat Ye'or's "Eurabia" ideas, which circulate widely in conservative and right-wing Jewish circles.

In November 2005, Feder's view of Muslims in France reflected the worldview of Raspail and other "Eurabia" writers. Feder blamed the French riots of that year on "demographic winter," "lax immigration policies" and "brain-dead multiculturalism." Where "demographic winter" differs from Raspail, the "great replacement" and the Eurabia narratives is that liberal elite support for women's reproductive freedom and gay marriage are the principal culprits, in addition to massive Muslim immigration.

What resonates with conservative Christians and Christian nationalists is the idea that Christian (Western) civilization is under threat from nonwhite immigration, Christians are being persecuted in the West and around the world, and only a strong, authoritarian leader building a wall can save them.

Survey data supports my contention that white evangelical Protestants have a "Camp of the Saints" worldview: Seventy-eight percent favor strict limits on "legal immigration," 76% favor "building a [border] wall," 69% support a "temporary" Muslim ban and, 54% favor "preventing refugees from coming into the United States," according to October 2019 PRRI data.

The last section of your article deals with the emergence of the "Boogaloo boys" during the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests. How can we better understand them in terms of the longer history you've laid out? What lessons need to be learned?

The first lesson to be learned is that Donald Trump and local elected Republican officials, especially the so-called "constitutional sheriffs," have a much closer relationship to the armed wing of the Christian right. Bruce Wilson and David Neiwert have been tracking that.

The second lesson is that Trump is openly orchestrating armed demonstrations of force against Democratic Party governors and mayors.

The third lesson is that it is very easy to take off your camouflage fatigues and put on a Hawaiian shirt and pretend you just got concerned — but not before you spent around $2,000 on a rifle, tactical gear and ammunition. Journalists should stop being so credulous.

The last lesson is that claims that the "patriot" militia support Black Lives Matter protests are preposterous. The BLM protests are not simply about wrongful deaths at the hands of law enforcement — something a majority of whites can see and empathize with.

BLM is calling for reckoning, a "Third Reconstruction" of America — politically, economically and culturally — in the context of a deliberate confrontation with that racist, violent history. Even at the intellectual level of the "Never Trumpers," those potentially most sympathetic to BLM, there is a blindness or an inability to confront that larger American history and the smaller Republican Party history regarding racism. To think that "angry white men with guns" have thought it through is absurd.

What's the most important question I haven't asked? And what's the answer?

I do not know the answer to the question: "Why do scholars and journalists not consider the religious basis of America's long-term crisis of legitimacy in terms of politics and science?" But I would suggest that scholars and journalists have glommed on to the least important of Richard Hofstadter's explanations, "The Paranoid Style in American Politics," and ignored his more trenchant analysis in "Anti-Intellectualism in American Life," which focuses on the epistemological disruption caused by fundamentalist Protestantism. They also ignore Marty Lipset's and Earl Raab's use of the concept of monism in describing the right wing in "The Politics of Unreason." Those old guys were on to something.

Shares