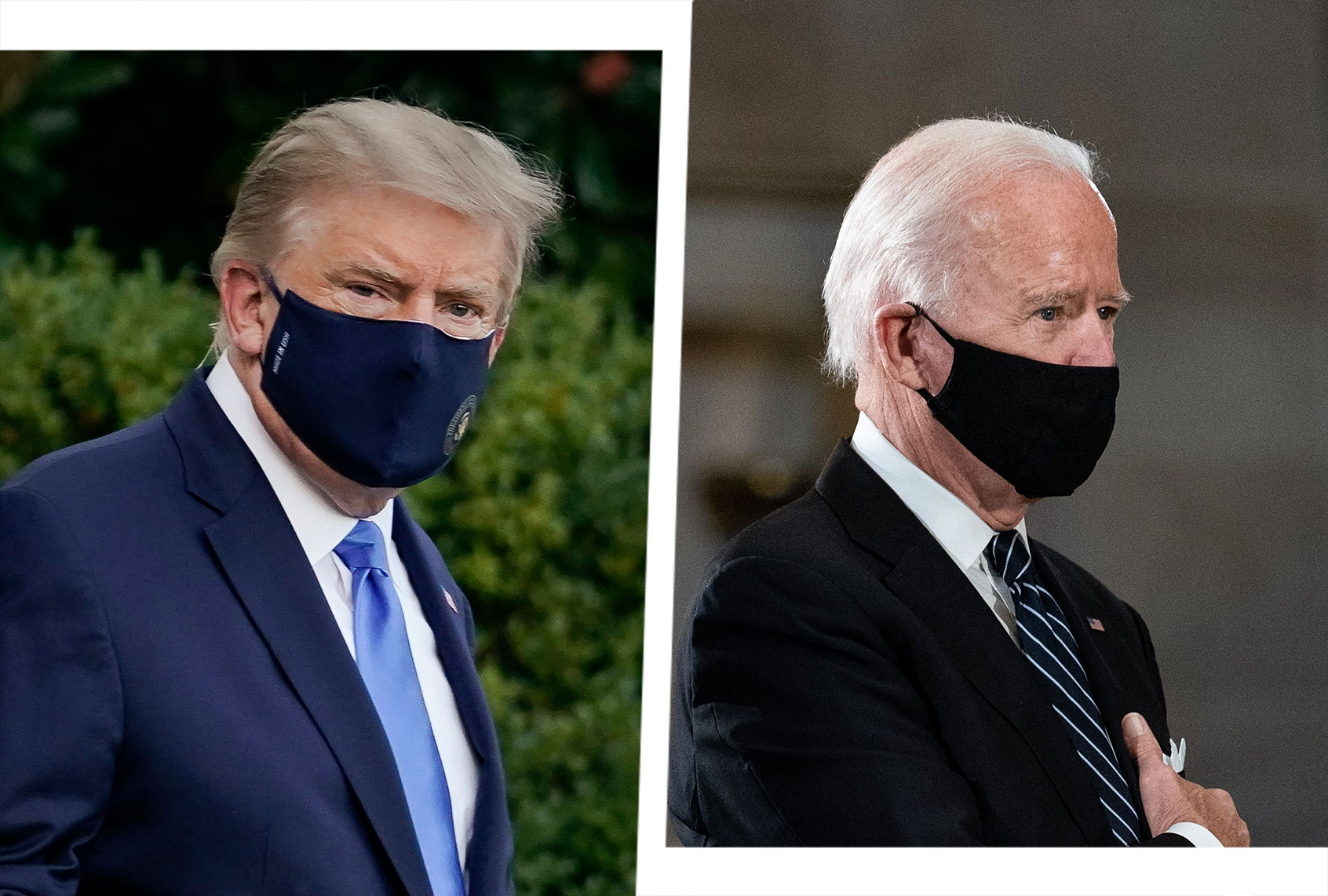

Both of the two major parties’ presidential candidates are septuagenarians; one of them, former Vice President Joe Biden, was recently in close proximity to a group of coronavirus-positive people, while the other, President Donald Trump, has contracted COVID-19 and is currently in the most crucial phase of infection. The two men’s age, and their proximity to a disease that kills about 12% of those in their mid-70s and older, has prompted many outside observers and legal experts to be forced to confront the unthinkable: if President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden dies before Election Day — or after the election but before the Electoral College convenes — will America enter a constitutional crisis?

As such a horrific scenario has suddenly entered the realm of possibility, Salon posed the question to several experts. The answer, as it turns out, is startling.

Harvard Law professor Laurence Tribe, when asked what might happen if Donald Trump were to pass before Election Day, warned that things could get messy. “The likeliest outcome of the death you’re imagining is that the Republican National Committee would convene in an emergency session,” and, utilizing the best legal advice available to them, would “decide how best to accommodate their respective deadlines for qualifying candidates, or more precisely the electoral slates committed to particular candidates, for the presidential election to be held this November 3,” Tribe said over email.

This process would be complicated, of course, by the fact that millions of Americans have already voted by mail — and their ballots cannot be retroactively changed. To accommodate this, and since it would be “lunacy” to ask people to resubmit their ballots, “my hope would be that the state chapters of the RNC would all agree simply to revise the instructions given to the electors committed at that time to the Trump/Pence slate in each of those States so as to conform those instructions to whatever new ticket the RNC were to choose – say, [Vice President] Mike Pence and [former United Nations Ambassador] Nikki Haley.”

Yet according to Tribe, that might not be the end of the matter. He noted that some electors could declare that they are only legally bound to support a Trump-Pence ticket and, if they do not want Pence to be president, resign rather than be compelled to cast their ballot for him.

He cited the July Supreme Court case of Chiafalo v. Washington, in which the unanimous ruling was that states can legally force electors to back the candidates they had previously pledged to support. That case came about because a group of Democratic electors known as the Hamilton Electors attempted to convince enough Republicans to abandon Trump after he won the 2016 election, so that he would not receive an Electoral College majority of 270 votes. That, in turn, would have thrown the election into the House of Representatives, where each state would have one vote to cast among the top three candidates. The Hamilton Electors had tried to convince Republican electors to back a member of their party who isn’t Trump, such as Ohio Gov. John Kasich or former Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Robert Alexander, a political scientist at Ohio Northern University, told Salon by email that the attorney who represented the Hamilton Electors at the Supreme Court had anticipated a scenario similar to the one that would unfold if Trump or Biden dies between now and the start of the new presidential term.

“Larry Lessig pointed out the potential problems associated with binding electors to vote for the popular vote winner in their state if indeed such a situation were to arise,” Alexander explained. “The Court didn’t appear to be moved by his concern over potential unanticipated consequences of a ruling removing elector freedom. They indicated that states could handle such a situation if it were to arise. However, I’m not convinced that all states that bind electors have attended to the problem convincingly.”

With the Hamilton Electors, however, the so-called “faithless electors” were trying to stop the election of a man they considered unfit to be president. In this theoretical scenario, they’d be trying to figure out what to do after being pledged to vote for a literal dead man.

“Predictably, many of the States will not have been sufficiently far-sighted to have enacted any legislative provisions on point, an eventuality that would trigger litigation,” Tribe explained to Salon. “Hopefully …. before November 3, the highest judicial tribunal of each such State would decide what to do on the basis of the background principles of that State’s laws, including its constitution.” He argued that the Supreme Court’s ruling to settle the controversial 2000 election, Bush v. Gore, could arise as precedent. As Tribe notes, there is “at least one possible reading requiring that disputes over the process of choosing electors be resolved strictly in terms of the directives laid down by the State Legislature, without resort to the State Constitution to change outcomes.” This would lead to a “legal morass,” Tribe explained, “but not necessarily a ‘constitutional crisis.'”

Rick Pildes, a professor of constitutional law at New York University, wrote to Salon about the possible outcomes if a candidate wins the presidential election but then died before the Electoral College can convene. Pildes thought that because of the nature of the electoral college, it might not be as much of a crisis as one might fear.

“The electors from that state would be able to vote for a different candidate for President,” Pildes told Salon. “There is the slight complexity that in around 16 states, state laws require the electors to vote for the candidate who won the popular vote; those laws impose sanctions for failing to do that, but most of those sanctions are minimal fines. So if this happened with President Trump, the Republican electors from states he won would vote for another candidate. If the RNC [Republican National Committee] – which is a 168 member body — voted to anoint another figure, the electors might well coalesce and vote for that figure.”

That scenario could be complicated, however, if the Republican Party cannot coalesce behind Vice President Mike Pence or some other alternative. If that resulted in no candidate receiving 270 electoral votes then, once again, the election would be thrown into the House of Representatives.

“The House votes one vote, one delegation, and a candidate needs a majority of the delegations to become elected,” Pildes told Salon.

There have only been two presidential elections that were thrown into the House of Representatives: the 1800 contest that elected Thomas Jefferson, and the 1824 contest that elected John Quincy Adams. Yet neither of those anomalies occurred because of a candidates’ death or incapacitation.

However, America has come close to that situation on one occasion. During the 1872 election, President Ulysses S. Grant ran for reelection on the Republican ticket against newspaper editor Horace Greeley, who had the support of both the Democratic Party and a splinter faction of the Republicans. Greeley died after Election Day but before the Electoral College could meet.

That could have resulted in a constitutional crisis had Greeley won. Fortuitously, Grant won in a landslide, so there was no constitutional crisis and no test of the presidential voting system. Ultimately, Greeley only won 66 electoral votes to Grant’s 286 electoral votes, and 63 of Greeley’s 66 electors decided to support one of several other Democrats when casting their vote.

“When Congress met, they decided not to count those votes since he was dead and thusly ineligible to serve,” Alexander explained. “It would seem to me that a precedent was set. If electors are forced to vote for the candidate who won the vote in their state and that candidate dies before they meet, then I’m not sure the states with binding laws have adequately dealt with such a possibility.”

He added, though, that “fourteen states have laws that remove an elector for not voting as anticipated. Among these, only Utah’s statute permits an elector to break their pledge in case of a death of a nominee. Arizona, Colorado and Maine require electors to vote for the popular vote winner in their respective states (or districts). This would seem to force them to potentially vote for a deceased candidate if they were to die after the election and before they met.”

Because electors could argue that they are actually bound to vote for their party’s nominees, they might be able to sidestep accusations of being faithless electors if their party chose a different nominee.

Even so, Alexander explained, “no doubt, legal challenges would ensue as a result.”

If there is one thing we can say for certain, it is that any scenario in which Trump or Biden dies before the Electoral College casts its votes would be hell on the electors themselves.

“This helps justify me putting aside my life for a year to try to fight for this country,” Hamilton Elector alumnus Chiafalo told Salon about his battle to allow electors the autonomy to vote their conscience. “It’s almost been completely proven that we were right to fear exactly what we thought was coming. As for electors this year, I feel horrible for them because if they make the wrong decision — based on the far-right of this country — their lives will probably be forfeit.”

He added, “They’re going to get more death threats than I did, and I got hundreds. So if I was one of the electors. I’d be terrified. I’d be buying guns and a bulletproof vest.”