This is the first of two parts about the firing of Warren Whitlock. Next: The Pentagon official comes under a second investigation while someone else gets his job.

Warren S. Whitlock enjoyed a remarkable career as a diversity officer at the federal Transportation Department, winning victories for poor communities of color that his superiors thought impossible. There's even a documentary film about his success in getting municipal bus service for a Black neighborhood in Beavercreek, Ohio, that had been bypassed intentionally.

In its waning days of the Obama era, the Army chose Whitlock to become one of its highest-ranking Black civilians. His task: resolve diversity issues that had languished for years, some since George Herbert Walker Bush was commander-in-chief nearly three decades ago.

After Trump became president, Whitlock encountered a very different situation. He found himself reporting to Diane Randon, a white woman who defended in writing keeping the names of Civil War traitors on streets at a U.S. Army base in Brooklyn. According to Randon's Linkedin profile, she is the Army's assistant deputy chief of staff, G2 (military intelligence).

Behind Whitlock's back, testimony later revealed, she denigrated him. Twice the boss ordered unauthorized investigations of Whitlock. In private, it was learned later, she maneuvered to get rid of Whitlock whose title was "Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Diversity and Leadership."

A Whitlock subordinate who has long been friendly with his boss called him vile names behind his back, testimony would later reveal.

Whitlock, a Princeton graduate with a master's degree from Columbia, had a strong performance record.

The Army abruptly fired Whitlock in January 2019, even though he had a pending racial discrimination complaint which is supposed to prevent retaliatory actions by our government. The way Whitlock was fired denied him an opportunity to correct an administrative mistake he made. The firing order also left Whitlock without his pension or health insurance.

Whitlock's dismissal, reported here for the first time, could be seen as just one unfortunate example of mistreatment of an employee. But a DCReport investigation shows it is much more. It is a case with broad implications for our entire federal workforce. It reveals the effects of the Trump administration's efforts to make the highest civilian ranks of our government as white as possible.

Trump's never-settle policy

Whitlock, 62, faces a tough fight because in May 2018 Donald Trump issued an executive order that discourages settlements between federal agencies and employees in job discrimination cases.

Even if an employee wins, proving at trial that they were wrongly disciplined or fired, Trump's order prohibits removing negative information from a personnel file. That makes advancement to a bigger job almost impossible. It also undermines the integrity of government records.

In addition to that directive, Trump demonstrated his scorn for people of color and diversity in the federal workforce when he signed another executive order in September. That one ended diversity training in our federal government, including the military branches, asserting this was necessary to "combat offensive and anti-American race and sex stereotyping and scapegoating."

The order said any training that suggests whites have dominated society or acted other than in a spirit of equality "perpetuates racial stereotypes and division and can use subtle coercive pressure to ensure conformity of viewpoint. Such ideas may be fashionable in the academy, but they have no place in programs and activities supported by Federal taxpayer dollars."

Whitlock's firing also sent a signal to federal executives who are people of color: Be afraid for your jobs.

Fear is a performance killer. But fear is what Trump spread in his faux reality television shows for 14 seasons where contestants anxiously tried to escape being told, "You're fired." Many of those "fired" actually did good or even their best work, as close observers of the show have noted.

So, what was the conduct that justified removing Whitlock with his outstanding record of accomplishments? What justified humiliation instead of, say, letting the man retire? Or just giving him a talking to and moving on?

One Keystroke

Whitlock's unforgivable offense was punching the wrong key on an Army computer. One keystroke.

That mistake sent a draft performance evaluation of a subordinate from Whitlock's desktop work computer to the Army's clunky personnel software system known as AutoNOA. Whitlock should have sent the final version.

No other Army civilian has been fired for a similar "administrative error," specifically for "accidentally uploading a wrong document."

We know that damning fact only because the administrative law judge hearing Whitlock's civil rights case seeking to get his job back extracted it from an Army witness. Indeed, the 2019 hearing record shows only one other person who made a similar mistake was ever disciplined. That person was allowed to retire.

You might think the way to fix the problem of sending the wrong file internally would be to just pull it back and send the final performance evaluation. You might think that someone who makes a keypunching error ought to be given the opportunity to undo the mistake, especially if they have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD. Federal law is supposed to protect workers with disabilities, including ADHD.

Unauthorized Investigations

You also might ask whether such a mistake is even worth putting in anyone's personnel file. And it's just as reasonable to ask why the Army isn't investigating the woman who got Whitlock removed over that single keystroke since she orchestrated two unauthorized investigations of Whitlock, a breach of an Army regulation that seems far more serious.

But this is the Trump administration, the most racist since Woodrow Wilson more than a century ago. Despite Trump's claims of being "the least racist person" of all time, the president talks in racist terms all the time. He has a half-century record, documented informal proceedings, of discriminating against Blacks, women, Asians and Puerto Ricans.

Trump civilian appointees in the Army seem intent on doing and spending whatever it takes to make sure Whitlock stays fired even if it means granting retroactive approval for unauthorized actions that harmed him.

The costs of fighting Whitlock's case are relevant because Trump often boasts about how much money he saves taxpayers through random cuts in government services—like the pandemic national security team that former President Barack Obama had installed in the White House.

But when it comes to taking maximum advantage of any opportunity to rid the federal civil service of a Black person in a high position, especially those who achieve results, the de facto Trump administration policy is to spare no expense.

That Whitlock transferred to the Army during the Obama years was also a strike against him, at least in the current administration, which is determined to wipe out every success, large or small, by America's first Black president.

Ghoulish Legal Algebra

In Whitlock's case, there's also a ghoulish algebra to the Trump administration's refusal to settle. Before his firing, doctors told Whitlock that he had a form of blood cancer that disproportionately afflicts Blacks.

Meanwhile, the Army is stalling (which Trump would applaud) and has made a false claim in trying to get his case transferred away from largely black juries in Washington to conservative, white and government-friendly Northern Virginia.

That's Trump & Co.'s ghoulish algebra—delay forever.

Trump's merciless policies were taught to him by his longtime personal lawyer, the man he calls his second father, the notorious Roy Cohn. As consigliere to Mafiosi and fixer supremo for Manhattan's and Washington's political and economic elite, Cohn taught Trump that the law isn't about justice, right and wrong, or even rules. It's about how those with no shame can lie, cheat and steal with impunity, something Trump says in his book The Art of the Deal.

Cohn taught Trump never to apologize, never acknowledge an error, never settle; delay, delay, delay and always attack, attack, attack.

Throughout his career, Trump has used stalling tactics to run up the legal bills of the other side hoping they would run out of money, miss a filing deadline or go broke. We are witnessing that right now as he fights a subpoena issued to his accounting firm for financial records, a case he has taken twice to the Supreme Court.

There are also the more than two dozen women who have accused him of molesting or raping them who are encountering agonizing stall tactics. Trump makes people pay a price for being what Southern racists call B

lack people who don't know their place — uppity.

This means the government's lawyers aren't going to settle job discrimination cases, even when the facts against our government are, as with Whitlock, overwhelmingly against our government.

Obliterating Obama's actions

"From the time the Obama people left in January 2017, and the Trump people came in, I was under attack by my new boss," Whitlock said during interviews for this story.

His new boss was Diane Randon, a 30-year civilian in the military.

"She was openly hostile from the start," he said. An outside contractor confirmed that during a multi-day hearing of Whitlock's case before a Merit Systems Protection Board administrative law judge in 2019.

The contractor, who advises the Navy and Army on diversity issues, testified she was surprised by Randon's open animosity toward Whitlock during a meeting held shortly after Trump's inauguration. Randon just replaced Whitlock's boss.

The consultant, Renee Yuengling, said she only recently met Randon.

Yuengling testified that during the meeting Randon tried to "trap" Whitlock into saying something positive about one of the preferred diversity policies of Obama's outgoing secretary of the Army, Eric Fanning. That matters because in the Trump administration anything Obama did was bad and must be undone, be it the Affordable Care Act or something as relatively minor as a positive comment by one civil servant.

Yuengling declined to comment on her testimony.

"Diane wanted me out of my position from the beginning of her detail to Manpower & Reserve Affairs Division," Whitlock told DCReport. "I spent the next two years defending myself from a series of spurious allegations instead of being allowed to modernize that office and its mission."

Randon did not respond to multiple messages seeking her side of the story. The Army also repeatedly declined official comment.

Former Army secretary Fanning was among those who praised Whitlock in interviews. "Warren is a terrific employee," but faced resistance from top to bottom, Fanning told DCReport.

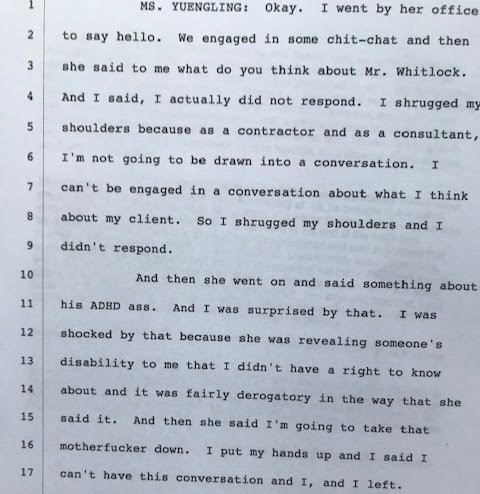

Renee Yuengling's testimony

Fanning said modernizing the Army's approach to diversity issues was difficult. "Even when I was there, we were getting push-back" from high-level employees as well as the regulars who had dealt with the Equal Opportunity Office. "We were promoting diversity as a positive, not punitive outcome, trying to get more diversity into the higher ranks which were and are still very white and male," Fanning said.

Fanning wanted the Army to think about diversity the way the corporate world has come to embrace, as a way to increase efficiency, improve effectiveness and grow profits. "We see diversity's goal as enhancing efficiency of the unit, performance in the command and therefore the overall success of the mission," Fanning told DCReport.

One of Whitlock's predecessors in the Army diversity office said the panel that chose Whitlock should have instead named someone with Army experience, who knew the "culture."

But Karl Schneider, a member of the Army panel who has 44 years of experience as a soldier and Army civilian, said most of the panelists "wanted someone outside the Army culture."

Other panelists gave lengthy interviews about what they said was a need to invigorate the diversity office and their belief that Whitlock's track record demonstrated that was the best person for the job. DCReport is not quoting them because we avoid using unnamed sources.

Whitlock agreed with Fanning that his problems came from below as well as above. "The deputy I inherited, I learned, was an acquaintance of Diane's for more than 20 years. They acted like old friends… Now that I've seen the documents and emails, it looks like the two of them worked in concert from the beginning to undermine me and my mission."

Both Randon and Whitlock's deputy, Seema Salter, testified that although they knew each other for decades and attended professional meetings together, they were not close friends.

Salter was certainly not a friend of Whitlock, her boss. In December 2016, Salter unloaded on Whitlock in unusual terms to Yuengling, the diversity consultant.

Salter "said something about his 'ADHD ass'," Yuengling testified at the merit systems board hearing.

Violating a confidence

"I was shocked by that because she was revealing someone's disability to me that I didn't have a right to know about, and it was fairly derogatory in the way that she said it," Yuengling testified.

"Then she [Salter] said 'I'm going to take that motherfucker down'," Yuengling testified.

Yuengling said she quickly left to avoid being part of a negative conversation about "the client." Salter testified that she had indeed used "motherfucker" to describe Whitlock.

Whitlock didn't learn about that encounter until much later. Nor did he know that around March 15, 2017, less than two months after Trump assumed office, that he was secretly placed under investigation by the Army.

Randon had arranged for a 15-6 investigation that both Army and Army civilians dread, as we shall soon see. The number refers to an Army regulation.

Justification for firing

What was the justification for that investigation: Theft? Revealing secrets? Having sex in a Pentagon office? Using slurs?

None of those. It was about one of several annual awards that long-timers in Whitlock's office handled to honor the Army's achievements in diversity.

Several months after Whitlock moved from the Department of Transportation to the Army in late 2016, one of Whitlock's assistants, Margo Barfield, asked him to nominate someone for the Stars and Stripes Award at the upcoming Black Engineer of the Year Award (BEYA) conference.

Every February, American military officials from around the globe fly to Washington to attend the annual BEYA meeting celebrating African American achievements in science and technology in the military and defense industries.

Whitlock, a member of the Senior Executive Service, felt that lower-level people should handle such conference matters.

"I was running around working on things like expanding religious rights and using resumes without photos attached for promotion applications. I was like, 'You're kidding me: I'm involved in awards?' " Whitlock said.

Barfield, his assistant, suggested an award for Lt. Col. Cynthia Lightner, who was Whitlock's executive officer, testimony showed. Barfield told him that Lightner was very experienced and was planning to retire later the next year. The award would be appropriate as her send-off. Whitlock agreed. Barfield began the paperwork.

Protocol questions

Soon after the conference ended Randon began asking about the awards. What protocol had Whitlock followed in choosing Lightner for the Stars and Stripes?

That question became the focus of the first of two unauthorized investigations. It was unauthorized because in 2015 the secretary of the Army under Obama issued an order that any investigation of high-level civilian employees known as SES for Senior Executive Service first required "written approval" from the Civilian Senior Leader Management Office.

That approval was not sought, but later a Trump appointee applied a form of backdating to hide this failure. Whitlock knew nothing of the investigation.

A two-star general wrote the single-spaced 10-page investigative report in May 2017. Whitlock and his lawyer David Shapiro would not see the report until 18 months later, not long before his firing.

General Leslie Purser was critical of Whitlock, concluding that he "failed to effectively lead this organization," "lacks good judgment" and is "naïve."

Formal reprimand suggested

"I would suggest more training on effective leadership, but I do not believe he would comprehend the message," Purser wrote. The general recommended that a formal reprimand be placed in Whitlock's personnel file.

Purser wrote that the Black engineer award selection board had not been planned properly. But there is a revealing twist in that finding. It is one showing how a bureaucratic knife was thrust unseen into Whitlock's record, a crucial detail that did not escape the general's notice.

"This impromptu board selection was a result of delayed processing of the memo requesting the board of senior-level officials. The Form 5 for the selection was signed by Ms. Barfield on 8 Nov 2016, by Ms. Salter on 1 Dec 2016,"… Mr. Whitlock did not realize it was there until 12 December…

"Ms. Salter accuses Mr. Whitlock of stalling on this signature, yet she had the memo for several weeks prior to submission to the front office and did not identify that fact in her comments to me," Purser wrote.

A set-up?

That could be interpreted as Salter setting up the boss she had denigrated in foul language.

The general continued in detail about the awards and the surrounding activities, including the role of Salter, who had been transferred to Fort Belvoir in Virginia, apparently to her dislike.

Much of the report seems like an analysis of how many tiny bureaucratic games could be played on the head of a pin. It detailed such minutia as which of the Army's many diversity offices across America gets to produce the Black engineer awards conference.

Purser's report found Salter "removed herself from awards process out of frustration and rebellion. It is noted that Ms. Salter is inflexible and prescribes to the way it always used to be." The general also wrote that Salter "is resistant to change and is very critical of Mr. Whitlock."

Salter told DCReport she did not want to comment on Whitlock or his case. Diane Randon did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

A troubling diagnosis

Whitlock had other problems in the spring of 2017 that he was unaware of until late 2018. Unbeknownst to him, Randon asked her staff to start keeping a time and attendance record on Whitlock, according to testimony by a human resources official.

That witness testified that "Whitlock was [the] only person that Randon asked about time and attendance records," said David Shapiro, Whitlock's attorney. "Warren's an Assistant Deputy Secretary, he's SES, and Randon wants a secret time and attendance chart on him," an incredulous Shapiro said. "How about: He's the only high-ranking black male in Randon's office," the lawyer said, adding one word: "Racism."

Whitlock, meanwhile, had been feeling weak and sick for months. After medical tests, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that disproportionately affects African Americans.

He told Randon about his illness, including that treatment would affect his work schedule. He also disclosed that he would participate in a clinical test of a new drug. That would require trips to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., a dozen miles from his Pentagon office. He said he promised Randon that he'd make up all his lost time even though he had more than enough sick leave built up to cover his absences for medical treatment.

Defending army traitors

A few months later, in August 2017, Randon landed in the news, defending the naming of streets on an Army base in honor of generals who violated their oaths, joined the Confederacy and waged war on the United States. Members of New York's Congressional delegation wrote the Army asking that street signs with the names of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn be changed.

Randon wrote the Army's official refusal letter. The streets were originally named after Confederate generals in "the spirit of reconciliation" and to honor soldiers who were "an inextricable part of our military history."

"After over a century, any effort to rename memorializations on Fort Hamilton would be controversial and divisive," Randon wrote.

A number of Pentagon people, black and white, told Whitlock they were embarrassed by Randon's letter, especially because of her high-level position in the diversity area.

Performance reviews

In late August, Whitlock made the mistake that got him fired, that single erroneous keystroke. Randon treated it as ammunition, firing it to kill Whitlock's career.

The mistake came as Whitlock prepared annual performance evaluations for four subordinates. He had similar experience in his previous job at the Department of Transportation but said, "I was new to the Army job grading system."

That system had a quirk which would become important in his discrimination case. The Army has two civilian grading systems both with ratings of 1 to 5. For some employees 5 is the best score and 1 the worst. But for others it's the opposite.

Whitlock felt a bit overwhelmed at the Pentagon.

"I was trying to juggle finishing the evaluations while also preparing new job descriptions for my staff for the up-coming performance year, which we'd been asked for. I did not have a confidential executive assistant to perform these administrative tasks on my behalf. In hurrying to get the final job evaluations to the management support team, I hit Send."

What he sent was a draft, not the final version, to the Army's personnel software system called AutoNOA.

In a normal situation, that's called a mistake or a clerical error, and it happens every day to thousands of people. But the draft evaluation was of one person who had privately declared in vile language her intent to get rid of Whitlock — Seema Salter.

This is where that quirk in the personnel system becomes important. In the draft version of Salter's evaluation, Whitlock had rated her on the wrong scale, something he fixed in the final version, the one that he mistakenly didn't email forward into the AutoNOA files.

Holiday weekend

On Sept. 1, 2017, the Friday afternoon before Labor Day, Salter emailed Whitlock asking why her signed paper performance evaluation with a rating of 2, which means exceeds expectations, was lowered in the electronic version in AutoNOA.

Whitlock didn't see that email until Tuesday, the morning after the holiday.

According to Whitlock's testimony on that Tuesday he immediately called the personnel office and said he'd sent the wrong document. He told them it was a draft. His printed draft had whiteout and other jottings indicating clearly it was not a final version.

How to retrieve that document and send the correct one? Whitlock asked. The answer: that's difficult-to-impossible because AutoNOA is a clunky system not designed to allow correcting mistakes.

"I was told it was very hard to get something out of AutoNOA. Basically: good luck," Whitlock told me. "I realized I'd have to fix this quickly."

Stories diverge

It had not been fixed by the next day when Randon called him into her office. Why, she asked, had he altered Salter's evaluation after they jointly reviewed the draft and agreed on a higher grade. Here the stories Randon and Whitlock tell diverge.

Whitlock's position is that he told Randon it was an accident, that it would be easy to see that because of the whiteout and scribbling on the paper draft. He testified that he told Randon he was working on fixing the mistake before she inquired.

Randon testified that Whitlock told her he did not want to give Salter a high number and, without telling her, lowered the score after she had signed off on a highest grade. Randon testified that she tried to get Whitlock to sign a statement admitting that he had deliberately altered Salter's evaluation. That would be a violation of the regulations and could justify termination. Randon said Whitlock refused.

For the next few days, Randon tried repeatedly to get Whitlock to sign the incriminating statement. Randon testified, "I chased him to his office. I mean, I was – I was stalking him."

Whitlock refused to sign on the advice of Army lawyers. "I asked the deputy general counsel of the Army what to do and he said 'sign nothing'." Whitlock followed that counsel.

Whitlock tried to get Salter to sign her new evaluation with the higher performance rating she wanted and that they had agreed to originally. Salter refused. Later Randon would testify that she advised Salter not to cooperate with Whitlock's effort to correct the record until she had talked to high-ups. Then a few days later she took what she called an altered job evaluation to an inspector general.

Shares