Democrats were hoping for a massive repudiation of the Republican Party under Trump, and a chance to strike out in a far more progressive direction. What they got instead was a much more muted victory that took days to unfold, and is limited to the presidency — at least for now.

But amid the immediate disappointment of Election Night and the exuberance that followed Joe Biden's eventual victory, the situation in the South stood out: the difference between the polling averages and the initial returns in Southern states like North Carolina and Georgia was about three points, compared to seven or more in states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio. Well before Biden inched into the lead in Georgia, and before it was clear that both Senate races there would require runoff elections, there was cause for hope in that region, foretold in a tweet from Angie Maxwell, co-author of "The Long Southern Strategy" (Salon author interview here):

The Long Southern Strategy was a top-down effort to turn the South red that took 4 decades. Turning it blue will take a grassroots bottom-up effort over several cycles. What you see now in TX, GA, & NC is years of blood, sweat, and organizing.

I couldn't think of a better way forward than to ask Maxwell to expound on what she has seen unfolding, especially considering her uniquely insightful analysis of how the "Long Southern Strategy" worked, and how it transformed American politics nationally — and not just in the South. If anyone could shed light on how that strategy can finally be reversed — and how it already, slowly, is being reversed — I knew it would be her. As usual, this interview has been edited for clarity and length.

So Joe Biden has won the election, but Democrats fell short of hopes and expectations, most notably in the Senate. But you're from the South, and the trajectory of Democratic fortunes looks different from that perspective. Before the election, you tweeted about what it would take to turn the South blue and begin to reverse the "Long Southern Strategy." Do you still feel hopeful and determined?

I do! And I'm not saying that in some kind of Pollyanna way. I have to tell you, when you live down here in these deep red states and you study this as your specialty, to hear that the polls are closing in North Carolina and Georgia and Texas and it's too close to call — It's not just immediately red — I don't think people realize how hard that is to pull off in a pandemic, with the levels of voter suppression we've had and the gutting of the Voting Rights Act. It's pretty remarkable.

Texas is moving blue, and I think North Carolina and Georgia are there. What you're going to see in North Carolina is some split ticketing — because that is often what happens when a state is flipping, for a couple of cycles. People are like, "I kind of like this Democratic governor, but I don't know nationally." They feel like somehow they're right in the middle and they're kind of balancing.

It happened in Arkansas for years, so that doesn't surprise me. The big factor I would say is we've just never done this with 80 to 90 million absentee ballots. I watched in Arkansas, specifically — and this is true in lots of different states — people really nervous about coronavirus, because it got real big here in the summer, requesting an absentee ballot and then hearing some of the static about the Postal Service delays, which got been pretty bad here, and then saying, "You know, I think I'm gonna go in person," and not realizing that there are things you have to do to be able to do that, that are state-specific. So, I was worried — when we're talking about margins that are tiny — I was worried about that.

There was an effort in Georgia to reach people whose ballots were considered provisional and have them cure the ballots — there are different state laws about how many days you have, who has to be the person who reaches out, all of that. But I think there was some misinformation — nobody's fault, just circumstances—that might have made a little bit of difference in a few places. It's reasonable to think we could've seen North Carolina go blue if it weren't for some of that.

So overall, you see the results as promising?

That's promising to me. Don't get me wrong, it's frustrating. You want it to happen tomorrow, but I know there's been an effort for 10 years in North Carolina. They been working at this and organizing for 10 years. Virginia, 12. Georgia has been about four. Texas has been about four. It builds on the cycles where you have good candidates and you have competition all the way down the ballot. You have to have Democrats running in as many state rep seats and state assembly seats as they can, for everything, all the way up, because it lifts the top of the ticket.

That takes infrastructure and organizing that no matter how wonderful a candidate is — say in Texas, Beto O'Rourke: charismatic and engaging — without the infrastructure, you're already going with a handicap in the South from voter suppression, It's hard. I know the Democratic database has been getting better in the South. For years it's been like a blank slate. If you don't have competitive primaries and things like that, you just don't know where people even lean. So the more competition there is, the better campaigns are at reaching voters they need.

What would you add in terms of how things are turning out? Anything more you'd like to say about any specific races?

I feel like we very much had an absentee ballot strategy and messaging that switched to "Go vote in person." It's hard enough to message once about voting. It's really hard — especially in Southern states, where we don't have same-day registration — to do that. It's really tough. Maybe a little more effort or just streamlining that could have helped, but hindsight is 20/20.

I'm pleased in terms of the candidates that ran — with the exception of [Cal] Cunningham and what came out about his personal life. I think Jamie Harrison is an exceptional candidate. Joyce Eliot, who was running for the Arkansas 2nd district in the U.S. House, a 30-year retired schoolteacher and state senator, an excellent candidate. I think the quality is high and I think that's what upsets people, what's disappointing, is they are pulling some amazing talent and running it, but talent alone cannot replace infrastructure, data and get-out-the-vote history.

But it can help build that for the future.

A hundred percent! You're not starting at zero in Texas. You're starting from where Beto O'Rourke left off. I've been watching today with people going into action in Georgia, that Fair Fight network is serious. There's smaller and newer groups here [in Arkansas] that are working hard to get those ballots counted in most statehouse races. If we didn't have those organizations here, we'd be leaving that to state rep candidates and their campaigns staff. That's hard.

States like North Carolina and Georgia came much closer to meeting expectations, as reflected in polling averages, than Rust Belt states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio. Setting aside the polling problems, what lessons should Democrats nationally take away from these results?

Honestly, we just have to have targeted and tailored strategies. What works in Georgia, the coalition you're trying to build there, is not the same coalition you're trying to build in North Carolina necessarily. In Georgia it's really the urban areas and the African-American vote that's changing things, and in North Carolina, it's a high levels of education that are changing things. South Carolina has such a large African-American population, it needs a strategy that looks a little more like Georgia's. Texas is all different, because you have a Latino vote that a lot of scholars have been saying is not a monolith and people have to pay attention to country of origin and religious values and that the messaging's got to be real specific. I think sometimes we just think "South," and I think we really have to break that up. There's a couple of states that might be similar, but it's different than like the Rust Belt.

How should the party address that?

I think a lot of times in the South, organizers came from outside in the past, but you really need organizers inside, you need people who know that state backwards and forward and know its history and can be specific and local. One thing that North Carolina figured out a couple years ago when they elected the Democratic governor is that teachers and education was a messaging issue that was helpful for Democrats to pick up people they needed. That could be very different somewhere else. You can't make assumptions about how people feel and think.

For example, you look at places like in Arkansas a couple years ago and Florida, where they had had minimum wage on a ballot initiative. In Arkansas it passed with like 77% of the vote, and we couldn't get Republican legislators to take it up. When you start seeing that you realize where people are on certain issues and there's a disconnect with the party brand. That is something that has got to be addressed.

I wrote a piece for 538 right before the Super Tuesday primaries about Democrats in the South, and how they are different from Democrats outside the South. One thing we tend to stereotype is black voters in the South being moderate, or maybe even socially moderate, but I don't think that's it at all. I think they're pragmatic. Bernie [Sanders] did not do well in those Southern primaries, and it's not necessarily because people disagree with Medicare for All. It just seems like such a reach from where they are. And when you look at where Bernie did well, it was in blue states where the message he's giving seems like the next step, or seems doable. A lot of times in the South it may sound wonderful, but people who live here and know what it's like, it doesn't seem possible. It doesn't seem pragmatic, and I think that pragmatism is important to Southern voters.

Is there anything more specific to this campaign you'd like to add?

I think one thing that is a little bit of a missed opportunity was in terms of the coronavirus, not just touching on how badly it has been handled, but also what is the plan, instantly? What is done in month one? Is it to invoke that National Defense Authorization Act and quick mandatory testing in schools, so all the kids can go back to school? How fast can that be done? That kind of pragmatism where people go "OK, that would be better. Yes, I like that," instead of just like why it's all been so bad — and it has. But people are kind of used to that, that live in these red states, and they have been left with no plans, even by their local government.

A lot of people just bought into "This is not so bad," or "It's getting better," because it's hard to deal with it emotionally every single day, the uncertainty. I watched parents agonize over the decision of sending their children back to school in August and a lot of times it's like the second they made that decision it's like they did not want to think about it anymore. Because there really is no option and when they had to go back to work, or they always were working, they just can't live thinking, "Am I endangering my family?" So they need to kind of believe it's getting better, and our governor here stopped doing his daily press conferences on it and I think it was exactly for that reason. People just kind of don't want to hear it.

People can see the numbers going up, but when you have no control, no way of ending the uncertainty of it, that's a hard thing — for people to not tune out at a deep place. So, I'm just wondering if a little tweaking of that message would've helped.

That makes a lot of sense. People involved in politics get caught up in a vortex of message-thinking versus what you were just talking about: What it's like for ordinary people, and how they are coping with everyday life.

Right. A lot of people just kind of give up. They care, but they don't know what else to do. There is no plan in place, they don't see it getting better, and they can't live with that emotional turmoil every day, So being reminded of it and not being made empowered by it — like, "This what we're going to do. You're going to wear your mask, you're going to do this until this date, and when we get in office, this is what we're going to do in the first month." That kind of reassurance I think can be attractive.

I think what's upsetting to some is that they just cannot believe that with all of the things the Trump administration has done and said, that people would still vote for him. We know that in the South. People have been living with that a long time. And so that does not surprise me. It surprises me in a positive way that so many people organized to fight against it, and make some states down here really competitive.

Going back to your tweet that caught my attention. Your book discusses four things about the Southern Strategy I'd like to ask about: The first two are that race alone does not explain the Long Southern Strategy, that gender and religion were equally important, and second, that all were involved in shaping a defensive definition of identity.

Most people look at who's voting Republican in the South and say, "They're voting against their economic self-interest. That's so irrational for low-income people." But when you live with the kind of poverty you have in the South — not even hardcore poverty, but just no mobility, no opportunity in rural areas where the population is declining and education's so expensive. When you say they can get healthcare on an exchange and the deductible is $10,000, it might as well be $10 million. So when you quit thinking that government can do something that's really going to change your life, because you're below that curve that maybe some help can help tip you over into a little better quality of life — when you're below that, then you tend to default to values and identity.

So the Republican Party over the years has hit all three of those things. We also make the assumption that people are all three, but it's a very small percentage that feel excessive racial resentment and excessive modern sexism — which is a distrust of working women and support for hyper-masculinity — and then Christian nationalism, which is of course very different from being just religious. And a lot of people are one of three or two of three. I think lumping all of that together is where Democrats kind of miss the mark. People that are one of three can sometimes be reached.

But there's more to the story, right?

There's also a really weird thing going on with the branding. I've said before in the book it wasn't just the policy positions that the GOP took over time that won over some of these voters. They really adopted the Southern style, which is large rally-based campaigns, it's a politics of entertainment, and that to me is one of the most destructive aspects. It was V.O. Key in 1949, in his classic work "Southern Politics in State and Nation" who said the worst part about one-party politics is that it becomes a facade in the South, a kind of politics of entertainment and not a contest of policy ideas.

And that's so true when we see ballot initiatives pass at 70%, and the brand and the policies don't match up, they're not associated with each other. And that is because you don't have that kind of two-party competition, you just have kind of one umbrella and who gets the most attention, who can entertain the most, or who can be the most outrageous, get the most headlines. That has a long history in the South and Trump is kind of tailor-made for that.

The Republican Party kind of adopted that style. It's very much the politics of entertainment, it's also the us-versus-them style. People sometimes call it positive polarization, which is you do not define yourself by who you are, you define yourself as a candidate by who you're not. So, "I'm not a Nancy Pelosi, AOC whatever." Creating that kind of dichotomy, that has a long history in the South too, it resonates here. And in doing that, the Republican Party rebranded itself in the Southern image in a way that feels very familiar to people. And like politicians for decades from the region — even though Trump is from New York, he seemed like that. Because the Republican brand gives them that option already.

So Democrats have to think about how to brand themselves in a way that speaks to Southerners at a kind of a value level. We also find that Southern whites who are Democrats who grew up in the South, who are not transplants, when they become Democrats. we find that they go really far left — men and women. Then they're fighting within the Democratic Party about the brand because one group is really left and likes the national brand and even pushing it further, and the other is going, "But we've have to win more people over, we have to kind of be in the middle." And that is not something that's been reconciled.

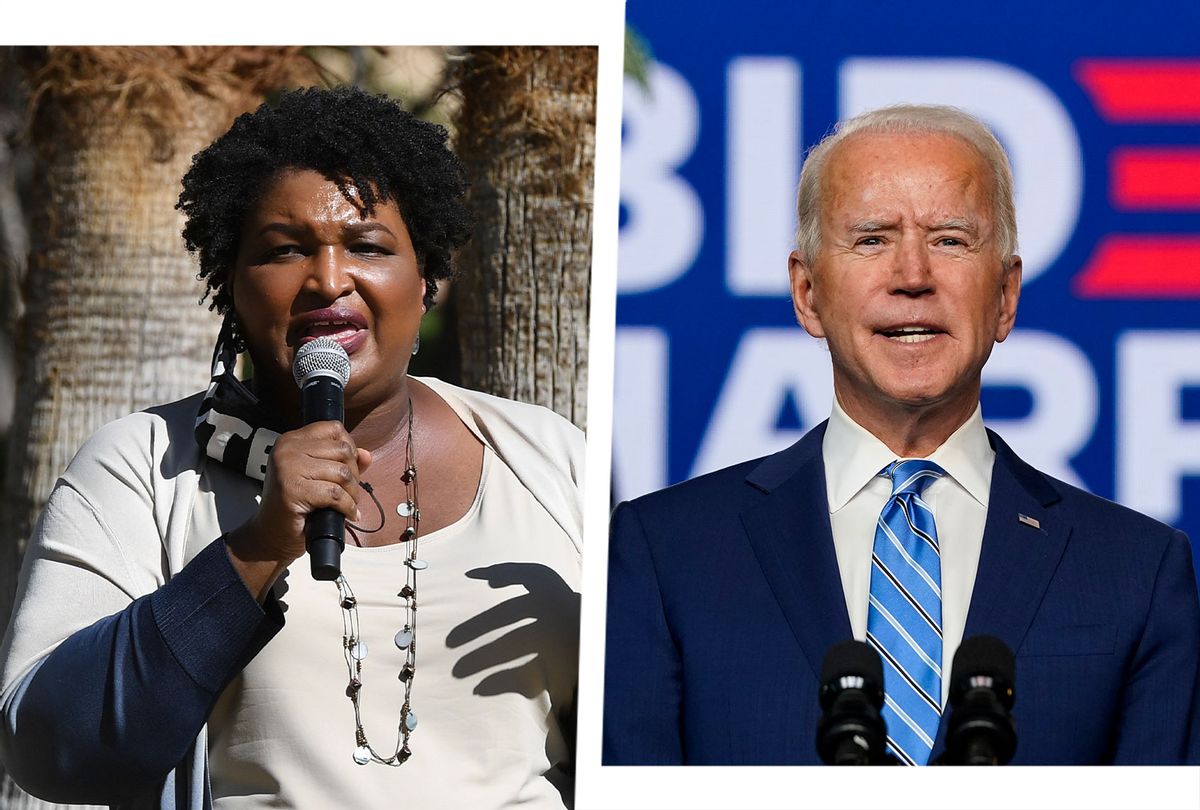

Is there anything you can point to in the organizing now that's been successful in terms of forging a new sense of identity? I thought that Stacey Abrams' focus on voting rights was one possibility — where the Southern Strategy was focused on defensive identity, her focus on voting is about a proactive shared identity: Together we can create a different future. It's a big-tent identity people can share who may have different specific goals in mind, but they work together.

Absolutely! I think that is perfect example. One example — people don't think about it a lot because of the NRA's stronghold in the South, but Moms Demand has gotten people elected in the South in statehouse races by appealing to moms who are reasonable, who are saying, "Hey, we all care about our kids, and we want best practices." You know the Moms Demand in Arkansas, they give out gun locks, they're not saying, "Don't have them!" They're saying, "If you can't afford a gun lock we will give you one. Be safe." And they have remarkable success, even in states where the NRA is kind of strong, by hitting that kind of mom.

So that's another example, and then a third one, that's an idea I would love to see utilized more, is to push Democrats to really make an appeal to independents: "We're our own state. We don't let the national party set our agenda. We're independent and we make decisions for ourselves and what's best in New York may not be best here and that's OK." We often see that people who converting from R to D, that takes a really long time. Usually people will go to being an independent, or they split-ticket vote.

So, giving them permission to say, "Do what's best for your state, look at each office. Don't be beholden to a party," I think that could really appeal to some folks in certain states where Democrats are really underwater, like Alabama, Arkansas and Mississippi. In other words, say, "The Mississippi Democratic Party is something different, and we gotta address the problems in Mississippi," and to be Mississippi-centric.

They say politics is local, right? I think that could be a strategy for Democrats in those kinds of states. Because Republicans in those states really do attach themselves to the national agenda, and it leaves that lane open. So I would think "Go local, go local, go local. What are things that Mississippi needs?" Infrastructure, for example. We have places that don't have broadband.

I would like to see some of the Southern states get real state-specific focus in their races and in their candidates, all the way down the ballot. The advantage Republicans had when they started trying to flip the South is that the Southern voters they were trying to flip were starting to align with the national party. With the Democrats, it's the opposite. The only thing you can do is build from the bottom up, have Democrats running in every city council race, for every school board office. Because whoever that person is, that extra hundred people who show up because they actually know that person personally, sometimes those ballots go up.

So I think in the South they're doing a fantastic job of recruiting quality candidates. I would give them an "A" on that — just really picking great people. We just need more of them. It's a hard thing to do to step up to run when you know you might get 35% of the vote. But Republicans did that. They lost and lost and lost and lost in some places, until they won.

You've already spoken to the advantages and disadvantages of the grassroots organizing that's going on. Is there anything else you'd like to say about that?

One of the big advantages that Republicans had when they're flipping the south is that the issues they were pitching lined up with some institutions that already existed in the South, the white churches. So when you already have that network like that inside, it helps. When you don't, you've got to build them, and not just for election season. So where are your civic organizations? Where are your social media groups? Where are your PTOs? What is already existing , and what can be built on it?

I think in a lot of ways, some of that's what Moms Demand has done with moms' groups, but you have to find those things whether it's farmer coops or HBCUs or whatever and not just reinvent the wheel. There are some groups that are concerned about agriculture, concerned about climate, concerned about different things, those are perfect opportunities, kind of the way labor unions were outside the South — because of course we don't have them. But coronavirus showed us restaurant workers associations, all kinds of civic and volunteer groups that have helped at the local level, they can be reached politically too.

Your book shows that the Southern strategy transformed the GOP as well as the South, and as a result, transformed national politics as well. Is there a parallel potential to be found in the bottom-up organizing that's going on in the South today?

Oh, definitely! It's a little different in places like Wisconsin and Michigan, and so on. Because one election cycle of going one way or the other is different than what you're seeing in Texas. Democrats in the South were in power for so long in the 20th century, they got complacent in maintaining that infrastructure and keeping people excited about the party, and keeping a deep bench of candidates and getting young people involved in the party, and being a presence beyond election season. So when they lost power, they didn't know how to play offense. So I think it's pretty important for other states like Michigan and Wisconsin not to rest on the fact that it's almost always been Democratic. They could fall into that same trap.

If I was in charge of the Democratic Party, I would go, "We need a full autopsy, where are we killing it, where are we starting to see fewer contested primaries, fewer people coming in, all of that." Even when you're winning, or even when you rarely lose, you can't get complacent with it. The coronavirus just emphasized that. If Biden actually wins in Georgia, it's going to be because Stacey Abrams was prepared and was thinking all of this through and had people on the ground ready to help people to their polling places and all of that. That just takes a lot of investment, and I hope the Democratic Party keeps investing in the South.

Anything more you'd like to say about what did or didn't happen in the South?

I'm glad to see them fighting on every ballot. Count every ballot. Because that's what Republicans would do. If you get Southerners to show up and vote for a Democrat, they want to see that person fight for that vote. And the margins matter. You lose a race 45-55, that's one thing. You lose it 48-52, now you've got a lot of Democrats thinking they can do it next time: "I can close that gap!" It's thankless work when you keep fighting and losing and I think what Stacey Abrams and Beto O'Rourke did very well is tell their supporters, "We're not giving up."

So what's the most important question I didn't ask? And what's the answer?

What did Southern white women do? And I don't know the answer yet. Hillary Clinton won white women outside the South by four points, and lost them in the South by almost 30. With all this talk about suburban women — I'm not questioning it, but I always want to say, "Are you talking about white suburban women? And where?" Because so many national polls under-sample the South, and if those white suburban women in the South moved, that's a story. But I don't think they did. So I understand the criticism of white women and their vote, but knowing that it's potentially a regional problem is really important for our understanding of the national picture, because there are a lot of white women working hard for progressive issues outside the South. In fact, there's a majority.

And think about it: If they can flip Texas, it's not just six electoral votes. That fundamentally changes the game. Do people think that's going to be easy?

We're so close to changing everything.

We're so close to changing everything and that's when it gets the hardest, when you're right there. Because they will throw up every obstacle they can and that's exactly when you have to fight harder, and not give up. And that's what we're going to do.

Shares