In late July, a group of Kentucky gardeners and farmers marched through downtown Louisville, pushing wheelbarrows and demanding justice for Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old unarmed Black woman who was fatally shot by Louisville Metro Police Officers in March.

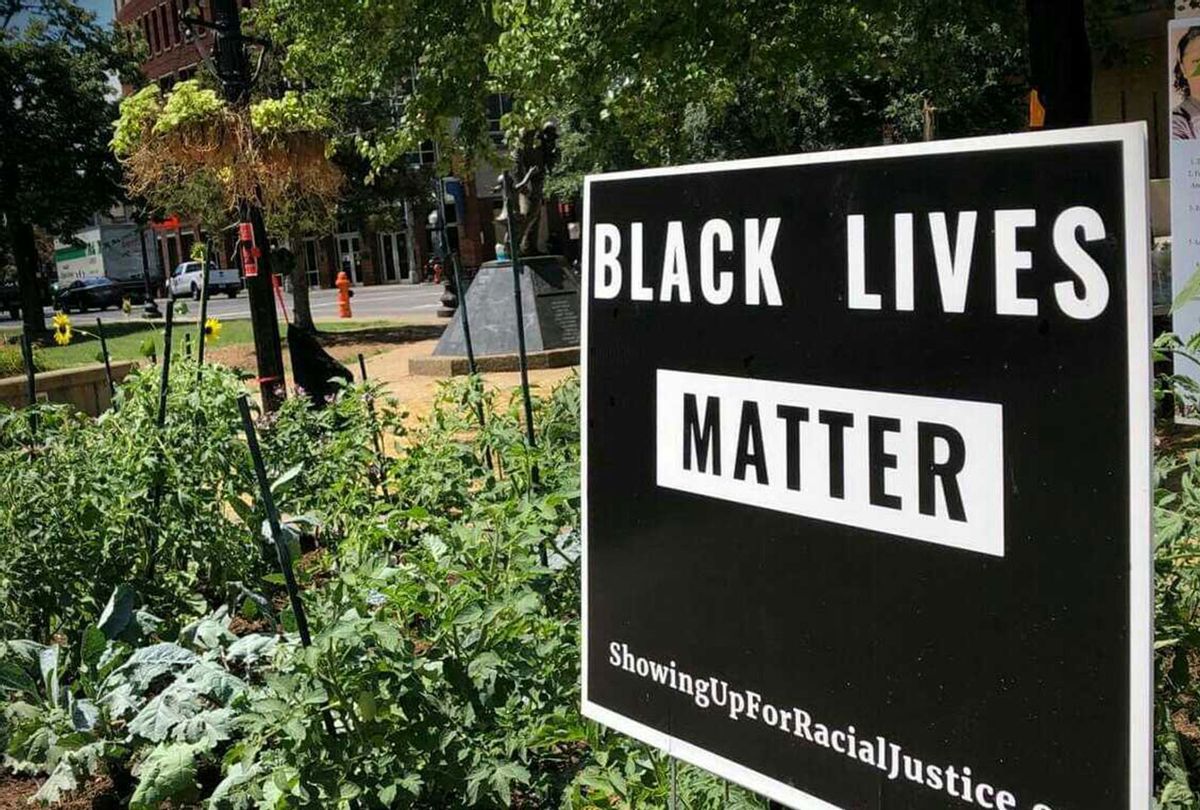

They started at a local farmer's market and moved 1-1/2 miles westward, towards Jefferson Square Park — now called Injustice Square, after serving as the nightly gathering place for protesters — where they had planted Breonna's Roots, an edible garden that was bursting with summer produce like ruby red tomatoes and peppers, deep purple eggplants and bunches of kale, dill, rosemary and parsley.

According to volunteer Jody Dahmer, the vegetables were harvested and transported a few miles further west to be distributed in Russell, one of Louisville's historically Black neighborhoods that is also one of the city's most barren food deserts. There are only two accessible major supermarkets to serve nearly 60,000 residents (and there's a longstanding rumor among food access advocates in the community that the nearest Kroger will eventually close permanently, after it shuttered sporadically amid protests, leaving only one option).

But now, the weather is snapping cold. Temperatures dip into the low 30s overnight, and soon, Injustice Square will be blanketed with morning frost, so the garden volunteers are having to pivot.

"With frost dates approaching, we are focusing on cole crops," Dahmer said, referring to a designation of cruciferous vegetables like broccoli and brussels sprouts that grow better in cooler temperatures. "But [we] also have garlic and onions planted between."

This isn't a unique conversation — all across the country, community garden leaders are having to adapt their plots for the winter or, in some cases, simply latch the garden gates behind them until early spring. But in food insecure neighborhoods, those decisions can have a community-wide impact on produce access, a sad reality that is particularly evident during the colder months.

"It becomes a real scarcity over winter," said Cordia Pugh, the founder of Hermitage Community Gardens in Chicago. "A real scarcity as we race through the winter, waiting for spring to come when we can get back in the gardens to get fresh produce."

Pugh spoke with Salon earlier this year about her community gardens, which are located in Englewood, where, according to municipal data, nearly 95% of the neighborhood's residents are non-Hispanic Black, and nearly 80% of that population lives with low or volatile access to fresh produce.

"This is not hobby gardening, this is food security for us," Pugh said at the time. "This is food insurance in the epicenter of a food desert. If we did not grow this fresh produce, we would not have fresh produce accessible to us. There is no accessible big box store in this community — or if we bought it through those venues, it would be from vendors that would quadruple the price."

Typically, Pugh works with garden volunteers over the spring and summer to preserve fresh produce for the colder months, but the pandemic lockdowns and social distancing recommendations drastically impacted that initiative. There is very little produce stockpiled, as a result, and Pugh said that she's currently in the midst of attempting to get fresh produce boxes to her garden members.

"I'm speaking out of my own desperation this year, because I'm really scrambling now to get the resources in place for fresh produce food distribution over the course of November through April of next year," Pugh said. "Especially because some of our members don't have access — financially or otherwise — to those big box stores."

And even if they can get to the store, Pugh said, there's no guarantee that the quality of the produce available will be the same as in stores in more affluent or mixed-race areas.

This is a well-documented phenomenon. In 2010, The Food Trust, a Philadelphia-based food access nonprofit, and the Oakland-based PolicyLink published "The Grocery Gap," a comprehensive paper that detailed how, in hundreds of lower-income communities of color, access to healthier foods like high-quality produce, high-fiber bread and low-fat milk was compromised.

In Louisville, Shauntrice Martin has taken the last several months to examine these disparities, focusing specifically on the city's food deserts, like Russell. Martin is the founder and director of #FeedTheWest, a community food justice initiative that advocates for a Black-owned, fresh food source for residents.

She published her findings under the title, "The Bok Choy Project," wherein she compared five Krogers across five different zip codes, assessing four characteristics: the number of organic produce options available, the presence of police officers, the Black population of said zip code, and the availability of bok choy.

According to Martin, she chose bok choy as a stand-in for "premium produce" because it was an item that she only saw on shelves once she moved out of West Louisville to Maryland when she was in her 20s. Now that she's back, she definitely sees discrepancies in selection and quality between the supermarkets in the zip code with 11% Black population — 11 organic produce options — compared to the one with 92%, which had only three organic options.

"When you walk into that store, there is an 'organic section,'" Martin said. "But it usually only has pears and apples. The rest of it is conventional produce. It's wilted, some of it is rotten or expired on the shelf."

These are the options that are available, Martin and Pugh said, for food insecure communities, which statistically tend to be lower-income communities of color. And while community gardens like Hermitage Community Gardens and Breonna's Roots serve as a stopgap in warmer months, they aren't a replacement for equitable food access and distribution systems.

In Toronto, the food access nonprofit FoodShare spends a lot of time thinking about what food security actually means and what food sovereignty would look like in Northern climates that experience winter. According to Natalie Boustead, the organization's community gardens leader, a lot of our current eating habits are reliant on expensive greenhouse production and imported items to maintain a level of consistency in our diets throughout the year.

"Which, if we were actually eating locally, seasonally [and] within a framework of true self-reliance here in Northern climates, would not be possible," Boustead said. "If we were to shift our cultural expectations around eating seasonally to involve only eating dried fruits, and fermented, salted and sugared foods from summer harvest . . . we may have a shot at actual food sovereignty and self-sufficiency."

Not to mention, she said, there would need to be a complete overhaul of North America's racist food distribution system.

"Until all of that begins to shift, there are very few deeply meaningful ways that those experiencing food insecurity in an urban setting can do to lessen their systematically entrenched relationship to an unfair food system, especially in winter months," she said.

Shares