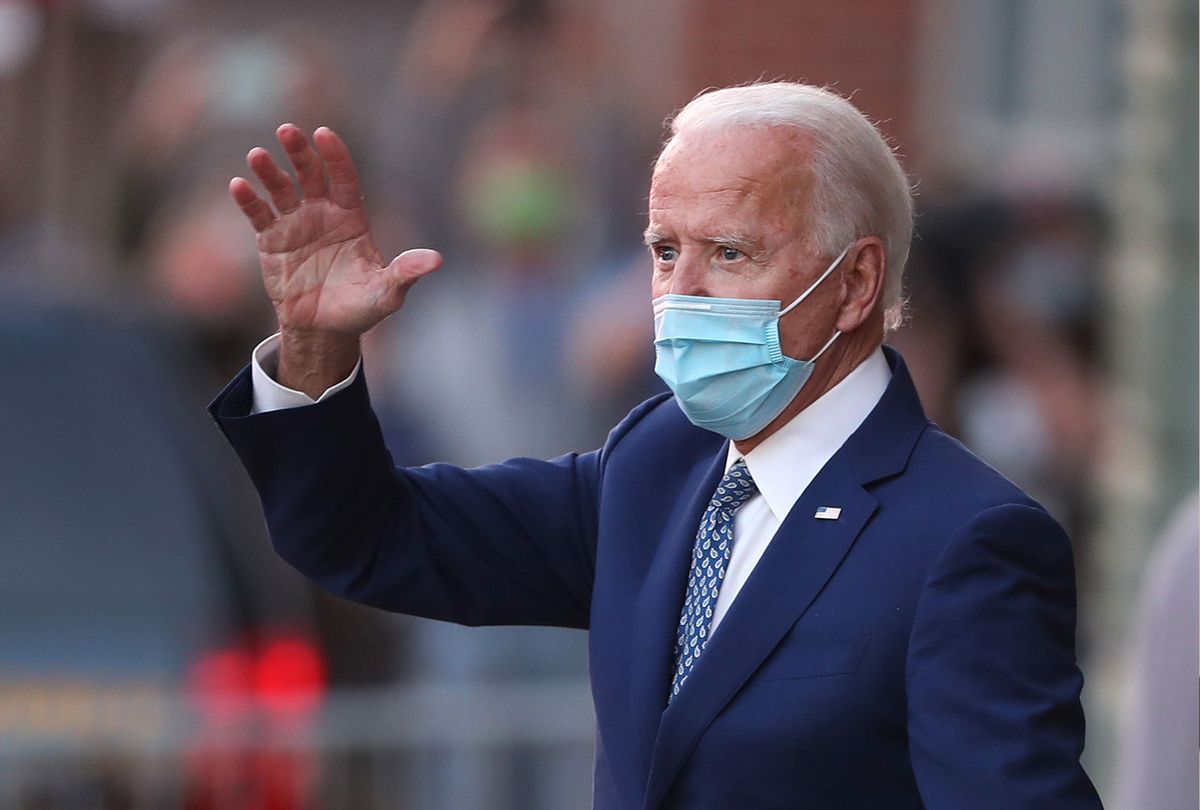

When president-elect Joe Biden announced in his victory speech that he was going to immediately name a COVID-19 response task force, and created an "action blueprint" to hit the ground running on January 20, it was refreshingly innovative — a coherent, real-world approach to a devastating crisis. But what gave the incoming administration an even more groundbreaking tone was Biden's vow to create a plan "built on bedrock science… constructed out of compassion, empathy, and concern."

Science and empathy, together at last. Whew.

As anyone who has been to a doctor in America can attest, medicine and humanity generally run on separate tracks — if you're lucky enough to get any of the latter at all. And somehow, that's been considered acceptable. It shouldn't be. I've spent the past two years studying narrative medicine and medical humanities, interdisciplinary approaches to healthcare that are challenging those outdated preconceptions. Sickness doesn't take place in a vacuum. Cures can't either.

A year ago, I was speaking before a large scientific organization and talked about the need for active listening and thoughtfulness in patient care. "That's what nurses are for," one male attendee shot back. I don't know why I was shocked. His assumption is a common one, even among those of us outside the healthcare professions.

"Wouldn't you rather have the best surgeon, instead of one who was just nice to you?" a fellow journalist asked me recently, as if "the best" is an objective judgment independent of mitigating factors, and that "nice" is a red flag of incompetence. The writer's attitude reminded me how, a decade ago, I walked away from a clinician who was rude and insensitive to me during a consultation. The doctor's track record with people he's treated looks impressive to this day, but there's no way of factoring in how many other patients like me may have left and found other other practices, or abandoned treatment entirely, because they didn't feel confident in his level of sincere care.

Science is precise, but data only tells part of any story. If, for example, we look solely at press releases for updates on COVID-19 vaccines, it would not be easy to see how disproportionately clinical trials thus far have underrepresented black patients — even though they're five times likelier to be hospitalized with COVID and twice as likely to die from it. Across a variety of challenging public health crises, including cancer, nonwhite patients typically make up fewer than ten percent of clinical trial participants.

That's not a failure of science. It's one of trust and communication. It's rooted in grotesque abuses like the Tuskegee experiments, but often perpetuated by a lack of focused recruitment and engagement. In all aspects of medicine, but especially in innovation, respect for and curiosity about human beings has got to be baked in to the system.

At the research level, the virus or the disease is the primary focus of attention, but potential patients themselves are too often mere abstractions. No wonder, then, that when treatments finally enter the patient world, the patient can often feel like an afterthought. Clinicians babble out directives using complicated terminology. They rush through visits because they're overbooked and overtaxed. Materials meant to clarify our questions only leave us with more. The informed consent paperwork for my immunotherapy clinical trial, for example, was 27 pages chock-full of medical terms I didn't understand, communicated in legal jargon and handed to me at one of the most devastating, distracting moments of my life. It was a document that seemed entirely untethered to the real person who had to read it. I didn't feel informed at all. How could I have truly consented?

And this is where the humanities — those often neglected, much derided studies our parents begged us not to major in — actually have profound value. As a feature in The Week condensed it in 2018, medical students who are educated in the liberal arts not only gain a much-needed "social and cultural context" to apply healthcare in the real world, they develop a deeper aptitude for empathy, as well as a broadened base of skills like spatial reasoning. Whether you're in a lab working for a biotech company or a surgeon or a family practitioner, those are all necessary for competent, comprehensive medicine and research. Biden's newly announced COVID-19 response team likely understands this. It's certainly telling that one of its members is Atul Gawande, who describes his skills as "writing/surgery/research" and has carved out a bestselling career as an interpreter of medicine to the masses.

In clinical trials, participants have to be active reporters of their own experiences and symptoms. They have to have a strong motivation to enroll and to stay enrolled. That only happens when the studies are designed by people who see patients as humans instead of (ugh) "human subjects." Reciprocal, respectful relationships are critical for the collection of meaningful data, and they're essential for assuring that fewer trials fail before promising treatments make it to market. It's just that simple.

Good science relies heavily on good people. It needs people with strong critical and abstract reasoning, who see their work in broader terms than endpoints. These things are not afterthoughts; they aren't just what are insultingly referred to as "soft skills." As my doctor, whose lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering bears his name, puts it, "I don't treat cancer. I treat people." Whatever comes next for all of us, we now have an incoming president who understands that humanity, compassion and empathy belong right at the side of bedrock science. And that curing a virus will mean listening to people.

Shares