It seems like performative activism is here to stay. America seems just fine with white people, corporations and other organizations simply saying "Black Lives Matter" and doing nothing more. In fact, in the months since I first said I was tired of performative bullshit, it's gotten worse. The COVID-19 pandemic is still raging, even though Americans have decided it's over. Jared Kushner thinks that Black people need to want to be successful to survive – and the presidential election has shown us that America's inherent racism is alive and well. We have a white supremacist majority in the Supreme Court that threatens to dismantle what's left of democracy, and a new justice with a highly-questionable résumé that a Black woman would be sent home immediately for even producing. And the response? Though it was nice to have people from all walks of life join us at protests, white folks still appear to be marching themselves into the abyss months later.

A few of us thought this moment might be different because we were hanging onto a thread of hope that white people might actually get themselves together and make real change. But alas, here we are … I'm still tired.

Protestors across the country have been taking down statues of slave owners and oppressors. But now, people have also decided it's a great idea to monument us in addition to making empty statements about our lives mattering. The response to this moment cannot just be erecting more statues and producing artifacts for Black lives that should have never been lost in the first place.

Commissioners in Miami-Dade County are renaming the street outside of Travyon Martin's high school after him. Though it is a nice gesture, that's exactly the kind of performative action that makes people in power feel good, but doesn't actually address systemic racism and injustice. Earlier this fall, the Minneapolis City Council decided to name a part of the street where the horrific murder of George Floyd happened after him — the same City Council that called for defunding the police department immediately after his murder, but has now backed away from those calls to action. And remember the grand gesture of unveiling Black Lives Matter Plaza in the racist president's backyard? The street may have a new name, but many people experiencing homelessness still occupy that area thanks to systemic racism, injustice and lack of opportunities in the nation's capital. And we've all seen the many magazine covers of Breonna Taylor and the jewelry that lets you parade the names of Black lives lost on your neck, egregiously commodifying access to our lives.

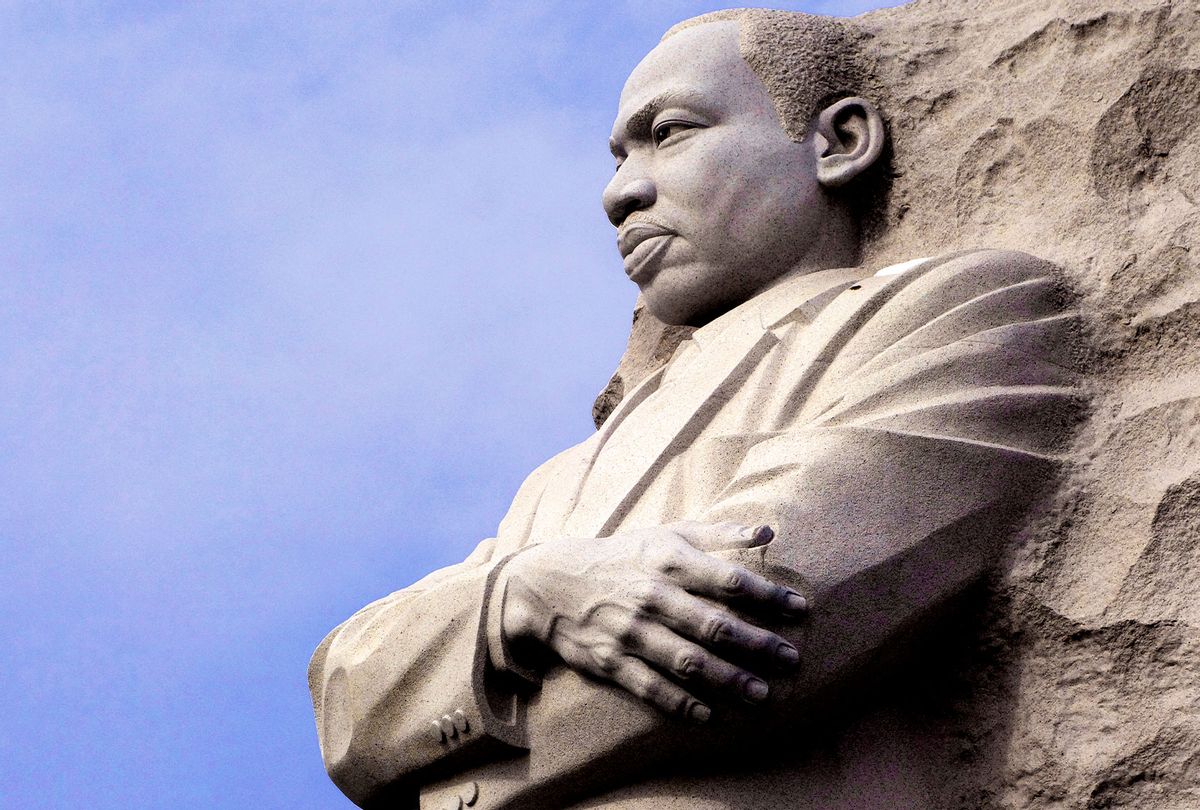

It is easy to rename a street, to hold a ceremony, to claim solidarity, to perform for press and social media. It is harder — much harder — to actually implement and rethink policies that help and not harm Black people by pushing for institutional changes that bring about real justice. Perhaps among the greatest historic performative actions was the naming of streets after Martin Luther King. Over 900 streets in the U.S. are named after MLK, and the majority of them are home to liquor stores, boarded up buildings, and represent lines of segregation where white people dare not visit and refuse to invest in out of fear and racism — a slap in the face to Dr. King's legacy and the urgency of preserving, restoring and progressing Black communities.

America is built on a lot of ceremonial nonsense — including reenactments of the Civil War, plantation tours where we pretend enslaved people were happily living with their owners and ignorant weddings that accompany them, and the Pledge of Allegiance — and white supremacists love their statues and monuments to slavery (e.g. the Confederate flag). But the change we seek isn't to turn the Black life you took into monuments for Black Lives Matter. And the excuse for not doing more than ceremonial performances can't be "we don't know what to do" or "we're still learning." Racism didn't just arrive in 2020.

The change we seek is that you actually do the hard work to make Black lives matter. I mean the hard, often uncomfortable and sometimes confrontational but necessary intersectional change that forces people in power to dismantle their own biases to make Black people matter, including Black women's lives and Black LGBTQ+ lives.

That means that officials and politicians who shout "Black Lives Matter" must also invest in our communities by supporting and embracing Black-owned businesses, providing access to capital, and allowing entrepreneurs to flourish. It means that cops don't need to bother with "serve and protect," but rather respect us and maybe actually live on MLK Boulevard with us. It means limiting the power of police unions and not sending cops to our homes, schools and neighborhoods, when professionals who deal with mental illness and other social services might be better suited. It means that you employ us before you incarcerate us — and restore voting rights post-incarceration. It means restorative justice isn't solely about the victim. It means that suicide and homelessness among Black LGBTQ+ youth should matter, and that you can't just shout you care, but legislate your way to caring by creating inclusive policies and laws. It means that Black women are no longer the exception, but the rule when it comes to our leadership, talents, skills and wisdom — and that it shouldn't take an absurd amount of years to even get laws on the books that prevent discrimination based on our hair. It means you stop preaching at us to vote without expecting accountability and making room for our protests. But mostly, it means that officials and politicians must know when to step aside, let us lead, and stop treating us like pawns on a chessboard that can be moved around to win praise and allow for more performances.

My father was George L. Winfield, the first Black Director of Public Works (DPW) in Baltimore City. He was the best dad. I am undeniably my father's daughter, and I was fortunate to have him in my life until he passed away suddenly from a stroke when I was 23 years old — taken far too soon from the disproportionate effects of high blood pressure on Black people. He was a man of integrity, dignity and respect who literally gave and sacrificed his life for the city he loved — dying in office in 2007, having never been able to realize and enjoy the retirement he and my mom deserved and earned. He was a Vietnam veteran, a civil engineer who later won Black Engineer of the Year in 1989, and a Black man from the South who worked his way up to success despite the odds against him, having once been a janitor to take care of his family.

When I was in grad school, I bought my first car. I will never forget driving home to show it to my dad. I was so proud that he didn't have to sacrifice for it, because he had done so much for me and my brothers. I had figured out how to hardwire my radio and plug my iPod into it so I could jam out in the car. We drove around the neighborhood so I could show off my skills, and I vividly remember him saying, "You did that?!" He was impressed, and I knew it. College students run into tough times, and there was one month when I couldn't pay my car note. I begrudgingly gathered up the courage to ask Dad to help, with the promise that I'd pay him back. A few weeks later, I remember driving back home and feeling so good that I had saved up the money to pay Dad back. I got to the house and gave him the check proudly, thrilled I made good on my word.

He never cashed that check. I remember clearing out the house so my mom could move in the years after he passed away, finding the check, and having an entire breakdown — not only because I missed my dad, but I knew what our city had lost, too. He was that great.

After my father passed, Baltimore City officials chose to name a building after him, which was a lovely gesture. But my dad would've wanted equality and justice — more support, better benefits and pay for the mostly Black, Brown, justice-impacted, financially uncertain workers he managed who picked up trash and recycling, dealt with numerous complaints from residents, fixed potholes, managed weather emergencies, along with the other jobs they toiled away at daily.

That building won't bring him back to us, nor will it bring about justice for the workers and the city he loved. But today, some Baltimore City Council members are asking for better pay and support for those DPW workers. Achieving that would honor Dad more than any building ever could. A street named in his memory won't bring Trayvon back or end police murders of Black people, but there are lots of people fighting to change the police state in this country, including in Miami. Those in power should listen and act. Wearing an absurd and offensive "The Breonna" necklace might make you think you're stylish and on trend, but it absolutely will not bring Breonna Taylor and her family justice.

I now want to know what we do past this "moment of national reckoning," because we are seeing white folks already going back to living their privileged lives, never having to think about or act on racism because they don't value our lives enough or experience it. Additionally, recent polling shows that when protestors are identified as Black, support drops. And when white women start to have real talk with the 55%, let me know. Your marches are full of empty promises and until you take action that dignifies and respects Black women, I have no choice but to ignore you.

I don't want your statues, ceremonies, building and street names, martyr magazine covers, billboards, your Black Lives Matter signs in your yards and windows, or whatever other ceremonial relic you try to placate us with right now.

I just want you to stop killing us — and killing us again with ceremonial bullshit — and make our lives better while we're living.

Shares