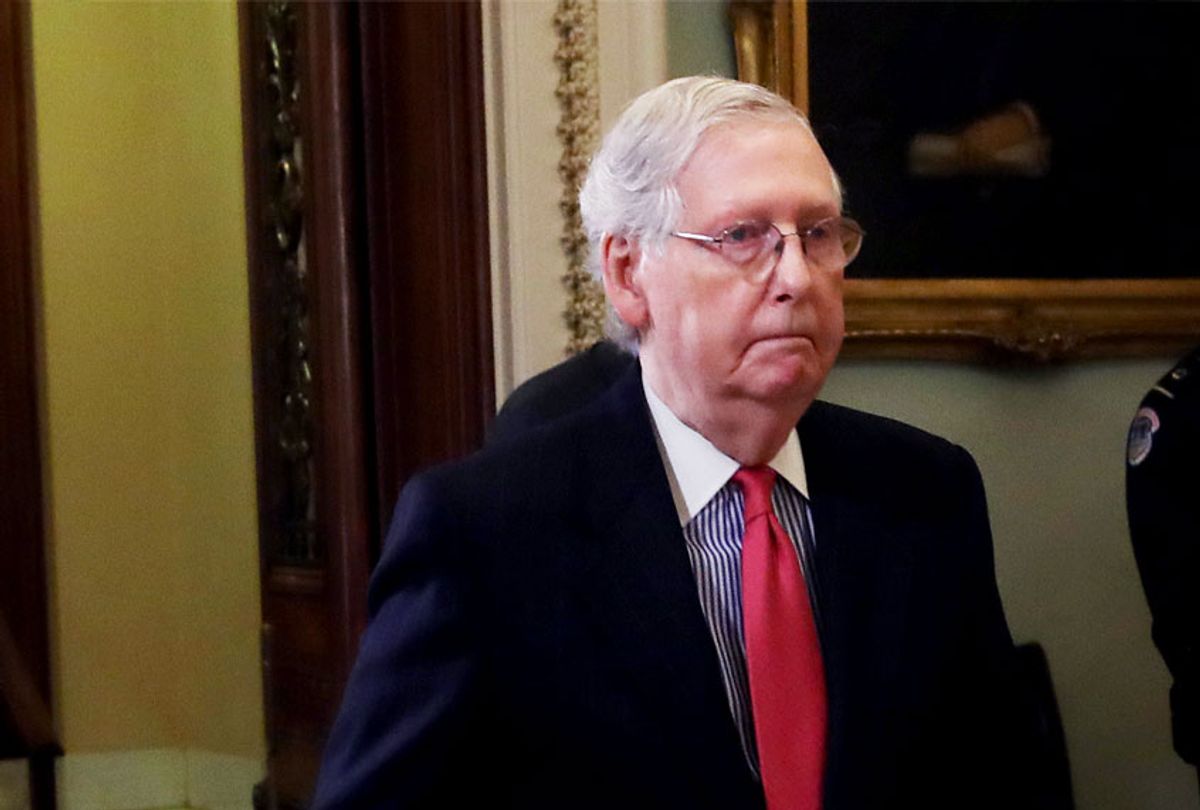

The next coronavirus stimulus bill needs to be at least four times larger than Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's (R-Ky.) $500 billion proposal, economists told Salon.

Congress remains deadlocked on a bill after McConnell repeatedly rejected the $3.4 trillion HEROES Act passed by the House back in May, and the $2.2 trillion compromise offer House Democrats approved last month.

McConnell said this week that a bill "dramatically larger" than his $500 billion proposal is "not a place I think we're willing to go." Yet economists say the country needs at least $2 trillion to help the economy recover back to where it was before the pandemic, just as the US enters the worst wave of the coronavirus pandemic yet.

McConnell's delays threaten to worsen the issues that the stimulus bill is supposed to relieve.

"The delay in providing the stimulus almost surely will increase the amount of money necessary to restore the economy," Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel-prize winning economist and Columbia University professor, told Salon. "Balance sheets of households and firms get eroded and firms go bankrupt. Digging yourself out of a deep hole is much more expensive than preventing a decline into a deep hole — another instance in which the aphorism an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure is applicable."

The rise in coronavirus infections in recent weeks has compounded the problem. The number of new confirmed cases in the country topped 150,000 for the first time on Thursday, though the true number is likely far higher since positivity rates in certain states suggest testing is missing a massive number of cases.

The issue should not be a matter of cost but an issue of need, argued Michael Graetz, a former senior Treasury Department official and co-author of "The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and How to Fight It."

Small businesses are closing around the country and, despite many re-openings, there are still more people unemployed than at any point since the Great Depression. "So we need to do what we did in the CARES Act," said Graetz, who is now a professor at Columbia. That includes additional loans and grants to keep businesses open, enough money to provide at least $300 to $400 per week in federal unemployment benefits, funding to help struggling hospitals, another round of $1,200 checks to help people pay rent, and funding to help state and local governments that have "run out of money."

All of those measures add up to close to $2 trillion, he estimated.

"You're talking about serious problems that need to be addressed," Graetz said. "It's like going shopping for your children when school starts. You don't ask how much am I going to spend, you ask what do they need."

Graetz argued that the government must get the economy through the next six months until there is an "effective vaccine" that is widely distributed.

That view is shared by a large number of economists. The left-leaning Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that it would take at least $2 trillion to provide $400-per-week unemployment benefits, food and housing aid, and state and local government aid without taking into account funds for virus testing and other pandemic-related efforts. Other economists estimate it may take $3 trillion to $4 trillion to help the economy recover.

Josh Bivens, the director of research at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, argued that the path to recovery would take years and far more funding than is being discussed for the next round of relief.

Restoring the unemployment rate to the 3.5% it was before the pandemic would require about $800 billion per year in stimulus funding totaling between $1.5 trillion and $2 trillion if it was for "very effective" stimulus measures like federal unemployment benefits and state and local aid, he told Salon.

"Then, however, we can't just turn it off like a spigot, because that would be a big fiscal cliff," he said, adding that it would take another $400 billion per year over several years to "slowly manage the transition of demand being stimulus-led from private-sector led."

Aiming toward an even lower unemployment rate would require at least another $100 billion per year over several years, he estimated.

A major impasse in negotiations has been over the size of the unemployment benefits. Democrats have been steadfast in their demand to keep the $600-per-week federal boost that was included in the CARES Act while Republicans are pushing for a figure closer to $300 to $400 per week. Republicans have argued that the higher number is a disincentive to workers to return to their jobs even though studies have repeatedly found that the generous federal boost had no impact on the labor market. EPI's research estimated over the summer that reducing the benefits to $400 would shrink the economy and cost millions of jobs.

But with so many months since the benefits expired, Graetz said Democrats should cave and agree to a lower figure in the interest of getting the money out sooner to the people who need it.

"I think they should agree to do less in order to get the money out the door. Every week that passes that is $400 less that people who are unemployed have," he said. "Their households are at stake. If you can't get $600, you have to accept $400. The American democratic system is built on compromise."

Another impasse has been over aid to cash-strapped cities and states. Tax revenue for local governments dried up amid the shutdowns and the damage is only expected to get worse as the country enters what is expected to be a devastating winter. While Democrats have sought $1 trillion for aid to city and state governments, McConnell has deemed the proposal a "blue state bailout." He suggested earlier this year that the country should "let states go bankrupt," which is illegal, and pushed to exclude any new money for states in his September proposal.

Graetz said that failing to save struggling cities and states would "absolutely" worsen the problem by resulting in more layoffs.

"We're looking at six more months at least of state and local governments not getting the revenues that they need to function," he said. "I don't understand why Congress, which has the ability to provide the money, has decided that it would like to see this as an occasion for layoffs of public workers. There's this myth that state and local governments can balance their budgets if they just cut out fraud, waste and abuse. But instead, they're going to cut out teachers, policemen and firemen."

Graetz pointed out that while mostly Democratic-led states were hit hardest in the spring, the areas where hospitals are now filling up are in "Republican states."

"Republicans governors need money as much as the Democratic governors do," he said. "This is not a red state-blue state divide when it comes to addressing this problem."

Graetz said he shares Republican concerns over the long-term impact on the debt and deficit but "this is an emergency and it needs to be addressed."

"The human costs are just enormous," he said. "I think this is an emergency. The government needs to respond to emergencies. It responded to 9/11. The scope of this is far greater than the damage of 9/11. And it needs to respond. We spent $10 trillion fighting wars in the Middle East in response to 9/11. We need to spend what we need to spend now."

Bivens urged lawmakers to consider other long-term implications of coronavirus relief measures.

"These cost-estimates are basically things laser-focused on normalizing unemployment," he said. "We need a lot more than that to have a generally decent society that provides broad-based economic security."

Those measures include "deeper social insurance," including working to "delink health insurance and jobs," he said, as well as investments in early childhood care and carework, and regulations and rules that "empower workers to get a bigger piece of the pie."

"The pre-Covid low unemployment rate basically disguised just how rotted our economy had become in its potential to deliver genuine security for all," he added.

But it's impossible to predict the full scope of the relief measures needed because of the uncontrolled spread of the virus across the country that shows no sign of slowing.

"Obviously the big danger to everything in next couple of months is the virus," Bivens said, "and we cannot spend enough money in efforts to contain that."

Shares