Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who teaches medicine at Stanford University and is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economics Research, has become popular in conservative circles for challenging the extent of the coronavirus' deadliness and the need for widespread lockdowns. Yet the advice issued in his popular articles are far outside the scientific mainstream from accepted public health policy, and scientists say that they may even be "dangerous."

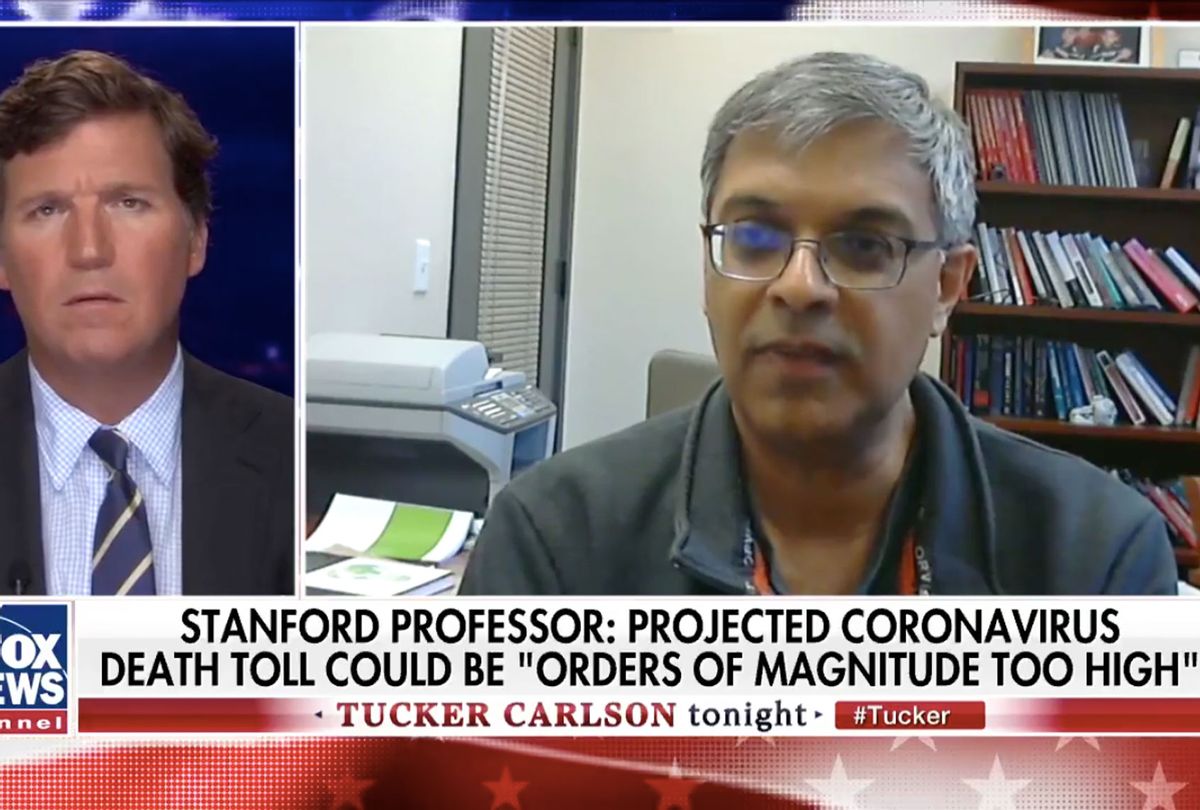

There was his interview last month with Fox News host Laura Ingraham, where he described a lockdown in Victoria and Melbourne, Australia as "nothing short of draconian." In April he told a different Fox News host, Tucker Carlson, that the actual death rate from coronavirus infections is "likely orders of magnitude lower than the initial estimates," adding that "per case, I don't think it's as deadly as people thought" and that "the World Health Organization put an estimate out that was, I think, initially 3.4 percent. It's very unlikely it is anywhere near that. It's much likely, much closer to the death rate that you see from the flu per case."

Bhattacharya has also appeared on Spectator TV — an outlet considered the voice of the UK's Conservative Party — saying, "What we need are new ideas for containing the damage of the virus, rather than trying to contain the general spread, which has been proved to be a poor strategy." Carly Ortiz-Lytle, a writer for the right-leaning DC Examiner, tweeted this last week about one of his interviews: "Whether you disagree or agree with lockdowns, this is worth a watch. Dr Jay Bhattacharya explains creative alternatives to lockdown."

Who is Bhattacharya, and what does he believe?

Bhattacharya codified his views in a document called the Great Barrington Declaration, which he co-signed with Harvard University's Dr. Martin Kulldorff and Oxford University's Dr. Sunetra Gupta. A manifesto of sorts, it claims that policymakers should implement a system called "Focused Protection" rather than major nationwide lockdowns. This would entail making sure that groups deemed most vulnerable to COVID-19, such as the elderly in nursing homes, receive extra care and protection, while at the same time easing lockdown policies to protect the physical and mental health of the rest of the population.

Bhattacharya and his co-authors also argue that herd immunity is attainable even without a vaccine and that it therefore makes sense from a public health perspective to allow people who are not vulnerable to "resume life as normal." Yet recent studies suggest widespread herd immunity may not even be possible for COVID-19 given that infection appears to only confer transient immunity; even if herd immunity is possible it would partially rely on the widespread distribution of an effective vaccine.

In a panel presentation delivered last month at Hillsdale College Free Market Forum, Bhattacharya also claimed that the COVID-19 fatality rate is "much closer to 0.2 or 0.3 percent" than the accepted figure of 2-3 percent or higher, if you base the figure on seroprevalence — or, how many people have evidence in their bloodstream of having had COVID-19. He also reiterated that the disease is much more dangerous for the elderly and infirm than for children.

From a political standpoint, it is clear why these beliefs resonate with conservatives: they affirm the conspiratorial belief that the pandemic is being blown out of proportion. While Bhattacharya doesn't claim to believe in any larger political agenda here, it is easy to see how someone who believes the pandemic has a conspiracy attached to it might latch onto Bhattacharya's ideas as evidence of such a thing. As MedPage Today pointed out, the Great Barrington Declaration was sponsored by the libertarian, free-market think tank the American Institute for Economic Research, and many of the 8,000 signatures included on the document were later determined to be fake.

What does the science say?

The science does not support Bhattacharya's views, and multiple scientists Salon interviewed disagreed with the Great Barrington Hypothesis' assertions.

"I think 'case/fatality' is a confusing issue," Dr. Alfred Sommer, dean emeritus and professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Salon by email. "The rates vary by disease and they way they are defined. 'Case' fatality is sometimes meant to mean the death rate among cases (e.g. people with some physical evidence of the disease – they are "sick"); in other instances it is more loosely the rate of death amongst all those who are infected. So what the 'true' rate is depends upon how people are defining and counting."

He added, "When we compare this with past pandemics, the latter were generally basing their rates on deaths among those who were ill; there weren't widespread sero-surveys for the rate of infection. Nor do we have such data for this pandemic – if you want to really know the fatality rate among all those infected, at a minimum you need to check the number infected in a random sample of the population – as far as I know that hasn't been done anywhere (and certainly has not be done in the U.S.)"

Sommer is not alone in finding flaws in Bhattacharya's reasoning. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told The Washington Post last month that "anybody who knows anything about epidemiology will tell you that [Bhattacharya's co-authored paper] is nonsense and very dangerous, because … you will have killed a lot of people that would have been avoidable."

National Institutes of Health Director Dr. Francis Collins, who is most famous for helping to decode the human genome, likewise denounced the Great Barrington Declaration as "dangerous."

In a memorandum released in the respected scientific journal The Lancet last month, a group of more than 30 scientists denounced the "so-called herd immunity approach, which suggests allowing a large uncontrolled outbreak in the low-risk population while protecting the vulnerable" as "a dangerous fallacy unsupported by scientific evidence." They concluded that "such a strategy would not end the COVID-19 pandemic but result in recurrent epidemics, as was the case with numerous infectious diseases before the advent of vaccination. It would also place an unacceptable burden on the economy and health-care workers, many of whom have died from COVID-19 or experienced trauma as a result of having to practise disaster medicine."

Salon also reached out to Dr. Russell Medford, Chairman of the Center for Global Health Innovation and Global Health Crisis Coordination Center.

"The full consequences of Dr. Bhattacharya's strategy have not been addressed in his report," Medford wrote to Salon. "For example, while age is a strong determinant for risk of serious illness and death from COVID-19, it is not the only determinant. Up to 40% of the US population has one or more underlying medical conditions (such heart disease, obesity, hypertension) that confers increased risk of serious consequences of COVID infection. How we identify and segregate such a large proportion of the population is not trivial and may not be achievable."

He added, "Another example is that by defining a vulnerable population based exclusively on death rates, the report does not address the early, but growing, body of evidence that COVID-19 can potentially result in significant prolonged illness and persistent symptoms, affecting the heart, lung and brain, even in young adults and persons with no underlying medical conditions who were not hospitalized."

Bhattacharya is affiliated with the Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank at the Stanford University campus that has produced a number of pundits who deny scientific facts about COVID-19. As physician Dr. Ashish K. Jha tweeted last week, Bhattacharya and Trump adviser Dr. Scott Atlas "shaped Trump's plan on COVID. Let infections spike while 'protecting the vulnerable' with one caveat. There was no effort to protect the vulnerable. The effect? Deaths spiking across the nation."

Salon reached out to Dr. Bhattacharya for comment; in an email, Bhattacharya reiterated the assertions in the Great Barrington Declaration. He argued that it "lists various sets of people harmed by lockdown, including the vulnerable urban poor and older people forced to live in multigenerational homes as a consequence of lockdown. There is also an enormous body of evidence that documents the psychological and health harms induced by lockdown, with the poor in every poor country on earth hit the hardest." He also disagreed with the individual points made by some of the experts interviewed by Salon.

Shares