Much has already been written about “Happiest Season,” Clea Duvall‘s Hulu romantic comedy that stars Kristen Stewart as Abby, a graduate student who plans on proposing to her girlfriend, Harper (Mackenzie Davis), on their Christmas trip to meet her conservative parents, the Caldwells.

The catch? Harper never came out to her parents, Ted (Victor Garber) and Tipper (Mary Steenburgen), and asks Abby to spend the next five days pretending to be her straight, orphaned roommate who simply tagged along because she had nowhere else to go.

Harper’s family is . . . absolutely awful. Ted is a deeply conservative politician running for mayor, Tipper is obsessed with family legacy and image, and Sloane, Harper’s older sister (Alison Brie), is icy and competitive. Two minutes into meeting them, it’s clear that things aren’t going to go well for Abby — especially once it becomes clear that Harper becomes a worse person when around them.

“Worse how?” you might ask.

Well, for starters, after pushing Abby back in the closet, Harper ditches her to go drink with her ex-boyfriend until two in the morning, then proceeds to call Abby “suffocating” when called on it. It’s a pattern of really bad behavior for which she never really atones.

It’s an often-infuriating 102 minutes of holiday shenanigans and gaslighting, that left many viewers wondering why Abby didn’t just run off with Riley (Aubrey Plaza), Harper’s stylish and empathetic secret ex-girlfriend (whom, it should be noted, was outed by Harper when the two were in high school), or just go home to her best friend, John, a lovably acerbic book publisher played by Dan Levy.

Despite its imperfections, the movie has enough good going on that it’s worth a watch: it’s the first studio-produced holiday rom-com centered on LGBT characters; Levy’s and Plaza’s performances are pristine; Kirsten Stewart’s blazer and undone tie situation is enviable; and then there’s Jane.

Jane (played by “Happiest Season” writer Mary Holland), is Harper’s other sister. Unlike the rest of her family, she’s bright, bubbly and, as press materials put it, “wacky.” She also busts the screenwriting paradigms that typically surround quirky women characters.

“Jane really just came to life, in me, in a way that was so fun,” Holland told Collider. “In writing Jane, we knew that we wanted her to be this joyful character and this person who just really has such a deep level of self-acceptance.”

Jane’s level of self-acceptance is born from a position as the family black sheep. As Tipper puts it, “We gave up on her when she wouldn’t stop biting in preschool.” Her sisters have — or, in Sloane’s case, had — standard, “Dad-approved” jobs as a newspaper reporter and attorney; Jane has been working on world-building for her first fantasy novel for a decade. They quietly walk into rooms, she has an enthusiastic, Kramer-esque slide through open doors. They wear neutral, off-the-rack Banana Republic dresses, while Jane spends most of the movie sporting bright knits, chunky barrettes and florals that pop. (Tipper has also apparently banned her from wearing future outfits that “strobe.”)

While people in the Caldwell’s uptight Pennsylvania hometown might refer to Harper and Sloane as “driven” or “ambitious,” Jane is the kind of woman about whom those same neighbors would lower their voices, hesitate for a moment, before finally deciding on, “Well, she’s just quirky.”

Here’s the thing about quirky women: in film and television, they are often written in one of two ways, as either punchlines or, perhaps more often, sex objects.

Quirky women make for a tidy foil for more straightlaced or average characters, especially in the sitcom or cable television format. There’s Phoebe Buffay from “Friends,” Amy Farrah Fowler and Bernadette Rostenkowski-Wolowitz from “Big Bang Theory,” and Penelope Grace Garcia from “Criminal Minds.” Sometimes this results in characters who are endearing, if a little flat, because their peculiarities exist solely to serve as narrative fodder — but not always.

Think about Melissa McCarthy’s character, Megan, from the 2011 film “Bridesmaids.” She, like Jane, had an undeniable level of self-acceptance, an almost macho swagger, in this case. “I love those no-bulls**t women with close-cropped hair that you’ll see together and think, ‘Is that her partner?'” McCarthy told GQ after the film’s debut. “Then they talk about their husbands and six kids. I just love anybody who’s that comfortable in her own skin.”

While the entire “Bridesmaids” ensemble is stacked with comedic talent — Kristen Wiig, Maya Rudolph, Wendi McLendon-Covey, Ellie Kemper, Rebel Wilson — McCarthy’s role is distinct. It hinges on her eccentricity, which is evident in the dichotomy between her voracious sexual appetite and her gym teacher wardrobe ( SAS Comfort sandals, included!) and in her willingness to deliver lines like, “I’m life, Annie, and I’m biting you in the ass,” before going on to physically bite Wiig.

Her life is presented as a stream of peculiar circumstances: she fell off a cruise ship, pinballing into railings and decks, before being saved by a telepathic dolphin; she has mysterious financial resources; she steals nine puppies from a bridal party and later in the film waltzes into Annie’s mom’s living room with all of them pulling on their leashes.

There’s a kind of shamelessness to the character that is both endearing and strangely aspirational, likely due to the fact that this was a film largely guided by the female gaze; “Bridesmaids” was written by Wiig and Annie Mumolo.

What happens when quirky women are written from the male point of view, you may ask? Well, that’s when we sometimes lapse into the eccentric sexual interest who only exists to teach a man about himself, known now in pop culture parlance as the “manic pixie dream girl.” The list of characters that fall into this category is long: Sam Feehan (Natalie Portman) in “Garden State,” Allison (Zooey Deschanel) in “Yes Man,” Claire Colburn (Kirsten Dunst) in “Elizabethtown,” Polly Price (Jennifer Aniston) from “Along Came Polly,” Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) from “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World.”

Some of these characters are more nuanced than others in that the quirky women’s performance is filtered through how the men in their lives see them — a good example is Summer Finn (Deschanel again) from “(500) Days of Summer” — but the trope is well-trodden and exists for a reason.

That’s what makes Jane so refreshing as a character. While her unusual habits, wardrobe and mannerisms are decidedly funny, she doesn’t exist to be flattened or paired off, or spend the film languishing as someone’s sexual interest. To that point, her sexuality seems to be purposely scripted to be ambiguous. At the beginning of “Happiest Season,” she seems flirtatiously flustered by Abby; then just a few minutes later, she runs her hand down an old poster of a teenage heartthrob in her childhood bedroom and murmurs, “Is it hot in here, or is it just him?”

A lot of viewers posit that Jane is bisexual, as one Twitter user said, “I, and many other bis, [have] been the weird forgotten kid off to the side painting or writing fantasy stories is all I’m saying.” It’s all just speculation (and potential fodder for a sequel?) but that tweet gets at something that is actually more integral to the scripting of Jane’s character.

In pop culture, we see a lot of quirky adolescent girls — recent media is rich with examples, including the cast of “PEN15,” Missy (Jenny Slate) from “Big Mouth,” and Tina from “Bob’s Burgers” — who have deep, specific interests, ranging from Greek mythology, to Sylvanian Families dolls, to WWE wrestling, to horses to witchcraft.

Inevitably, there’s a narrative where those interests become almost like a homing signal for bullies, who tell them that they are too much or too weird. And while screenwriters sometimes flatten their female characters, often in real life, girls are taught to flatten themselves.

Jane, however, never did.

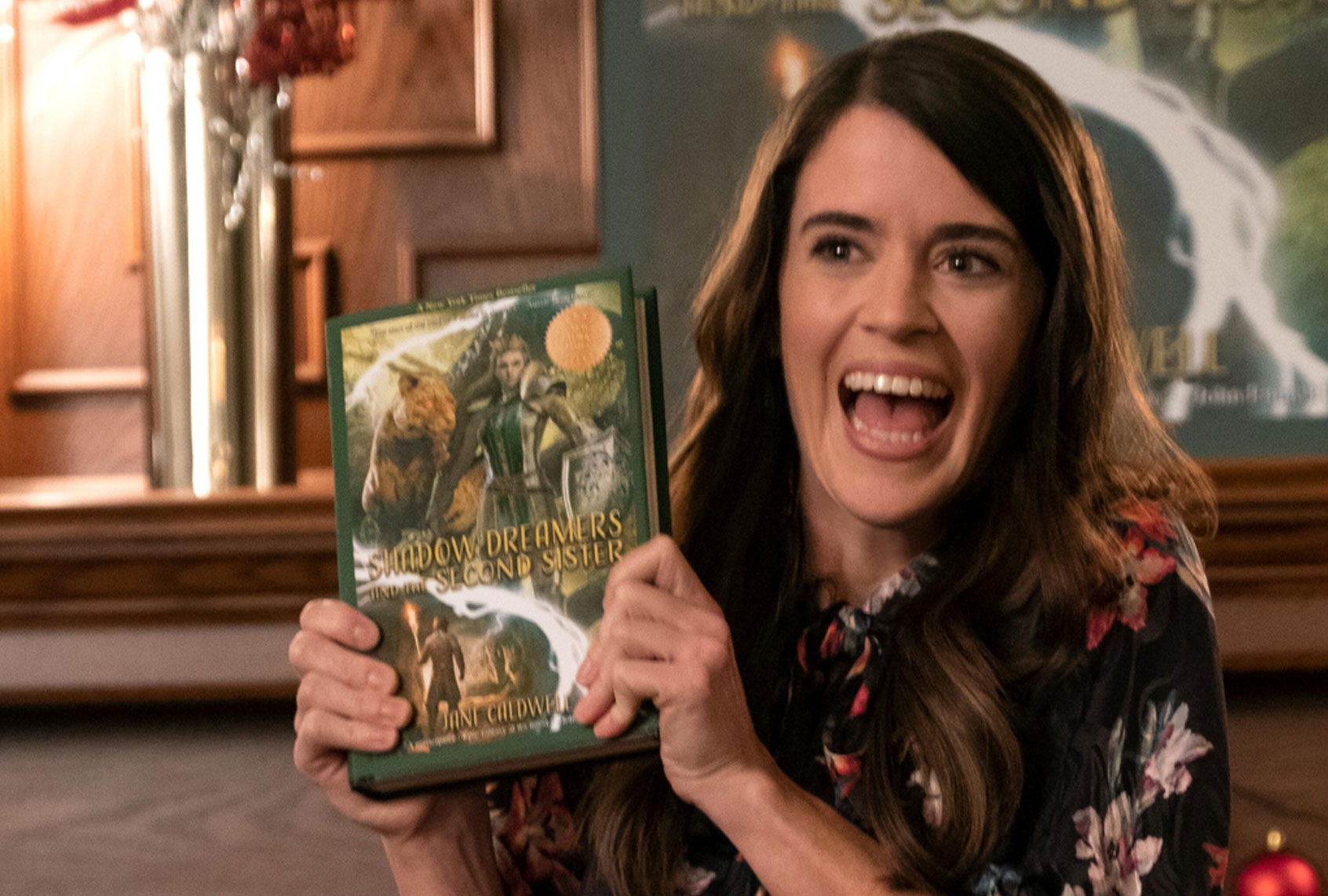

That’s why it’s so satisfying as viewers to watch things work out for her in the end. That moment when she’s finally holding up her complete novel, “Shadow Dreamers and the Second Sister,” all because John actually invested in her weirdness? It’s brilliant.

It’s unexpectedly poignant to watch her otherness be rewarded, and it is definitely her otherness that underpins Jane’s compassion for the people around her. This results in perhaps the best line in the movie, delivered by Jane after her Harper and Sloane reveal to their parents that, respectively, they are gay and getting divorced. She steps into line with her sisters and says, “I don’t have a secret, but I am an ally.”

And it’s exactly her otherness that makes Jane stand out in a film that otherwises lapses into both repression and schlocky holiday formula.

“Happiest Season” is currently streaming on Hulu.