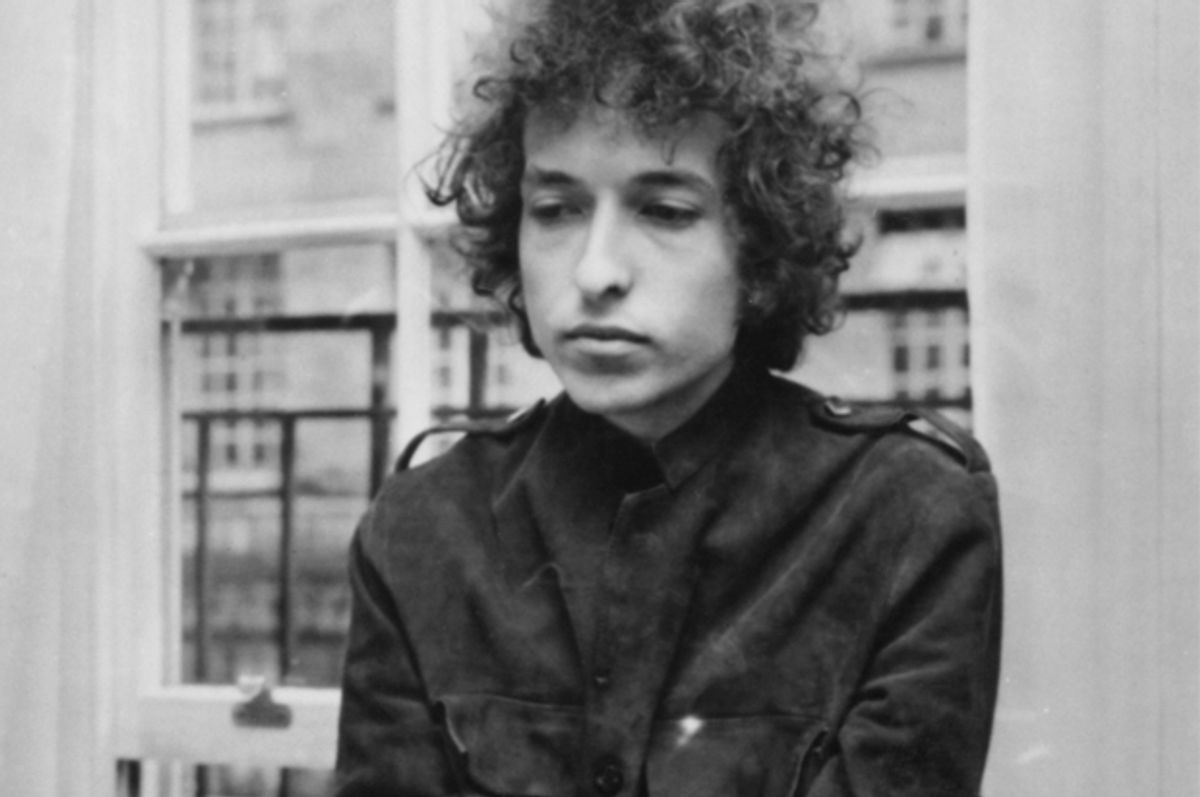

The news that Bob Dylan has sold his full publishing catalog to Universal Music Publishing Group, in a deal estimated to be worth more than $300 million, is a big surprise in the career of one of music's greatest songwriters. It's likely one of the biggest deals of this kind ever made. But what does the sale mean, exactly, for Dylan's songs? Here are the main takeaways from what's been reported so far.

All money generated by Dylan's prior work as a songwriter has a new recipient.

This deal concerns only the publishing rights for Dylan's existing songs — the music and lyrics for all of the 600 or so songs he has composed since his career began, and the songwriting royalties generated that way. That means that any time "Blowin' in the Wind," "Tangled Up in Blue," or any other Dylan composition gets streamed, sold, played on the radio, or used in a commercial enterprise like a TV advertisement or film spot, the songwriting royalty check that would have gone to Dylan will make its way to UMPG's bank account instead. (The same goes for any other artist's cover of a song written by Dylan — and for the Band's 1968 classic "The Weight," which was written by Robbie Robertson but whose publishing Dylan owned.)

Read more from Rolling Stone: Inside Operation Gideon, a coup gone very wrong

It's important to note that the deal only covers the publishing side of the two-lane road of music rights, not the recorded music side. Recall that Taylor Swift's $300 million catalog acquisition by a private investment group covered recorded rights but not publishing — the opposite of the Dylan sale. The owner of publishing rights typically controls whether or not songs are cleared for inclusion in TV, film, and ads; so, in Swift's case, that's Swift, and in Dylan's case, it's now UMPG. Which means…

Dylan's songs could start appearing in more movies, TV shows, and commercials.

Since Dylan has been more than willing to exploit his catalog this way in the past — memorably licensing his music to ads for Apple, Victoria's Secret, Cadillac, Pepsi and more — this seems unlikely to lead to a major shift in how often you hear his music in contexts like those. There could be more to come, though; if you find yourself wondering why "Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" is soundtracking a Peloton ad next year, you'll know who to blame.

Read more from Rolling Stone: The mother of Daisy Coleman, from "Audrie & Daisy," has died of suicide

Dylan's recorded output will stay the same.

This deal does not cover the master rights to Dylan's recordings — that is, the rights and royalties associated with any of the albums and songs he's released as a performer — so there's no more likelihood of Blonde on Blonde: The EDM Remixes or Freewheelin' 2 than there was last week. This also means that there should be no change to future installments of Dylan's ongoing Bootleg Series of unreleased vault recordings, which continue to be controlled by Dylan, his management, and his record company.

Read more from Rolling Stone: Rudy Giuliani hospitalized with COVID-19

Look for more catalog sales from major artists to come.

Dylan isn't the only one with this idea: In 2020, a flurry of major artists are striking huge deals to sell their catalogs to investors and music companies. Stevie Nicks just did the same, as have Jack Antonoff, Tom DeLonge, Richie Sambora, Imagine Dragons, and dozens of other acts. That's because these back-catalogs, in the evergreen era of streaming, have the potential to fetch their copyright owners a ton of money in the future. So artists and songwriters benefit by getting massive lump-sum payouts right now, in exchange for giving their revenue streams to new owners, who benefit by being able to scoop up whatever lucrative opportunities or streaming revivals are possible in the future. Since investors with deep pockets are still hungry for new deals, the fervor's not dying down anytime soon. Dylan will certainly not be the last major artist to sell their catalog for a huge sum — and there's still a whole host of classic acts out there who don't release music or tour anymore but certainly wouldn't balk at a nine-figure offer for their old rights.

Additional reporting by Amy X. Wang

Shares