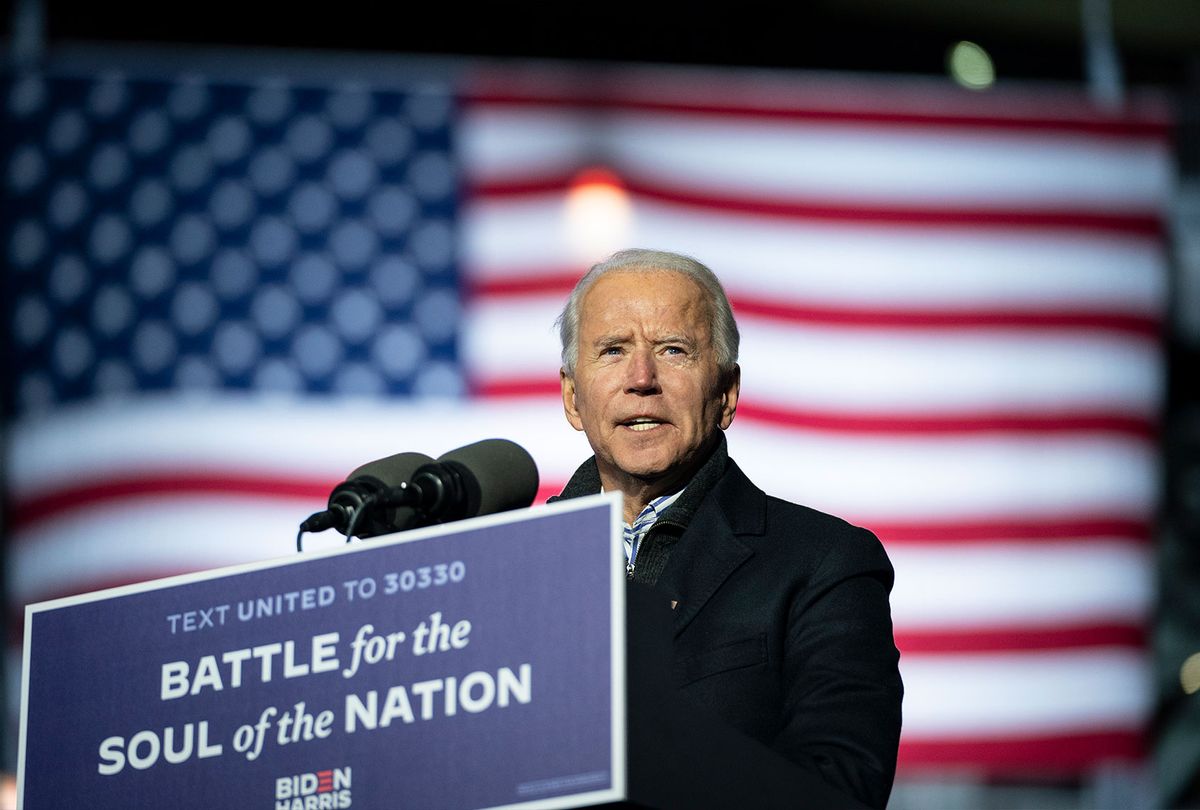

"It's time we address the structural inequalities in our economy that the pandemic has laid bare," President-elect Joe Biden said last week, as he introduced his economic team.

It's a good team. They're competent and they care, in sharp contrast to Trump's goon squad. Many of them were in the trenches with Biden and Barack Obama in 2009 when the economy last needed rescuing.

But reversing "structural inequalities" is a fundamentally different challenge from reversing economic downturns. They may overlap – last week the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit a record high at the same time Americans experienced the highest rate of hunger in 22 years. Yet the problem of widening inequality is distinct from the problem of recession.

Recessions are caused by sudden drops in demand for goods and services, as occurred in February and March when the pandemic began. Pulling out of a recession requires low interest rates and enough government spending to jump-start private spending. This one will also necessitate the successful inoculation of millions against Covid-19.

By contrast, structural inequalities are caused by a lopsided allocation of power. Wealth and power are inseparable – wealth flows from power and power from wealth. That means reversing structural inequalities requires altering the distribution of power.

Franklin D Roosevelt did this in the 1930s, when he enacted legislation requiring employers to bargain with unionized employees. Lyndon Johnson did it in the 1960s with the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, which increased the political power of Black people.

Since then, though, not even Democratic presidents have tried to alter the distribution of power in America. They and their economic teams have focused instead on jobs and growth. In consequence, inequality has continued to widen – during both recessions and expansions.

For the last 40 years, hourly wages have stagnated and almost all economic gains have gone to the top. The stock market's meteoric rise has benefited the wealthy at the expense of wage earners. The richest 1 percent of US households now own 50 percent of the value of stocks held by Americans. The richest 10 percent, 92 percent.

Why have recent Democratic presidents been reluctant to take on structural inequality?

First, because they have taken office during deep recessions, which posed a more immediate challenge. The initial task facing Biden will be to restore jobs, requiring that his administration contain Covid-19 and get a major stimulus bill through Congress. Biden has said any stimulus bill passed in the lame duck session will be "just the start."

Second, it's because politicians' time horizons rarely extend beyond the next election. Reallocating power can take years. Union membership didn't expand significantly until more than a decade after FDR's Wagner Act. Black voters didn't emerge as a major force in American politics until a half-century after LBJ's landmark legislation.

Third, reallocating power is hugely difficult. Economic expansions can be a positive-sum game because growth enables those at the bottom to do somewhat better even if those at the top do far better.

But power is a zero-sum game. The more of it held by those at the top, the less held by others. And those at the top won't relinquish it without a fight. Both FDR and LBJ won at significant political cost.

Today's corporate leaders are happy to support stimulus bills, not because they give a fig about unemployment but because more jobs mean higher profits.

"Is it $2.2tn, $1.5tn?" JPMorgan Chase chief executive Jamie Dimon said recently in support of congressional action. "Just split the baby and move on."

But Dimon and his ilk will doubtless continue to fight any encroachments on their power and wealth. They will battle antitrust enforcement against their giant corporations, including Dimon's "too big to fail" bank. They're dead set against stronger unions and will resist attempts to put workers on their boards.

They will surely oppose substantial tax hikes to finance trillions of dollars of spending on education, infrastructure and a Green New Deal. And they don't want campaign finance reforms or any other measures that would dampen the influence of big money in politics.

Even if the Senate flips to the Democrats on 5 January, therefore, these three impediments may discourage Biden from tackling structural inequality.

This doesn't make the objective any less important or even less feasible. It means only that, as a practical matter, the responsibility for summoning the political will to reverse inequality will fall to lower-income Americans of whatever race, progressives and their political allies. They will need to organize, mobilize and put sufficient pressure on Biden and other elected leaders to act. As it was in the time of FDR and LBJ, power is redistributed only when those without it demand it.

Shares