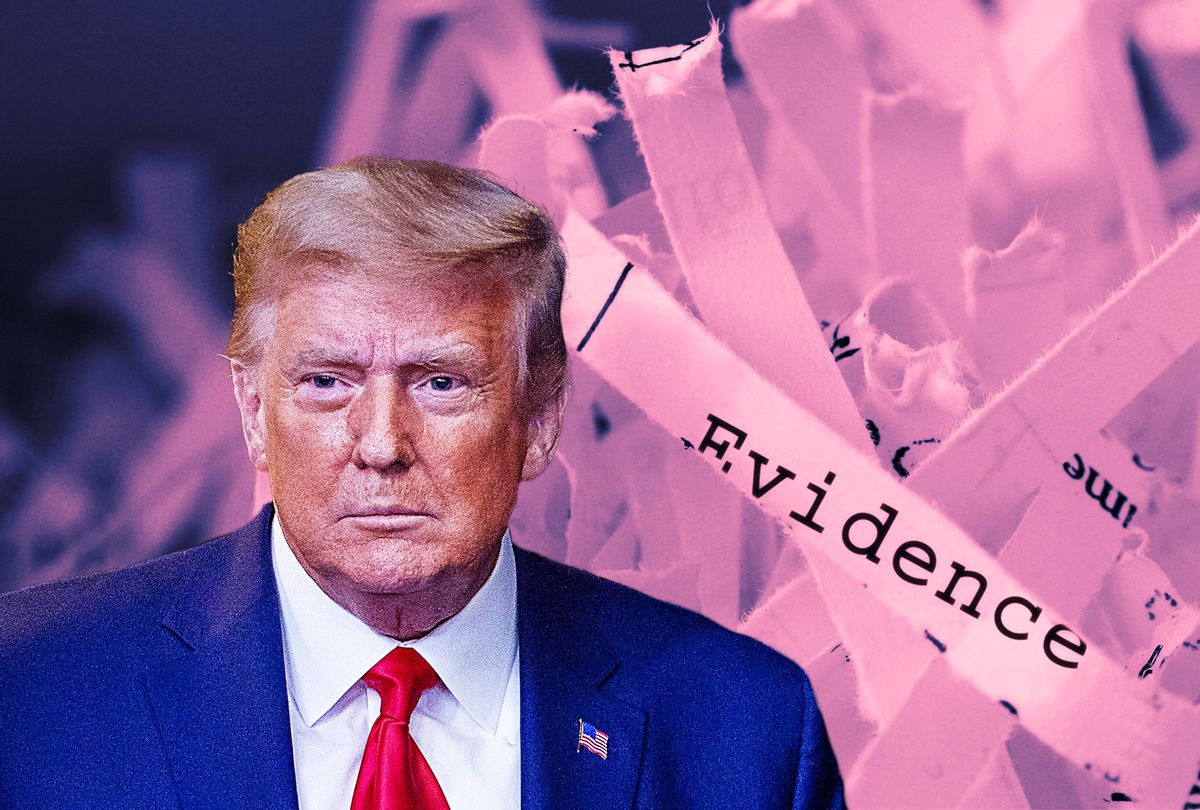

The news that Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield forced career staff to delete an incriminating email from a Trump political appointee is a red-alert moment for Washington-based reporters, who should fan out everywhere Trump loyalists may be destroying the evidence of their misdeeds as they head out the door.

"Reporters should start looking at that right now and start saying to the White House, to the executive branch agencies: 'What are you going to do to preserve documents?'" said Lisa Rosenberg, executive director of the wonderful pro-transparency group, Open the Government.

I interviewed Rosenberg because of her leading role in a brilliant new report full of recommendations for how the Biden administration should repair critical gaps in transparency, ethics and oversight. The report also serves as an excellent guide for how reporters should hold the next administration accountable. I'll have a lot more on that soon.

But first things first.

"One of the concerns we in the accountability community have right now is that there's going to be a wiping of all the computers — that all the documents are just going to disappear," Rosenberg said.

The potential scope of the problem is enormous, for obvious reasons.

"Donald Trump has absolutely no credibility when it comes to preserving documents," Rosenberg said. "He's been doing this all along: he deletes tweets, even though they're public policy; he rips up notes, when they're even taken — he rips up notes and some of his folks have to go and literally tape them back together again."

Another example: Greg Miller of the Washington Post reported last year that Trump "has gone to extraordinary lengths to conceal details of his conversations with Russian President Vladimir Putin, including on at least one occasion taking possession of the notes of his own interpreter and instructing the linguist not to discuss what had transpired with other administration officials."

"So we know that there's a history where there are supposed to be documents preserved," Rosenberg said, "but then they disappear or they vanish."

Of course it wouldn't just be Trump doing the destroying and deleting. "Because of Trump, and so many other folks that he surrounds himself with because of their history, there's a real risk that they're going to want to cover things up and hide things and prevent them from being embarrassed," she said. "Potentially to protect them protect them from legal liability."

Reporters can't just sit back and wait for the destruction to reveal itself, Rosenberg said. "Journalists can hold folks' feet to the fire. They can question people and they can remind people of what their duties are to preserve these records."

Specifically, that means reporting that these official documents belong to the public, not to the president. That means reporting on the relevant federal laws, including the Presidential Records Act. It means a particular focus on electronic records, because they are so much easier to destroy — no bonfire or shredding party necessary.

The history of presidential records law is relevant. From a 2019 Congressional Research Service report:

Following his resignation as President, Richard Nixon wanted to destroy recordings created in the White House that, among other things, documented actions he and others took in response to investigations connected to a burglary in the Watergate building and his reelection campaign. Under policy at the time, presidential materials were considered the President's private property. In response, Congress passed a number of laws to preserve the integrity of documents and other information related to Nixon's presidency and made those laws applicable to all future presidencies.

Enacted in 1978, the Presidential Records Act (PRA; 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2207) established public ownership of records created by Presidents and their staff in the course of discharging their official duties. The PRA additionally established procedures for congressional and public access to presidential and vice presidential information and the preservation and public availability of such records at the conclusion of a presidency.

Several other laws are applicable, too. Richard Painter, the former ethics counsel to George W. Bush turned virulent Trump critic, recently explained on Just Security:

Destroying or stealing documents belonging to the United States government is a crime. Destroying or stealing documents to cover up another crime, or activity that may be under investigation, is also a crime. Lying about what happened to missing documents is yet another crime. A departing federal official may take personal property from the office but no more. That includes perhaps some family photos — and of course that red cap. But everything else stays where it is. Anyone who doesn't understand that could end up staying with the government a lot longer than anticipated or desired.

Sadly, Trump is not the first president to make a mockery of records law. I extensively covered the George W. Bush administration's many successful — if duplicitous — strategies to escape retention rules.

"I actually think journalists are the key enforcers of the records documents right now," Rosenberg said. "And hopefully, they elevate the issue so that those good actors in the White House, if they see wrongdoing, if they see people covering up things, maybe they act, maybe they speak out, maybe there are whistleblowers."

Reporters should encourage staffers to go public — or, barring that, to report what they've seen internally. One option would be to report to an agency's inspector general, and insist that the IG request an immediate injunction, which would also make the issue public.

There are so many areas where Trump and his loyalists will face the judgment of history — if not of the judiciary — that it's hard to know what to worry about the most when it comes to the destruction of documents. But it's no surprise that the first solid evidence we've gotten relates to a cover-up of the Trump administration's inexcusable and tragic politicization of the failed response to the coronavirus pandemic.

As Dan Diamond first reported for Politico, one disappearing document we now know about was an Aug. 8 email sent by Paul Alexander, who at the time was scientific adviser to then-Health and Human Services spokesperson Michael Caputo. Alexander was trying to get career employees in charge of the CDC's canonical Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports to tone things down to match Trump's downplaying of the virus.

Rep. James Clyburn, who chairs the House Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, disclosed the deletion in a letter to Redfield and HHS Secretary Alex Azar.

Clyburn summed it up in a tweet:

Journalists should be concerned, too. They should make a full-court press on every source they have in the White House and the rest of the executive branch to root out any attempts to destroy the public record — before it's too late.

Shares