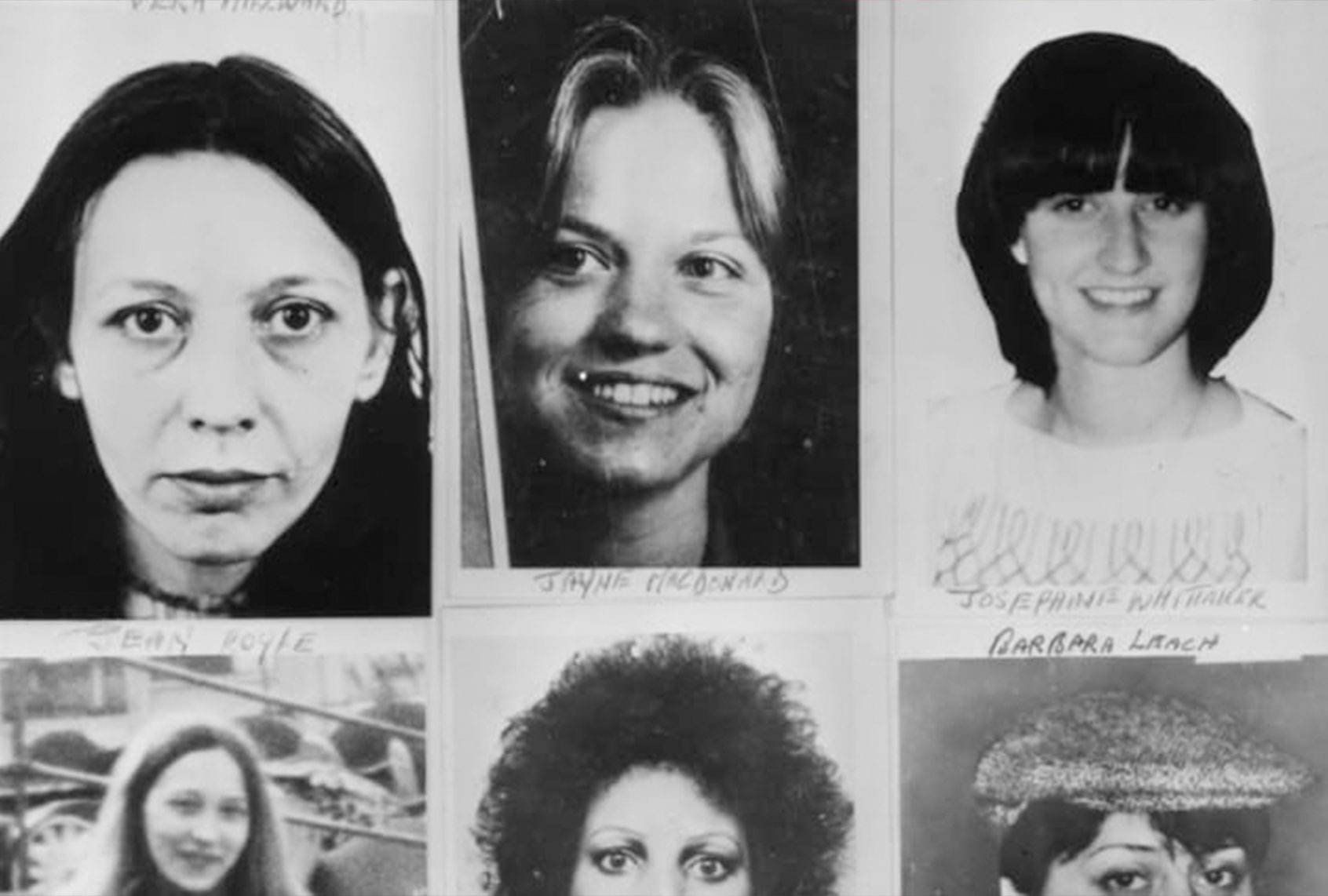

The Yorkshire Ripper had already murdered four women when police announced he’d killed his first “innocent.” Unlike the serial killer’s other victims, 16-year-old Jayne MacDonald was not a sex worker, and to the Yorkshire Police and the British press this signalled a shift in the case.

“For the first time, the national press were interested,” said journalist Christa Achroyd in the new Netflix docuseries, “The Ripper.” “Jayne was beautiful, she was 16 and, more importantly, the police had made a distinction between her killing and the killings of the other women.”

She continued: “They described her as the first ‘innocent’ and suddenly everything that happened before had happened to prostitutes, and here was an ‘innocent’ victim.”

The Yorkshire Ripper was the name given by the press to Peter Sutcliffe as an allusion to the 19th century serial killer Jack the Ripper. Both men specifically targeted lower-class women, sometimes sex workers, and often mutilated their victims’ bodies. While Jack the Ripper has never been identified, Sutcliffe managed to evade police for over five years, making it the longest murder manhunt in British history.

This case has received a flurry of new attention following the 2019 BBC docuseries, “The Yorkshire Ripper Files: A Very British Crime Story,” which detailed the many ways in which misogyny and the stigmatization of sex work dominated law enforcement’s investigation, from following false leads to dismissing pertinent evidence, as well as Sutcliffe’s death from COVID-19 in November.

Netflix’s “The Ripper” attempts to both capitalize on the renewed interest in the 45-year-old case, as well as offer “a sensitive examination of the crimes within the context of England in the late 1970s.” Unfortunately the victims’ voices are still lost along the way — an illustration of the way scripted and true crime continue to fail sex workers in their portrayals.

The first episode opens on the death of Wilma McCann, a mother of four whose body was found in 1975 on a playing field in the Chapeltown district of Leeds. Initially, this was viewed as a one-off act of violence, until three other women — Emily Jackson, Irene Richardson and Patricia Atkinson — were killed in a similar fashion over the next several months.

The police weren’t able to collect much physical evidence from the scenes, other than some boot and tire prints, but they developed an internal theory about the killer’s M.O. that soon went public: these murders were committed by a man who really hated sex workers.

Through modern-day interviews and a wealth of well-edited archival footage, “The Ripper” creators Ellena Wood and Jesse Vile create a vivid sense of life in 1970s West Yorkshire, which is not so much a backdrop for Sutcliffe’s crimes as a character in the story. Several industrial titans had left the area, meaning that jobs were scarce and economic stresses were skyrocketing. Some women turned to sex work to make a living, but when faced with violence were reluctant to go to the police for fear of potential arrest or futher assault. All of this was punctuated by a rising national interest in feminism.

The death of Jayne MacDonald — and law enforcement and media’s insistence upon her innocence in comparison to Sutcliffe’s prior victims — brought all these tensions to the foreground. Ackroyd, who was a young reporter at the time and serves as a sort of moral compass of this retelling, said that this forced the police to move beyond telling women that “didn’t have many boyfriends that they were fine.”

“The Ripper” methodically showcases the ways in which misogyny colored the response to the killings. Women were given an informal curfew, and sex workers were encouraged by police to leave town. Victims whose backstory wasn’t deemed consistent with Sutcliffe’s motives (meaning that they weren’t sex workers) were cast aside as accidents or attributed to different killers.

The series was poised to serve as an example of how modern true crime media could rectify the genre’s villification or erasure of sex workers and other marginalized communities, but it gets stopped up by its own contemporary talking heads, like “Yorkshire Post” journalist Alan Whitehouse.

When describing the police’s response to the killing of MacDonald, he states “this was the moment when West Yorkshire Police themselves were pulled up a little bit short, because until now they’d been dealing with a certain kind of woman following a certain kind of lifestyle.” Now, “a perfectly innocent girl, from a very ordinary family, is dead,” he said.

The series toggles between archival interviews about the cases where law enforcement’s contempt for sex workers is apparent, and current interviews with men like Whitehouse whose comments are still stained with shades of derision. Where the creators of “The Ripper” may have been wanting viewers to come away saying, “Wow, that’s horrible, but I’m glad times have changed,” they didn’t set up the dichotomous views they intended. There’s no interrogation of the ways in which the continued criminalization of sex work perpetuates physical and sexual violence.

This isn’t a huge surprise.

As Audrey Moore wrote in her 2016 essay, “Why I’m Fed Up Of The Way TV Portrays Sex Workers,” when you look for television shows where sex workers aren’t mocked or murdered, you’re left with very few options. Even comedies like “30 Rock” toss in lines like, “This is where we used to hold retirement parties. The balcony below is probably still littered with stripper bones.”

“In the vast majority of their programming, sex workers are treated one of two ways: as punching bags or punchlines,” Moore wrote. “Our lives are almost always sneered at, or pitied, or used as a symbol of inevitable tragedy. If you’ve ever watched police procedurals, or crime dramas, or thrillers, you’ve probably been offered a salacious glimpse of violence enacted on one of our anonymous bodies. Rarely given any agency or backstory as characters, we’re merely used to demonstrate the high-concept murderous impulses of a serial killer, or treated as collateral damage in the mission to save the morally ‘good’ characters.”

To its credit, “The Ripper” does not endeavor to humanize Sutcliffe, and it attempts to put names to its victims’ faces — literally. The names of the women Sutcliffe killed and attacked are printed frequently on the screen in big, blocky font next to static images of their faces. But ironically, through the series’ attempt to draw attention to how they were defined by their profession, they are still over and over reduced to just that.

It could learn a lot from “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” the HBO docuseries about Michelle McNamara’s best selling book of the same name on The Golden State Killer. As Salon’s Mary Elizabeth Williams wrote, the series was haunting in its portrayal of the very human details left in the wake of the crimes.

“When you think of the details around a case like the Golden State Killer, maybe you know about a recording of an ominous obscene phone call,” she wrote. “Maybe you visualize a disturbing police sketch of a cold-eyed suspect. But do you think of an anguished brother-in-law cleaning up a crime scene? Do you think of bits of food left out on a kitchen counter? Or a father struggling to work out what to tell his child?”

While “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark” does, these are precisely the details left out of “The Ripper” and often totally ignored by true crime media when the cases in question involve sex workers. Who is waiting for them to get home? What about their children? What do their families think?

In the case of “The Ripper,” we have some idea. Several days before the series released on Netflix, family members of Sutcliffe’s victims petitioned for the network to change the title of the series, several saying they had been interviewed under the impression that the show would be called “Once Upon A Time in Yorkshire,” which is far less salacious.

“The moniker ‘The Yorkshire Ripper’ has traumatised us and our families for the past four decades,” they wrote in an open letter. “It glorifies the brutal violence of Peter Sutcliffe and grants him a celebrity status that he does not deserve.”

While the series “The Ripper” attempts to dismantle some of that celebrity, instead putting police incompetence in the spotlight, it still neglects to truly center Sutcliffe’s victims. Perhaps it’s time to retire both the moniker and the same tired retellings of stories where sex workers are portrayed as one-dimensional or culpable in some way for the killer’s crimes.

“The Ripper” is currently streaming on Netflix.