What was I thinking?

That's the question I ask myself when I think of the winter of 1974. I was in Israel, writing about terrorism for the Village Voice — covering terrorism, if you will, as if you could cover something as horrific and capricious and criminal and essentially inscrutable as the attacks against civilians that were ongoing almost daily in Israel.

It was a year after the Yom Kippur War, only seven years after the Six Day War of 1967, and the Arab world wanted revenge after suffering yet another humiliating loss at the hands of the Israelis. So Palestinian militants were carrying out terrorist attacks against Israel almost nightly. A Druze family was killed in a terror attack less than a mile from the border with Lebanon, a dozen moviegoers were injured in a suicide bombing of a cinema in Tel Aviv, a rubber raft filled with terrorists was intercepted on a beach between Tel Aviv and Jaffa, and more attempts at invasion by sea were being made further north along the coast all the time. The attacks were so commonplace they rarely made the pages of the New York Times.

I was 27 years old, and what the hell did I know? I had been sent over to Israel because there was supposed to be another war with Syria, this time over the Golan Heights, but when I got there in early November, the threat of war had dissipated, and the Syrians had gone back to arming and funding Palestinian splinter groups and their terrorist networks, so almost by default, that's what I found myself writing about. There was, in fact, a war going on that no one was covering. It was the only war that a side with pipe bombs and AK-47s and RPGs could fight against the side with supersonic jets and nuclear weapons. It was a war of terror.

I was staying in a hotel on the beach in Tel Aviv. I would get a call from a source about a terrorist attack, go to wherever it had taken place and "cover" it, then I would write my dispatch for the Voice and hand it over the Israel Defense Forces censor to get it cleared as not being dangerous to Israel's national security. Then, sometime after midnight, I would hike over to the empty offices of the Westinghouse Broadcasting Corporation and pound away on their telex into the wee hours of the morning, sending my words off to New York.

I did this for weeks, and during all that time, I didn't have a clue that I was being watched by the Israeli secret services and being evaluated by spies for the Mossad to see whether I would be useful to them as a spy myself. Everyone had to hand in their copy to the office of the military censor. They used the process to keep watch on reporters, check out what they were covering, get a look at their political attitudes and general competence, and figure out if and how they could be influenced and used as witting or unwitting spies for Israel. I was innocent about spying. I had no idea what spies did or how they worked. Yet, as I learned, spies were all around me.

Sometime in mid-December, my friend John Broder and I decided it was time to travel to the place where most of the terrorism against Israel was being planned and prepared. We wanted an up-close look at Beirut. Broder was a runner at the Tel Aviv bureau of the Associated Press, which is to say he was a gofer around the office who occasionally got sent out on a story when the veteran reporters were either busy or asleep. He got the night shift a lot. We had "covered" a couple of terror attacks together, and Broder had told me he was tired of being a peon at the AP and was ready to quit if he could nail down a couple of assignments. I took note of his restlessness and called a friend of mine in Chicago who was an editor at Playboy and got Broder an assignment to write a story about terrorism for them. (Broder would go on to become bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune in places like Moscow and Beijing.) The Playboy editor wired $1,000 in expenses to Broder, and we started figuring out how to get to Beirut from Israel — not an easy task, as it turned out, and nearly impossible if you had Israeli stamps in your passport, which we both did.

The usual way to do it was to fly to Cyprus and change planes for Beirut, but Cyprus was in the middle of one of its many wars and the airport was shut down. Broder had a friend who knew a guy who had a friend who might know something about traveling to "Indian country," as Lebanon was called. We met the friend at a coffee shop on Dizengoff Street. He said he knew a guy who could help us with tickets and gave us a name and an address in Tel Aviv. The next day, we found the place at the end of a small alley off Ben Yehuda Street in a residential neighborhood, walked up a typical set of outside stairs and knocked on an unmarked door.

It was answered by a portly man in a white shirt who was smoking a cigar. He welcomed us into a room furnished with a steel desk and three metal office chairs and a phone. Nothing else. No lamps. No posters on the walls. He said he understood we were interested in traveling to Beirut. When did we want to go? What was our interest in traveling to such a dangerous place? Didn't we know there was fighting going on there between Palestinian factions, and it wasn't safe?

We knew all that, but we still wanted to go. He asked us more questions about what we knew and why we were so determined to go. We were journalists, we explained. We're writing about terrorism. He didn't take any notes.

I look back on the scene in that room today and wonder, what were we thinking? Did we think this sketchy guy was a travel agent? The plain room in an apartment building wasn't like any travel agency either of us had ever been to, nor was the guy with the cigar like any travel agent we had ever met.

After chatting for a half hour or so, he opened a drawer in the desk and removed one of those ticketing machines, the kind where you set a multi-page ticket on a horizontal slot and yank a slide back and forth that makes a coded airline imprint on the ticket. He pulled out a cardboard box full of little metal templates for different airlines and riffled through them. He explained that we would have to fly through Athens, and because we both had Israeli stamps in our passports, we'd have to change them for "clean" ones at the American embassy there. But not to worry. He knew a guy…

He consulted a calendar and a thick airline schedule book and made a couple of calls. Within an hour, he had finished writing tickets to and from Athens on TWA and tickets to and from Beirut on Middle East Airlines. He gave us the name of the guy at the U.S. embassy in Athens, and told us he would arrange the "clean" passports that would work with Lebanese immigration and customs. We would have to exchange them for our original passports on our way back. Without further ado, he pushed the tickets across the desk. Broder and I pulled out our wallets and asked him how much we owed him. He puffed silently on his cigar for a moment and smiled. "How does $25 sound to you?" "Each?" I asked, dumbfounded. "No. Twenty-five total."

He was a spy, of course. So was the guy at the American embassy in Athens, who was ready for us when we got there, even though we hadn't called ahead. Nominally some kind of cultural attache, he was actually in the CIA station at the embassy. He took new passport photos of us, and within 24 hours produced two legitimate U.S. passports that looked and felt used and had the identical visas from our original passports — minus the Israeli stamp.

When we met up with him to change our passports back a couple of weeks later, on our way back to Israel from Beirut, he was very interested in where we had been and who we had met and what we had seen, especially when we told him we had spent Christmas Day on the border between Lebanon and Israel. So was the "travel agent" in Israel when I conveniently "ran into him" at a restaurant in Tel Aviv after we had returned.

When I told him we had seen a guy on the street in Beirut whom we had met at a party in Tel Aviv before we left, he insisted that we meet at his "travel office" the next day. We told him the guy had been dressed in a business suit and carried a briefcase. He had recognized us at the same time we recognized him and turned casually to look at a display in a storefront window. We immediately realized we couldn't be seen with him and crossed the street and headed in the opposite direction. At the party in Tel Aviv, he had told us he worked for an electronics firm and traveled a lot on business. I'll say.

We asked our "travel agent" questions about the mysterious Israeli we'd seen in Beirut that he wouldn't answer. "Forget this guy," he instructed. "You never saw him." He asked if we had told anyone. We hadn't. He asked us not to write about what had happened. We agreed.

Several years later, I got to know a man in New York who had served in the OSS during World War II and still had connections within both the CIA and Mossad. When I told him about running into the Israeli agent in Beirut, he just chuckled. "Mossad has people everywhere. They can appear to be Arabs or Russians or Albanians or Turks. They are embedded everywhere. You've probably met some of them right here in New York." It turned out that I had. His partner, with whom he ran an international business I won't mention, and which you would never suspect was useful to an intelligence agency, was an agent for Mossad.

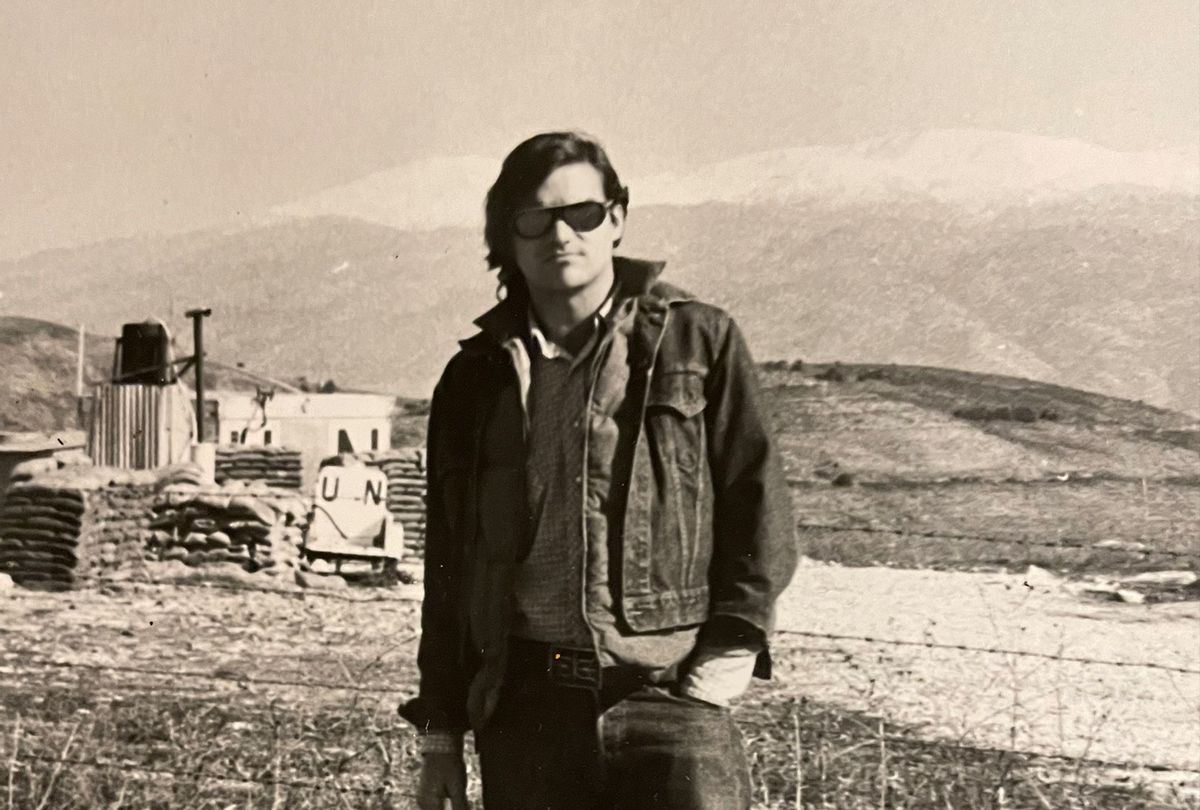

We could see artillery and mortar explosions on the blacked-out hills of the Deir Qoubel and Yinnar neighborhoods above the airport as we landed in Beirut. We were the only two passengers on our Middle East Air 727. Our new passports worked just fine when we passed through immigration at the totally deserted arrivals terminal. An AK-47-toting teenager stopped us on our way to the cab stand. Both of us had long hair. I was wearing cowboy boots and a Levi jacket over a grape-purple down vest I had picked up in Aspen. Broder was wearing a black leather jacket and Levis. The teenager made a motion like he was smoking a joint. Broder glanced at me and we nodded. The kid grinned. He took us for two hash dealers headed for the marijuana fields of the Bekaa Valley and passed us on.

Beirut was full of spies. There were hotels where spies were known to stay, like the Commodore, and bars where spies gathered to drink all over town. There was a Palestinian cab driver named Toufiq who waited outside our pension on Rue Mexique every day in his 1968 Oldsmobile 88. He was a spy for the PLO, or Fatah or the PFLP — for somebody, anyway. It was his job to keep tabs on us and report where we had gone and what we had seen and what we were likely to write about. We had heard the PLO had files on every reporter in town, and it was true. Toufiq had read everything I had written for the Voice from Israel, and even some of the AP dispatches Broder had managed to file. He later told us he knew our names before we introduced ourselves.

Toufiq would honk for us if he heard there had been a terrorist attack somewhere in town, then he would drive us at breakneck speed through the insane Beirut traffic and translate for us when we got there. We always wondered if he translated our questions accurately. He could have been taking sides, seeking to influence us, pitching a dispute between Palestinian factions one way or another. We never knew. We just wanted to be close to the action. There were terror attacks everywhere, all the time. We had a hard time figuring out who was who and why they were bombing and shooting each other, but it didn't really matter. It was terrorism. We were in the middle of it all. We were writing about it. Beirut was heaven. We were both in our 20s and we had wings.

We were told by a friend of Broder's in the AP Beirut bureau that we should assume we were followed everywhere we went. We never saw anyone tailing us, but then we had Toufiq driving us everywhere we went and translating for us. They didn't need anyone else to follow the two hippie-looking goofs who were going around Beirut asking questions, hauling out cameras and notepads everywhere they went.

The border with Israel was a no-go zone. Everyone told us to stay away from it. You couldn't get there anyway, they said. There were roadblocks everywhere — one Palestinian faction controlled this village, another faction controlled that one. The whole region, all the way from the Golan Heights in the east to the Mediterranean coast, was an armed camp with UN peacekeeper outposts scattered throughout the no man's land between the border fences. There were Israeli patrols on the other side of the border.

We had to go. It was surprisingly easy to talk Toufiq into driving us down there. We had dinner on Christmas Eve at the pension and left early on Christmas morning. Toufiq thought he knew a route where we wouldn't run into too many roadblocks and headed southwest, toward the Golan Heights. We could see crumbling Crusader castles on hilltops. Hillsides were lined with stone-walled terraces, and we could see old men and boys plowing behind plodding oxen. It was like we were in the 3rd century, and we were less than 20 miles from Beirut.

Toufiq talked us through a couple of roadblocks and by mid-morning we were in the foothills of the Golan Heights. We could see scattered Israeli farmhouses across the border. We parked outside a medieval stone village with cobbled streets no wider than a donkey cart. Toufiq scared up the mukhtar, the village mayor, and he took us around, pointing to damage the village had suffered from bombing by Israeli jets. He told us Fatah used to hide their technicals — pickup trucks with bed-mounted machine guns — under the olive trees. The Israelis figured it out and now large swaths of olive groves had been flattened by bombing, and the villagers couldn't earn their living from olive farming anymore.

We turned a corner on a narrow village street. The hoods and windshields of pickup truck technicals were visible just inside the front rooms of several stone homes. The street-side walls had been removed and the trucks backed far enough into living rooms and bedrooms that they could not be seen by Israeli jets overhead.

Suddenly a guy in a headscarf appeared, and Toufiq grabbed my arm, pulling me back around the corner. "Not good," he said. We ran back along the narrow street and hopped into the Oldsmobile. Toufiq fired the engine and we backed up. He spun the wheel and floored it down the narrow road up the hill to the village.

I heard gunfire and turned around to find one of the technicals following from a distance. I could hear the machine gun rattling as I hit the floor of the backseat, trying to dig my way through to the car's undercarriage. I looked up at Broder. He was hanging out the window with his camera, taking pictures.

Toufiq's Olds 88 was faster than the pickup, and we soon lost them. But now they knew we were there, and our jaunt along the border was over. Toufiq turned off the border road and made his way northwest for the coast. We ate our Christmas dinner at a seafood restaurant on the harbor in Tyre where Alexander the Great had laid siege to the city. We left as it grew dark.

That night, as we drove through the ancient city of Sidon and north to Beirut, Toufiq told us a story about a family of spies: his own. He and his three brothers had been born in Haifa — then in British-administered Palestine, now in Israel. As a young man, Toufiq made his way to Lebanon to join with other Palestinians in exile. His mother, however, chose to remain in Haifa in a house that had been in their family for more than 100 years, where she gave birth to three more sons.

When his brothers were young, before they left home, Toufiq would sneak across the border into Israel and visit his family in Haifa. But after his brothers had grown up and joined him in exile, it was too dangerous for all four of them to cross the border to visit their mother, so she began to smuggle herself across the border to visit them.

One night she was caught crossing the border by Israeli authorities and jailed. The next day when she went to face the judge and he asked her how she pleaded, Toufiq's mother asked the judge if he had chickens when he was growing up. He said that he had. She asked him if he remembered how mother hens behaved with their chicks after they were born, gathering them under her wings at night to protect them and keep them warm. The judge remembered.

"Well, judge, I am that mother hen, and I plead guilty."

The judge fined her 50 Israeli pounds. Toufiq's mother looked up at the judge as she paid her fine to the clerk of the court. "Here is my 50 pounds, judge," she said, counting out the money. She continued to count out more bills. "And here is another 50 for the next time I go north to visit my chicks, and another 50 for the time after that."

The whole of the region, from the village we had visited that morning to the harbor where we had enjoyed our Christmas dinner, had been conquered over and over and over again through the centuries. We passed Roman ruins as we drove into and out of Tyre. The Romans had conquered the Seleucids in order to take Tyre, which meant they had spied on them. Before the Romans ruled, the Seleucids had spied on the Greeks, who had spied on the Persians, who had spied on the Babylonians, who had spied on the Assyrians, who had spied on the Phoenicians, who had spied on the Egyptians, who had spied on whatever tribes of ancient people had been living in the hills and valleys when they got there with their armies. We had been driving through a land of spies all day.

Spying was like a bacterium in the soil, a strand in the DNA of a place that had been fought over since before humans were able to record history. Now it was 1974, and everyone was still spying on everyone else. It was Christmas in Beirut, and all through the house, if a creature was stirring, someone was watching.

Shares