Now that Donald Trump has gone full Lukashenko in his now-violent plot to retain power, we have to ask whether this time, finally, the nation will muster the collective will to hold him responsible for his malfeasance. The future of American democracy may depend on how the question is answered.

Even before Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6 to disrupt the joint session of Congress that had convened to certify Joe Biden's Electoral College victory, Trump had committed a variety of fresh federal and state criminal offenses in his hour-long telephone conversation with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger on January 2. In the call, the sitting president of the United States pressured Raffensperger and Ryan Germany, the secretary's general counsel, to "find" him enough votes to overturn Biden's win in the state.

As two recounts and a signature audit have confirmed, Trump lost Georgia by precisely 11,779 ballots. Nonetheless, Trump made it clear toward the latter part of his talk with Raffensperger that he wasn't just asking for an outlandish favor. Rather, he was making a demand, and serving notice in his official capacity that both Raffensperger and Ryan could face federal prosecution if they refused to comply.

Don't accept this interpretation of the conversation from me. Take it from Trump himself. Trump has acknowledged on his Twitter accountthat he made the call, and the Washington Post, which broke the story, has published a complete transcript of the conversation, in which Trump was joined by White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and several lawyers, including prominent conservative attorney Cleta Mitchell.

The Washington Post has also released the complete audio recording of the conversation and you can listen to Trump's own words:

"That's a criminal offense," Trump can be heard saying, accusing Raffensperger of reporting false election results. "And you can't let that happen. That's a big risk to you and to Ryan, your lawyer.… And you can't let it happen, and you are letting it happen. You know, I mean, I'm notifying you that you're letting it happen. So look. All I want to do is this. I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have, because we won the state."

Realizing the need for action, two Democratic members of the House of Representatives—Ted Lieu of California and Kathleen Rice of New York—have written FBI Director Christopher Wray, asking for a criminal investigation into Trump's threats. Citing two federal statutes and a Georgia law, Lieu and Rice wrote that they believe Trump has "engaged in solicitation of, or conspiracy to commit, a number of [federal and state] election crimes."

Lieu and Rice might also have added treason and sedition to the list, but they drafted their letter before Trump supporters rioted at the Capitol.

Unfortunately, there is still little chance that Trump actually will be prosecuted for the phone call. Federally, as Biden's inauguration approaches, Trump can be preemptively pardoned for any crimes, either by resigning and permitting Mike Pence, as his successor for the few days remaining in the lame-duck period, to do the honors or by issuing a pardon to himself. And as for Georgia, no one should expect an indictment as long as the levers of state government remain in Republican hands.

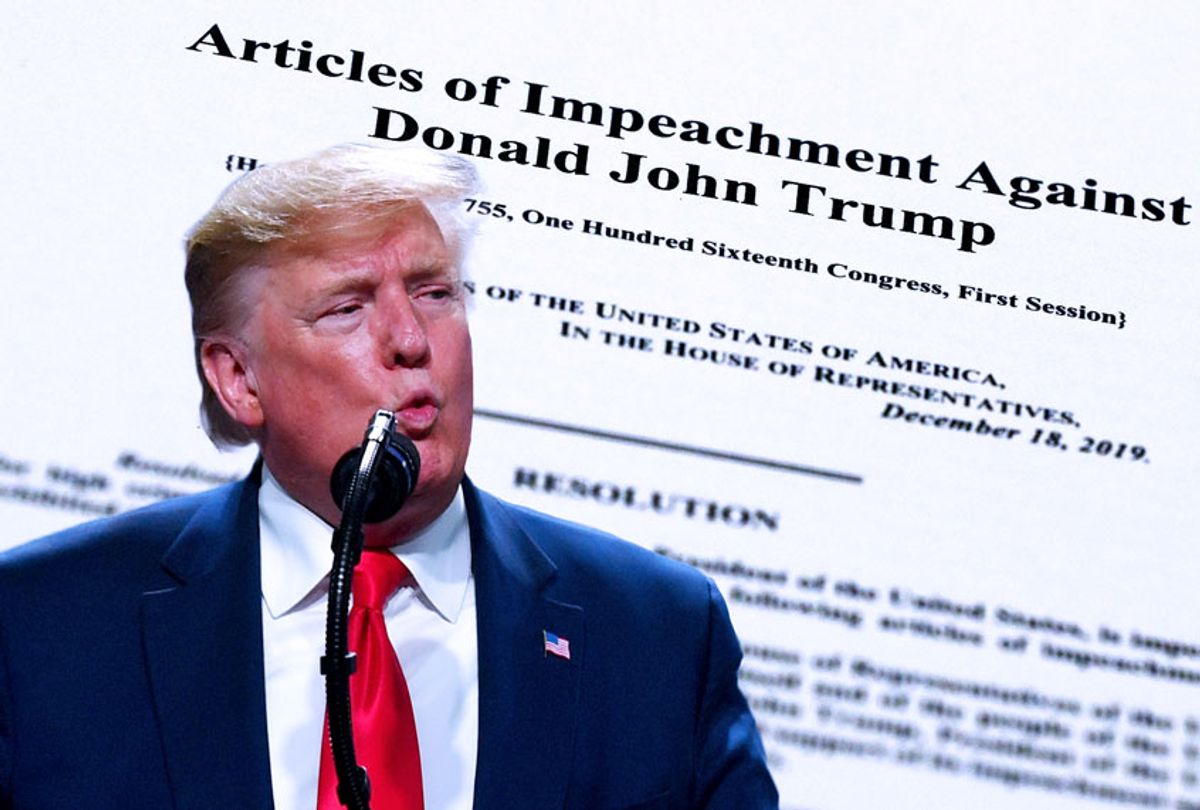

There is another way to hold Trump accountable, however—by means of a second impeachment.

The goal of a second impeachment would not be to remove Trump from the White House, unless, of course, he somehow manages to pull off a coup d'état before January 20. The goal would be to disqualify Trump from ever holding federal office again.

Under Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution, judgment in cases of impeachment extends to both sanctions—removal from current office and disqualification from holding future office. Since Trump reportedly has floated the idea of running for president again in 2024, a second impeachment would be designed to deal a death blow to another Trump campaign with hearings in the House and a trial in the Senate focused on the "high crimes and misdemeanors"—the phrase used in Article II of the Constitution to define impeachable offenses, along with treason and bribery—that Trump committed in his first term in office. Impeachable offenses, moreover, are not subject to the pardon power.

A second set of impeachment articles returned against Trump could allege a bundle of serious crimes in addition to the phone call to Raffensperger, ranging from obstruction of justice in connection with former Special Counsel Robert Mueller's probe into Russian interference in the 2016 election to conspiracy to defraud the United States by subverting the entire 2020 election.

Nor would the fact that Trump was no longer president legally bar a second impeachment. In 1876, the Senate conducted an impeachment trial of Secretary of War William Belknap even though he had resigned before the House voted to impeach him for financial corruption. Although the Senate failed to muster the two-thirds majority needed to convict Belknap, a majority of senators found him guilty. His impeachment trial lasted nearly four months and featured more than 40 witnesses.

While Richard Nixon escaped impeachment via resignation, the current House and Senate would not be bound by Nixon's example. Both chambers would be free instead to follow the Belknap precedent in the case of impeaching a former president, as several leading constitutional scholars indicated in interviews with the Washington Post in 2019.

If he were faced with a second impeachment, Trump wouldn't get off as easily as he did the first time around. He would still have to be convicted of an impeachable offense by a two-thirds Senate majority, but as Amherst College professor Austin Surat argued in a USA Today column published January 4, only a simple majority vote would be needed for disqualification. The National Review's Kevin D. Williamsonhas also called for a second impeachment.

The bottom line is that Donald John Trump, our 45th commander in chief, must be brought to justice by any legitimate means. With the House in Democratic hands and with enough Republicans in the Senate fed up with Trump's sedition, a second impeachment is not only possible—it is a necessity.

This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute.

Shares