Last June in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Amber Ruffin opened four episodes of NBC’s “Late Night with Seth Meyers” by telling stories about her own traumatizing run-ins with racist cops. In one she recalls an officer pulling her over and, for no reason, screaming at her until she burst into tears. At the time of this encounter, she was teenager.

In another, the “Late Night” writer and host of “The Amber Ruffin Show” on Peacock recalls the time cops threatened her for joyfully skipping down an alleyway to meet a friend she hadn’t seen in a very long while.

In yet another tale an officer tried to bust her for soliciting because she was sitting in a car with a male friend. Yes, that friend was white. No, they weren’t doing anything wrong. She wasn’t breaking the law in any of the other instances, either. I would love to say this goes without saying, but . . . it doesn’t.

“Look, I have a thousand stories like this,” Ruffin shared with viewers. “The cops have pulled a gun on me. The cops have followed me to my own home. And every Black person I know has a few stories like that.”

If the realization that the perky, friendly Ruffin was subjected to police harassment many times shocked you, wait until you read about the craziness her big sister Lacey Lamar has survived.

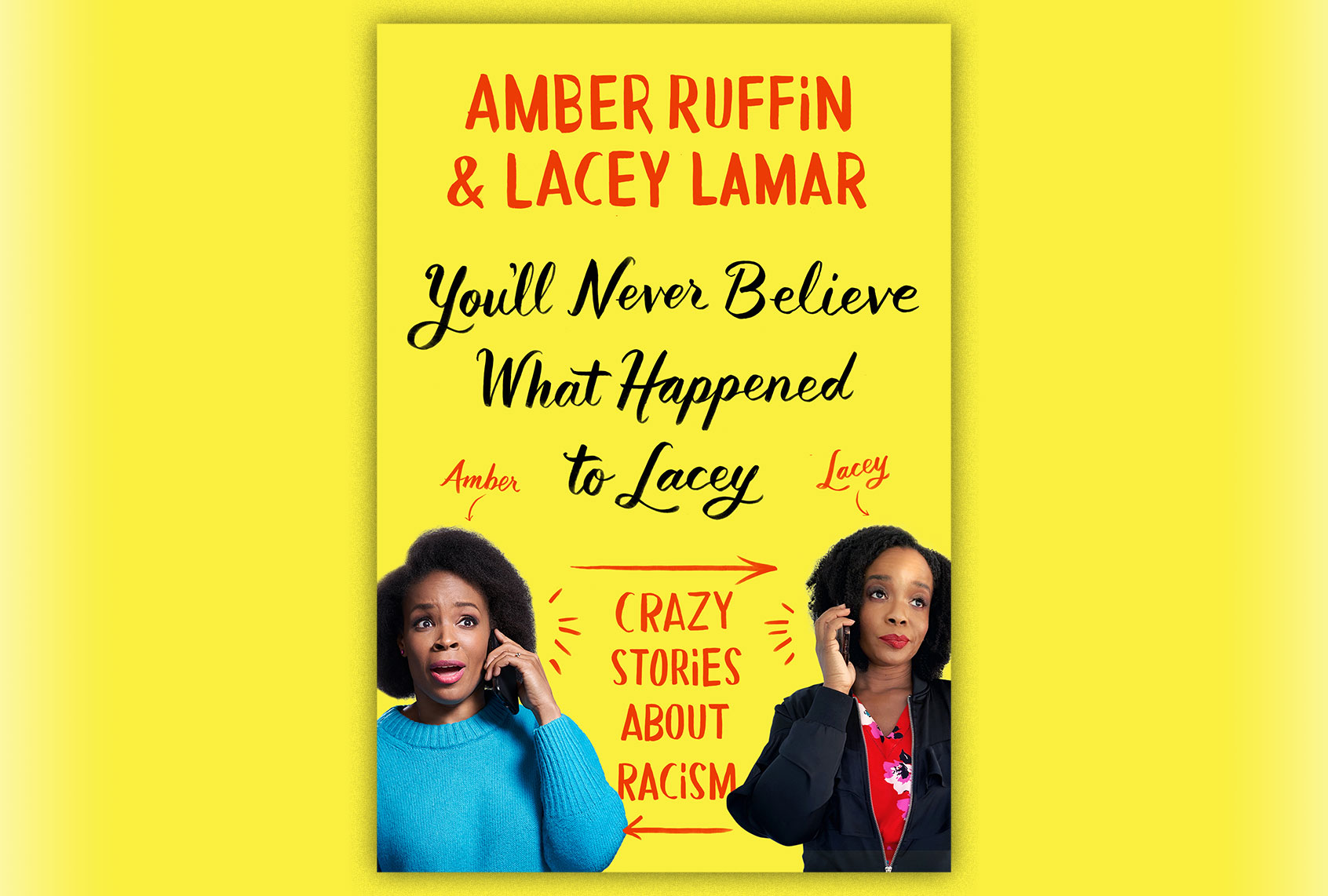

Ruffin and Lamar’s new book “You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacey: Crazy Stories About Racism” was released on Tuesday, and for obvious reasons the timing of its debut is in some ways unfortunate and in others, perfect. Last week’s violent insurrection perpetuated by white supremacists makes two things crystal clear.

First, our inability to talk in plain terms about racial inequality is killing our democracy. Second, for all of the reading so many white people were supposedly doing, the fact remains that a lot of folks have to be entertained into actually learning something. Enter this timely and timeless book that is hilarious, insightful, aggravating and comforting in equal measure.

Lamar and Ruffin stress that it is not their intent to fill a book with sad stories of their brushes with (or significant exposure to) racism in Omaha, Nebraska, where Lamar still lives. Instead they want to convey with absolute, comedic absurdity of the run-of-the-mill bigotry that Lamar has contended with all of her life, ranging from being profiled while shopping to enduring out-and-out discrimination and abuse in multiple workplaces.

“You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacey” is inspired by the numerous texts and calls the sisters exchanged over the years. If Ruffin has a thousand stories, Lamar’s memory is a veritable trove of outrageous incidents because Ruffin says her sister is a lightning rod for white supremacists with no internal editor. “She’s the perfect mix of polite, beautiful, tiny and Black that makes people think: I can say whatever I want to this woman. And I guess you can,” Ruffin writes.

“You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacey” will impact readers in various ways, which they address in the preface. White readers, fingers crossed, are going to read it and, in Ruffin’s words, “maybe walk away with a different point of view of what it’s like to be a Black American in the twenty-first century.” Black people will recognize most of Lamar’s stories because some version of it has probably happened to them, and the sisters hope that lets them know they’re not alone.

The book’s publication enables them to be together this week in New York, where “Late Night” is in production. Salon was able to catch them for a conversation over Zoom on Tuesday, where they were enjoying each other’s presence for the first time in a very long while. The following transcript of our chat has been edited for length and clarity.

This book came out this week, and its release also happens to coincide with a very interesting time, to put it mildly. Obviously this was not planned. But did you two have any conversations about the circumstances?

Lacey Lamar: Just that the thing that sticks with me the most is when all this was happening, people were like, “This is not who we are.” Yes, it is. I could have seen this coming.

There’s a little story in the book about two ladies that I worked with that were supervisors who were extremely militant, scary as hell, and said, “You know, one day we’re just going to get a commune together and, you know, we’ll only have certain people. Definitely not –” And they named a few races and because I was standing there, they didn’t say Black people. But it was implied.

And they said, “If anyone comes, you know, if I’m able to see them, I will shoot them and kill them.”

Amber Ruffin: And these are all women!

Lamar: So yeah. Not surprised all that [the insurrection] happened.

Even the title itself, which I want to talk about, speaks to that idea that folks don’t necessarily believe because they maybe either can’t picture or accept that these stories happen. So let’s talk about the title. I want to know whether it was very intentional to use the word “believe” in the title.

Ruffin: It was not. Maybe from Lacey’s angle, but you know, I’ve lived in a big city for the past 20 years, so I really do mean it when I say, “You’re not going to believe it.” Because almost everyone I talk to is like, “This is a crazy, constant injustice!” But when Lacey’s friends read this, they’re going to be like, “What’s your problem?” (She laughs.)

Lamar: Every time I hear the title I hear Amber’s voice saying that. Because when we get together for our family reunions, we always go out that evening and we do karaoke. And all of our old friends all get together, and Amber must say it three or four times a night. “Oh my God, guys. You’ll never believe what happened to Lacey.” And she’ll go into this story, and I’m like, “Oh God, I forgot about that.” Seriously, it’s said every time. So when I see that title I picture Amber telling one of my stories and cracking up.

Ruffin: “You’ll never believe it.”

How often were you sharing these stories?

Lamar: Oh, all the time. All the time . . . And a lot of the time I am sharing these stories at work to white racist people to tell them, “Oh, you need to stop doing this. You know, for instance, this happened to me . . .” And I’m telling the story and they’re like, “Okay. Yeah, I can see where you think that that’s bad. Okay.” So there’s that.

Do they learn?

Lamar: Sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t.

Ruffin: It’s a fun surprise.

“You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacy” is structured to read like you two are sitting in the same room and having this back and forth conversation.

Ruffin: That just naturally happened because I knew I wanted it to be conversational. You know, when you’re having a conversation and you go, “Oh my gosh, I had two eggs this morning and that is too many.” And then your friend goes, “Well, I had three. And then your other friend goes, “You’re never going to believe, but this one time I had four!”

That’s just that’s how normal conversations go. So I just built the stories from small to big, in a lot of ways. But in other ways, it kind of hops all over the board. I really wanted the throughline to be that you can believe these stories at the beginning, but by the time you get to the end, your head is in your hands. You cannot believe this is happening.

I love that you have a chapter title that reads “I Want to Put This Book Down and Run Away From It,” simply because as much as I found these stories to be very entertaining, they were difficult to stomach at times. I actually did have to put the book down because it was dredging up bad memories for me and making me angry. I can only imagine what that process must have been like for you to remember them and write them down. Because this is a critical mass of stories you’ve presented.

Lamar: It’s a heavy read at times. You know, I think I’ve read the book completely through three times, but some of the stories I just skip over because it brings you right back there. And the worst story for me, probably isn’t one that people think, but it’s the worst story for me because I feel like it happened yesterday. It’s the story where one of the supervisors is reprimanding me for greeting the little white girl. I mean, it was humiliating. I’m like, “Are we in 1910?” Just the anger that I felt. Like, are you kidding me? And having to sit through that and go around the room and everyone’s like, “I can’t believe you did that, Lacey. That was so rude. Do you know how to talk to people? Do we need training?”

And it went on for 41 minutes and I’m looking at the clock. And at some point I just block it out and I start, in my head, going, “Okay, if I walk out of this job today, how much money do I have to last until I find another job?” That’s all I was doing was calculating . . . because I was just done. I was not going to be working there any longer. So yeah, that story? I wrote it, I’m done. I’m probably not going to read that again because it does weigh you down. But we tell these stories so much that the sting is gone for most of them.

Amber, were there any stories for you that had that kind of weight to them?

Ruffin: Not really, but they had different effect. Reading this book I feel, and I don’t know if this is sick or not, but I feel comforted, you know? I feel like, “All your little garbage, Amber, does not add up to all of Lacey’s garbage, and she’s fine.” So I’m probably fine, you know?

Also, because all of these stories made a real book that was published and is bought gives you validity. And you’re like, we are correct. Does that sound crazy?

No.

Ruffin: But we are right. Because this book is kind of hopefully breaking the air of like that white thing where you work at a predominantly white place and you, no one ever says “Don’t bring up racist things that have happened to you”? But you know that that’s the rule. This, for me, breaks that wide open and that feels so good to me. I can’t even tell you. So all these stories make me feel good, and the worse the better. Because I like it when bad things happen to my sister. I like that! Just kidding.

Looking at this book in the context of when it’s coming out and people picking it up in the wake of recent events, what are you hoping it will can add to the dialogue?

Ruffin: I hope that it gives people a little bit of a vocabulary, because once you look at the wide array of these stories, then you can take racist happenings and put them on a spectrum. And then you take that whole spectrum and you pick it up and you shift it all the way over to very, very bad, you know? Once, you hear Lacey say “This happened to me and I didn’t like it” – OK. The 40th time, she says that you go, “Oh, okay, this is a big problem. And it is rampant. And I’ve got to pick a side.”

In the book you describe what Lacey looks like, that she’s small and adorable – and basically telling us that it doesn’t really matter how we look or how we’re dressed or whatever it is. These incidents happens to every Black person.

I want talk about that specifically because Amber, I think part of the reason that people connect with you, besides the fact that they see you are very funny and talented, is that you have a very friendly demeanor that allows people to have an openness to these stories. When you told your police harassment stories on “Late Night” people were like, “Wait a minute, this happened to Amber Ruffin? Not our Amber!” Not everybody can do that.

Ruffin: You know, when I started out on “Late Night Seth” I wasn’t really talking about race and stuff. I was dressing like a doctor and, you know, diagnosing people with the farts or whatever we thought was fun.

When they realized that their favorite fart-solving doctor – and now I wish I hadn’t chosen that as an example, but here we are! – that their favorite Dr. Fart has suffered a ton of racism, I think people were taken aback and then they kind of looked around and were like, “Wait, is this everybody? Okay. But to what degree?” Well, to this degree.

After George Floyd’s murder I went on “Late Night Seth” and I opened each show with a different story that had happened to me. They’re all in the book. Each story was a different time when I was harassed by a cop. And I had, by this point, said a million things about race on the show.

I thought white people were going to hate my guts because I said this out loud but then, you know, the pandemic hit.

. . .Maybe in my six or seven years here, I’ve received three pieces of fan mail. When I got back to work, there was a big old pile of letters. And they each said basically the same thing, which was, “I cannot believe that this happened. And I especially can’t believe it happened to you because I feel like I know you. So how insane must these cops have been to be behaving this way?” And they seemed like they understood it all the way around, because then they were like, “And then once I reconcile these two things, I have to look at any role I may have played. And the answer is, I did.” And I’m like, Oh my God, these people are all overstanding.

So I thought that was very moving. Not as moving as when Black people go “Amen,” because there ain’t nothing better than that, but you know, it was great.

Lamar: Um, I have been told several times at work, like, “Oh, you just seem so sweet and nice.” So then when you tell them something has happened to you they’re like, “Oh, well I can’t imagine that happening to you.” So I get that a lot, where people are like, “Why would this happen to you?” You just appear to be this certain way and not the stereotypical way that they picture Black people.

Ruffin: Yeah. It’s crazy that white people think that there’s a way that you can behave that warrants the crazy things that have been happening. That there’s a group of people that deserve that treatment, but it’s not you. It’s the other people, which is what people are saying. And that’s insane.

“You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacey: Crazy Stories About Racism” is on sale now.