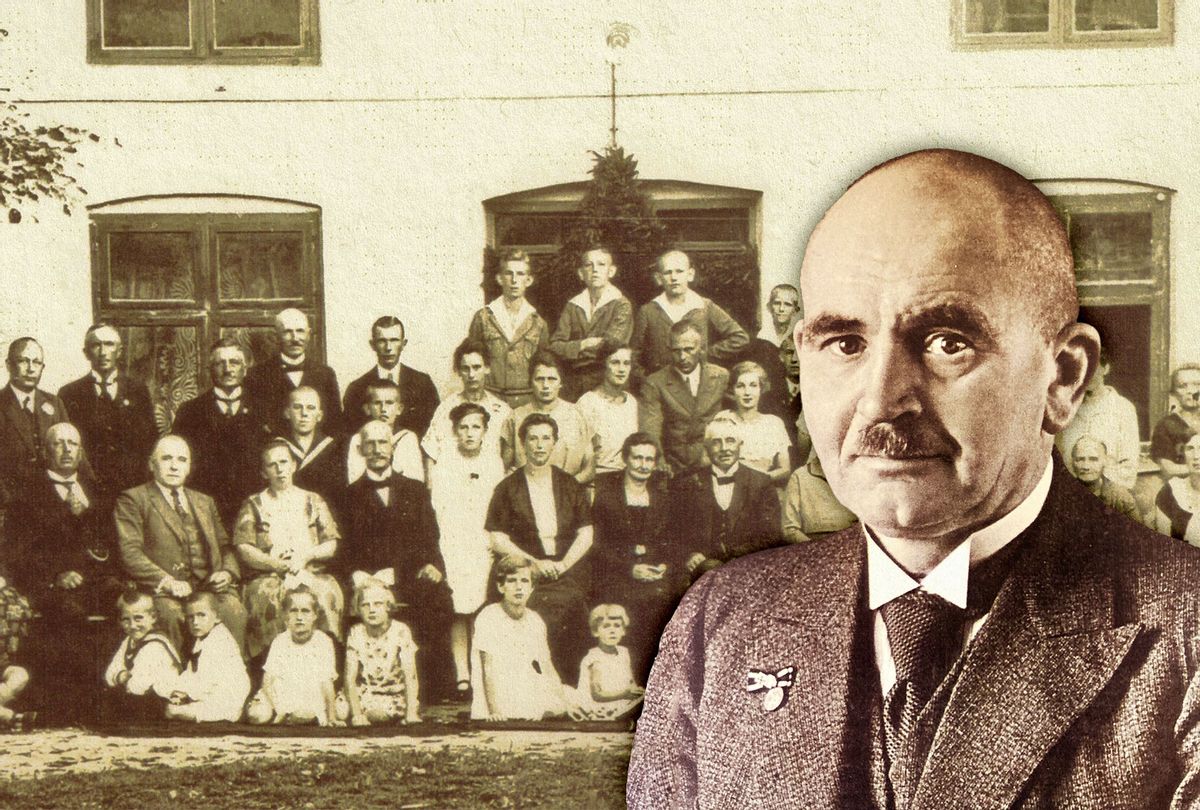

My grandfather was a Nazi. As others, like former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, have also noted, the political events of today remind me of my family's past. My grandfather wasn't among the first to join the party. In fact, it took years to convince him. But Johann Bischoff eventually became a Nazi for the power and safety the party afforded him at the time, and was one of the last to leave when Hitler's forces fell. My family story is one of complicity — of how an educated, pious man became a cog in the machinery of Nazi hatred, only to have it destroy his family and homeland, with my mother and her sisters paying the most for their father's sins. Conservatives who think right-wing extremism in America is not a serious threat to them as well as to their political opponents should take heed of my family's story.

Last week, only ten Republicans in Congress saw fit to impeach a president accused of inciting a deadly insurrection at the United States Capitol. Images of the riot showed chaos, but there is also evidence of coordinated attacks on American democracy. Federal and local law enforcement are warning similar events are planned throughout the country.In a dangerous echo of Nazism, a mixture of prejudice, grievance and ambition fuels this vicious power grab. President Trump's whipped-up minions carry out the physical violence, while Republicans amplifying and acting on the election fraud lie provide a more philosophical assault on democracy.

Across America today, thousands of Republican elected officials — and untold millions of rank-and-file members — are making choices that remind me of the early, incremental choices my grandfather made. Maybe they supported President Trump out of fear for their political futures and safety for their families, or maybe they liked his tax cuts and Supreme Court justice appointments. The end of democracy was far from their minds. They don't believe terrors on the scale of Nazi Germany could happen again, or maybe they believe their privilege protects them.

They don't understand what the combination of hatred and authoritarianism, once unleashed, can destroy. My family is among those who do.

On January 22, 1945, as the Soviet army neared their estate outside of Guttstadt, East Prussia, my German family prepared to flee. Like Liesl von Trapp in "The Sound of Music," my mother, Lieselotte Bischoff, was 16 going on 17. But while Captain von Trapp ripped apart a Nazi flag in protest, my grandfather, Johann Bischoff, cowardly buried his Nazi flag on the way out of town. He worried what the Russians might do to his farm if they discovered a Nazi lived there.

My grandfather wasn't part of Adolf Hitler's political base. He was a large landowner and an active local official in the Catholic Zentrum Party until Hitler outlawed all other political parties. In 1937, he was detained and interrogated for publicly questioning why an elderly Jewish grain merchant, Moses Sass, was sweeping the street.

But after six years of Hitler's Reich in 1938, Johann had become the Ortsbauernführer, the area's leader of the Nazi's nationalized agricultural agency, the Reichsnährstand. Its motto was blut und boden — blood and soil. The agency revived German agriculture after the dire depression, and my grandfather benefited from his position. After much pressure, Johann capitulated and joined the party as well.

Perhaps his land, livelihood, and life were at stake, along with the lives of his wife and eight children. Perhaps he was simply a politically shrewd Prussian. Regardless, he stood by as Hitler's plans unfolded. The Jews in Guttstadt had been his business partners, fellow city councilmen, and comrades in arms fighting for the Kaiser. But he sat by and watched as his Nazi Party imprisoned and murdered the same Jewish townspeople he once called friends, including Moses Sass.

The party also soon bestowed tragedy on his family. Starting in 1940, each of his four sons was drafted. Only a few years later, two were dead and another was a prisoner of war in Siberia. The fourth son, my Uncle Karl, served four years in a Panzer unit across three continents until he lost a leg and returned home.

Meanwhile my mother and her three sisters attended mass and Catholic school and also the meetings of the Hitler Youth group for girls. Despite a raging world war, in 1944, my mother was sent to finishing school in Königsberg, until that August when she escaped Britain's fiery bombing of the city under a wet blanket.

The bombing of Königsberg marked the beginning of the end of East Prussia, but Hitler's Reich ordered summary execution for anyone attempting to escape west. The German women, children and old men were to be the last stand against the Red Army. On January 20, 1945, the first Soviet airstrike hit Guttstadt, and two days later, civilians were finally allowed to evacuate. My family joined hundreds of thousands of East Prussians in the chaotic mass exodus that blizzardy January. Rich and poor fled for their lives on foot and in wagons, but in subzero temperatures under Soviet air raids, it was a deadly slog westward.

After four years of German crimes of war and humanity against Russians, when the Soviet army encircled the Germans that spring, vengeance was theirs. My mother was one of the million German women raped by the Russians. As a Wehrmacht veteran, my Uncle Karl was brutally beaten. During the occupation, a typhus epidemic claimed a younger sister, and almost everything my family owned was taken from them.

After the Potsdam Conference, the remaining Germans in East Prussia were expelled and the refugees prohibited from returning. When my family was told to meet at the train station, they were terrified they would be sent to a Siberian workcamp like so many. My Uncle Karl believed it a certain death; he escaped in the tumult of the transports, abandoning his family.

Atop of coal cars, they arrived at a displaced persons camp. They were lucky to have been sent westward, but the conditions were no better. Lying on straw with little food in tight quarters, disease was rampant. The two younger sisters developed tuberculosis and my grandfather, pneumonia. He died January 24, 1946 — one year after he left his farm. Close to starvation, my mother was the only one able in the family to walk to see to his burial. She wore his old coat, the better one of his once bespoke boots, and a wooden clog she had found.

Later in 1946, the four surviving Bischoff women were resettled in West Germany in the British Zone. The following year Karl found them, and in 1950, another lost brother reappeared, skeletal after six years in a Siberian prison. Eventually, the family made new lives for themselves in Germany and America, where my mother became a citizen.

Some hear this story and feel pity for the innocents; others believe my family received their just due. But this story can do more than elicit a judgment of character. It shows that when governments use hatred and authoritarianism as a political tool, it's not only a danger for the targets of the enmity. Victim, perpetrator, enabler, and bystander — are all in peril.

On January 6, with Thin Blue Line and Trump flags waving around him, a Capitol Police officer was beaten with American flags by President Trump's mob. Some in the mob were itching to maim or kill President's Trump's political opponents. When Congress reconvened later that night, a majority of the Republican Representatives nevertheless voted against certifying the results of a free and fair election. Don't say history can't happen today.

Shares