I didn't grow up belonging to a synagogue, but my grandfather, Ludwig Joseph, was a Holocaust survivor. Technically, he didn't grow up entirely Jewish either. He was, according to the Nuremberg Laws, a "Mischling," which was the slur used in Nazi Germany to describe people of mixed Jewish descent. His mother was a Protestant; his father was Jewish. They lived in Germany, a country they loved, and one in which the unimaginable happened and took everything from them. My grandfather's story is one of miracles and resilience, but it's also one of what happens when antisemitism and white supremacy are tolerated and even amplified.

On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden officially became the 46th president of the United States. I teared up on my burnt-orange couch in Oakland watching him say "and at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed." Just two weeks before I, like many Americans, watched a starkly different scene unravel on those same steps. An angry mob full of Donald Trump supporters attacked the Capitol and tried to stop Biden from becoming president. The people who attacked the Capitol, like the guy in a "Camp Auschwitz" hoodie or the men in vests adorned with far-right symbols, didn't want democracy to prevail. They wanted a man who refused to denounce white supremacists, and who approved of how Kim Jong Un treats North Koreans, to prevail.

Historians will surely study the Trump presidency for decades to come. I believe their analyses, refined by the gift of hindsight, will show with more certainty just how close America came to becoming an authoritarian regime. There have been many times throughout the Trump presidency that I paused to reflect on my grandfather's life in Nazi Germany. I wondered if this was how it was in the beginning for him; a time of red flags minimized by complicity and disbelief. Was the breaking point more obvious during the build up of Nazi Germany, or was it more subtle? Ultimately, my grandfather's immediate family didn't leave, and they suffered for it.

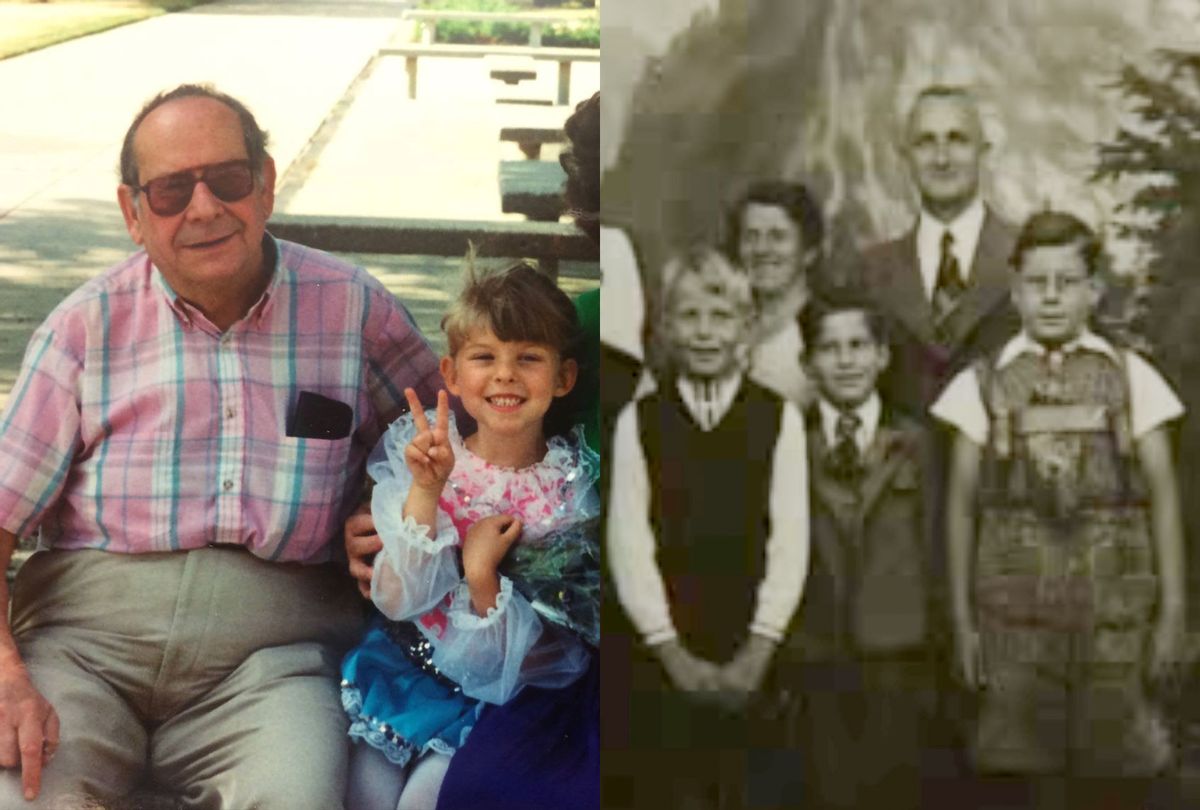

He passed away in 1997, when I was eight years old. Like many Holocaust survivors, he rarely spoke about that time of his life. And even if he did, I was too young at the time to fully comprehend his story. So to find answers, I read an article he wrote and rewatched a three-hour interview he did with the University of Southern California's Shoah Foundation in 1996. Some historical details might be inaccurate, given the nature of trauma and memory, but I did my best to fact check what I could when reconstructing his story. What I learned is that by the time the situation became clearly dangerous for my family, it was too difficult to leave. The state of fear shifted to survival too fast. What kept them from taking action before that point? They just couldn't fathom the state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews could happen to them, in their own country.

* * *

Ludwig Joseph was born to Hertha Sommerfeld and Ernst Dieter Joseph on February 24, 1927. He grew up privileged in the bustling and exciting metropolis of Berlin. His father, Ernst, was an orthopedic surgeon and co-owned his practice with two other Jewish physicians. Hertha was a Protestant. She stayed at home and took care of my grandfather, and a couple years later she had her second son. The family had a governess, private driver, and a vacation home in the mountains, which was later occupied by Nazi officers. Life was good in the beginning, my grandfather said. Even though the Nazi party was slowly gaining power in Germany, nobody at the time could have predicted the horrific events to come.

"There was always an undercurrent of antisemitism; maybe it wasn't an undercurrent, maybe it was more obvious," my grandfather explained. He was too young to truly recognize and understand it, but in 1996, he recalled a story his mother told him about his father and his uncle before World War II officially started. They were on a "pleasure ride," driving around Berlin, some time between 1929 and 1931. Their driver accidentally took a wrong turn on the highway and got lost. They stopped to ask for directions from farmers working nearby, who came over to the window. But a quick look at Ernst and his brother stopped them. "Jews," they said, and walked away. They didn't want to help them because they were Jewish.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler was named chancellor of Germany; Germans who upheld and agreed with these antisemitic acts, like those farmers, officially had a leader to follow. The same year Ernst received an earth-shattering letter from the Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Ärztebund (the Nazi government's medical association) telling him that he could no longer own his practice. This was my family's lifeline, and a major source of pride; his thriving practice wasn't an easy one to give up. It was his entire livelihood. Ernst and Hertha put their heads together to find the best solution for their family — one that could retain some sense of normalcy for their children. They decided to divorce, and hand over the practice to Hertha. Technically, since she was Protestant and then registered as an "Aryan," she could run the practice, but she couldn't be married to a Jewish man. She also had to co-own it with a Nazi official. My great-grandparents lived apart to make it look like they were really divorced, and went through with the paperwork, but their love was far from over.

Of course, this terrified Hertha. At this point she wanted to leave Germany. Her brother, a pacifist and writer, warned them to leave too. My grandfather said he remembered his mother saying she was afraid. "A government that has authority that is capable of making them divorce because they were Jewish, what would be their next step?" he said. "This was all leading up to a very frightening course of events." But his father wasn't scared. According to a story that his mother told him, they were listening to one of Hitler's "ramblings" on the radio one night. "Ernst would say 'That man is an idiot, 'That's impossible' [or] 'He's kidding,'" Hertha told my grandfather. Arno, Hertha's brother, looked at Ernst and told him to leave. Take your family, transfer all your money and go to Switzerland, he said. "But my father did not believe that this could happen."

My grandfather estimated that a year after Ernst got his license taken away from him, it was reinstated with segregationist stipulations. He had to wear a Jewish badge on his doctor's coat and could only treat Jewish patients. But Ernst's brother suffered too much from the degradation and humiliation already. He became despondent, my grandfather said, and engulfed in so much despair that he took his own life. His wife and children moved to Switzerland. A couple years later, in 1937, Ernst died from natural causes. "He died not knowing what terrible things would happen had he lived," my grandfather said, almost grateful that he didn't.

In 1938, my grandfather went to the German equivalent of high school. At this time, he was still allowed to legally attend school, but all students had to register whether they were Jewish, Aryan or half-Jewish. In the early years of the Nazi regime, he hadn't faced much antisemitism from other kids, he said, but that changed as he got older and with the rise of Hitler's Youth group, which became compulsory in 1936.

In 1942, another Nazi regulation stated that anyone who was half-Jewish could no longer attend high school, or any school. My grandfather remembered this day, and when the principal called him down to the office to deliver the news. "How could you choose a profession for the rest of your life?" he asked the principal, wondering what his future held at 15. "You can't," the principal told him. My grandfather noted that he felt the principal "honestly regretted" having to tell him that news. In some ways, my grandfather believed that it was for the best, as school had become increasingly unpleasant for him. "I wanted to learn and benefit as much as I could from an education, but it was almost made impossible," he said. On Wednesdays, all the members of the Hitler Youth group would wear their brown shorts and swastikas to school, and on these days, his classmates felt especially emboldened to discriminate. "My English teacher asked me to read my homework and they would say 'Shut up Jew, sit down'," he recalled. "'We don't want to hear you." His English teacher did nothing to stop it.

His mother tried to find different schools that would take him. A Jesuit school almost did, but ultimately refused because they were scared of potential consequences. His mother hired a private teacher to teach him shorthand and typing in secret. In the winter months, he had to sneak into this teacher's apartment; it was his last grasp to continue his education. "This man took a very strong risk, I don't remember his name, but I will always be grateful for him," he remembered. At the same time, he held a fake job at an insurance company, to make it look like he was working, because all Germans had to work. His employer was a friend of his uncle's, and he was trying to build another kind of insurance. "So he could say 'I helped someone,'" my grandfather said. "A lot of people tried to build this kind of insurance for themselves."

By this time, his mother wanted to flee Germany, but now it was too late. The consequences of getting caught outweighed, they believed, the consequences of staying. They knew the precariousness of their situation. "I knew that our situation was pretty bad, almost hopeless, and everyday that we survived that was another day gained in our lives," he said. In 1944, he received a letter requiring him to report to Berlin's Steglitzer railroad terminal which would take him to the "Zwangsarbeitslager," a forced-labor camp called Lager Zerbst. The farewell was a tearful one, as his mother, uncle and aunt tried to "look brave" on a cold November day. They didn't know if they'd see each other again.

My grandfather ended up at a labor camp 200 miles southwest of Berlin that was part of a military base for a fighter squadron of the Luftwaffe. For the next six months, he worked seven days a week from 7 a.m to 6 p.m., and slept on a makeshift straw mattress on the floor in a barrack with 10 other men on bunk beds. Unlike in other concentration camps, he wasn't tattooed or made to wear a striped uniform. But he was told most days that if he didn't want to do the work — pouring concrete, schlepping massive machinery, and laying bricks — that he would go to a place "worse than this."

At the time, not much was known about what was happening at concentration camps like Auschwitz or Dachau. There were "whispers," he said, and they had an idea that they were "pretty sinister." But the horrors of the Holocaust weren't entirely realized until the Allies liberated camps across the Nazi-occupied Europe in 1945. The SS guard who visited weekly didn't fail to provide hints to my grandfather and his fellow prisoners, though. "Your work is not buying you time to stay alive, because all Germans classified as half Jews will be killed soon under the final solution of the Jewish question under the Nuremberg Laws," he'd say. This resulted in an unspoken "passive resistance" among prisoners, including my grandfather and those he referred to as his comrades. "People appeared to either be acting dumb or clumsy, but there was a very orchestrated effort to undermine the building of that airfield," he said. It was in the name of survival, especially as some men became sick and died from lack of medical attention.

On April 14, 1945, artillery fires brightened the sky. That same day during morning roll call, they were told that they were going to be moved to a new camp in Bavaria, the only part of Germany still unoccupied by Allied troops. But around noon, U.S. bombers started an air raid on the camp and all bets were off. The guards of the camp got distracted trying to salvage furniture and their homes, which is when he noticed many of his comrades disappearing into a nearby forest. Crawling through the high weeds between the camp and the forest, he ran for his life once he and a friend reached the forest. The SS guards from the camp eventually caught on to what was happening and rode their motorcycles into the forest and tried to recapture them. An unexpected sneeze or a cough could have cost him his life as he hid in a furrow under thick brush. Once they heard the motorcycles leave, they walked four miles to a nearby town called Lindau. As they emerged from the forest, they were greeted by a farmer couple. At first, he worried they'd turn him in, but right away they gave him a plain coat and wished him well, congratulating him on his freedom.

For the next six months, he lived underground with a friend in Berlin until the Russians captured the city. Then, together, they hitchhiked to Munich, where he reunited with his family. After the war, he worked as a reporter for Die Neue Zeitung, a German daily newspaper published by the U.S. Army in 1945. In 1951, he emigrated to the United States. Germany never felt the same for him.

The Holocaust as we remember it today, the concentration camps and mass murder of six million Jews, didn't happen overnight. It was the culmination of antisemitism tolerated by the public, emboldened by racist laws and an authoritarian leader, which turned into state-sanctioned violence, and eventually what Nazi leaders called "the Final Solution" over the course of nearly two decades. Hitler had promised that once he was in power, his foremost task would be the "annihilation of the Jews." Historians don't know exactly when he decided to murder European Jews in gas chambers; some suspect it was around 1941— eight years after my great-grandfather was told he couldn't own his medical practice anymore because he was Jewish, and nearly ten years after a farmer refused to give his driver directions because he was Jewish.

* * *

My grandfather visited Germany often to see family after he moved to the United States, but admitted he had uneasy feelings when he did. "I can't forget these times — the fear, the persecution and the humiliation," he said in 1996. "And a lot of times when I'm traveling to see my brother in Germany I feel that the people I see of my generation, I wonder 'What were they doing between 1933 and 1945?'"

In 1996, when my grandfather was interviewed by the USC Shoah Foundation, his final statement warned that the we must never let Holocaust denial go unchallenged.

"We would do a great injustice to all those millions of people, our brothers and sisters who were murdered in the concentration camps," he said. "We must continue to go on, maybe some of us can forgive, but nobody can ever forget what happened to us."

In 2014, a survey estimated that only 54 percent of the world's population has heard of the Holocaust. It's troubling to think about those who don't believe the Holocaust happened, or who believe that the details of it have been overhyped, or are unaware of the depth of cruelty that happened less than 100 years ago. Not only does this do a great disservice to the memory of Holocaust survivors, like my grandfather said, but it also furthers the belief that such an atrocity could not repeat itself today. Democracy may have prevailed in this moment in American history, but that doesn't mean we can stop fighting the forces of white supremacy and hate. There's too much at stake.

Shares