Writer/director Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr. makes a distinctive feature debut with "Wild Indian," a drama premiering at the Sundance Film Festival. The film opens with the text, "Some time ago . . . There was an Ojibwe man, Who got a little sick and wandered West." After a brief episode featuring an Indigenous man, the story jumps to the 1980s. Mawka (Phoenix Wilson) and his cousin Ted-O (Julian Gopal) are teens in Wisconsin. Mawka has abusive parents and hangs out with Ted-O, because he cannot bear being at home. One day, an incident changes the boys' lives forever.

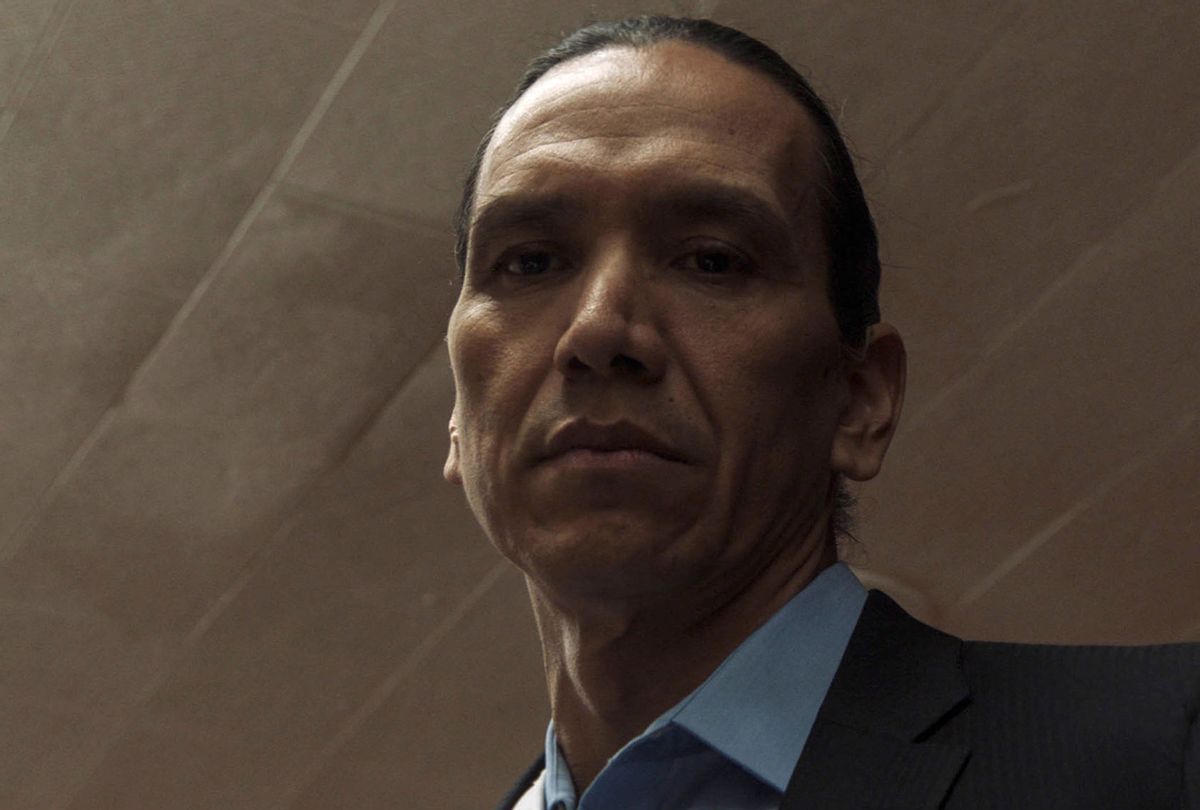

"Wild Indian" then skips ahead to 2019, and California, where Mawka, now anglicized to Michael (Michael Greyeyes), is a successful businessman with a white wife, Greta (Kate Bosworth), and a new baby. Meanwhile, Ted-O (Chaske Spencer of "Winter in the Blood") is seen being released from prison. He heads to his sister Cammy's (Lisa Cromarty) and finds work as a dishwasher. However, Michael and Ted-O's past crime and shared trauma brings the men back into each other's lives with volatile results.

Corbine, who has an Indigenous background, displays a restraint in his storytelling that is hypnotic. The filmmaker spoke with Salon about his debut, which features a chilling performance from Greyeyes as a man whose actions empower him and a heartfelt turn from Spencer as a man who cannot escape his past.

The Indigenous filmmaking community is starting to grow. Can you talk about your background and how you got into cinema?

Chris Eyre the director of "Smoke Signals" reached out and requested the link — I've known him a couple years — and he was positive about the film. I grew up being a huge fan of film. I wanted to be a writer. I kind of pretended that I didn't want to be a filmmaker for a while, because that's not as legit as being a novel writer. I got involved in the film club [at school] and writing scripts, and that's how I got into directing and writing films which was about 10 years ago. I steadily over the years kept making short films, everything from the hokiest genre to sensitive arthouse love story type films. But I found my voice when I started exploring Native themes. I grew up on reservations. Both my parents are Native and grew up on the reservation as well. It was so ingrained in me, but I didn't want to exploit stories for filmmaking. But when I started writing about it, it became a really personal journey for me, to explore stories using the form of film, which I knew so well. The first short I made about my Native background ("Shinaab") played Sundance, so I knew there was something there.

"Wild Indian" opens with an Indigenous man who "got a little sick and wandered West." This is obviously a parallel for Mawka/Michael. Can you discuss this myth and its implications?

The genesis of that was not necessarily an Ojibwe myth. When settlers came, Ojibwe people would get sick and they didn't want to infect anyone else, so they wandered upriver. If they got better, then would come back, but a lot of times they didn't come back. They'd disappear upriver. That was specific to stories I heard from my tribe, which is Ojibwe. I was taking that and made it a parallel to what Mawka was doing.

There is a line early in the film as Mawka is in school, listening to a priest talk about tortured spirits, and the nature of humans is to suffer. How did that idea inspire you/"Wild Indian?"

It's interesting that the character connects with Christian religion.

We find Ojibwe culture is very much about storytelling and taking applicable themes from those stories and having it inform the way you look at the life around you. He replaced that mode of self-discovery and the freedom of being someone Ojibwe and incorporated that meaning-seeking into the Christian religion and he found meaning there.

The boys' crime in the film is depicted in an almost matter of fact way; it's not sensationalized, which makes it perhaps more horrific. Can you talk about your thoughts on this incident and the decisions you made in terms of depicting it?

I knew it was a really disturbing thing to watch. I didn't want to linger on it too long. I just wanted it to inform who this character was and the lengths he will go to find a sense of power. Expressing it that way, and not lingering too much on them or the horror on it, doesn't make it extra disturbing for the audience. But maybe by doing it that way that I did, maybe it is more horrific.

Michael also has a real power, especially when he encounters a stripper or meets a woman he visits in a hospital. Michael Greyeyes give a great performance because you feel this tension every time he is in a room. Can you talk about his creating his menacing disposition?

It started with the idea of trauma. Traumatized people tend to perpetuate trauma in people's lives. He is somebody who will get what he thinks he needs or wants at all costs. His morality is relative. I don't necessarily think he's a bad man, but I think when he is pushed, he makes decisions that are morally dubious, I suppose.

When the story jumps to 2019, you show Mawka anglicized and renamed Michael, who asks his coworker (Jesse Eisenberg) about the length of his braid. How did you conceive of his adult character?

Michael has become someone free of an identity only in so far that he can use that identity to serve getting what he wants, which is a leg up, a need or want for representation in modern corporate America to further his own career. He's leaning into it by growing his hair long and braiding it and being a symbol of Native Americanness. He's got the perfect profile, and that's what he's riding on.

In contrast, Ted-O is more thoughtful. He makes bad choices, has regrets, such as his facial tattoo. He seeks forgiveness. He is haunted. What can you say about his character as a foil for Mawka/Michael?

Ted-O is human. He's the heart of the film, and it was always designed that way. He doesn't represent anything innately Ojibwe Native. What he does represent is the way that you feel the film and understand the emotions of the character. You can latch on to him. Chaske drew that out and elongated it.

Let's talk about the performances.

Trying to find the performance of Michael's character, or older Mawka, was tougher because he's so nuanced. He is very much in between the things that he says. He never says anything really about the things that are going on. It's all about the subtext and trying to figure out ways to stage what he's going through emotionally, but also trying to find the interesting little ways to iron out the arc of each scene. Michael is such a great performer that we figured out a way to get those scenes down.

Chaske, I've been writing this for him for years. I was thinking of him constantly when writing the character. He had a sense of pathos that is hard to come by. I reached out to him and he was really excited for it, and I barely had to give him any direction. He came in and just knew and understood what I was going for.

"Wild Indian" includes a speech where Michael asserts that Natives are all "liars and narcissists, descendants of cowards; the worthwhile ones died fighting." Can you talk about his self-hatred and self-loathing in the Indigenous community? He assimilated into American culture, marrying a white woman, having a corporate job . . .

I don't necessarily think it's a condemnation of Native people, it's more this guy is sick and having that tirade of Natives being that way is a conflation of his own personal failing and the greater failing of Makwa. It resonates because you can see it in his perspective. Like I said, trauma perpetuates trauma. He conflated the trauma he had as a kid, with his parents, and being from an entire people and that wasn't the case.

Can we talk about his parents and the depiction of the abuse of Mawka?

He's treated like he's a resentment, and that would traumatize any kid. Every kid wants to be respected and wanted, and he's not wanted anywhere. He's not wanted at home or at school either; he's bullied. I think he wants a sense of self and a way to get that sense of self is to act on what he thinks might make him feel more powerful. I didn't want to linger on the abuse too long. It's not anything specific to Ojibwe or Native people. There are a lot of people who grew up in that way.

What can you say about the film's themes of repression?

I think people in my community — and that goes for myself too — we're not super vocal or verbal about our feelings. We keep them close to the heart. It's not a vulnerability we, or I, want to have out in the world. That's something I noticed in my family; I can't speak for all Ojibwe people. I had to figure out a way to tell a story in a film that explored about us talking about everything but the thing that's bothering us. That is repression. It was a cultural thing, but it also became a narrative tool.

Shares