"Well, ain' dat somethin'. De Jew, he wanna buy de bess playuh we done got! And how much you wanna pay, Jew?"

— Philip Roth, "The Great American Novel"

In the U.S. census I am, for good or bad, counted as Caucasian.

— Philip Roth, "The Counterlife"

The main rot in the minds of "academic" liberals like yourself, is that you take your own distortion of the world to be somehow more profound than the cracker's.

— LeRoi Jones, "Reply to Philip Roth"

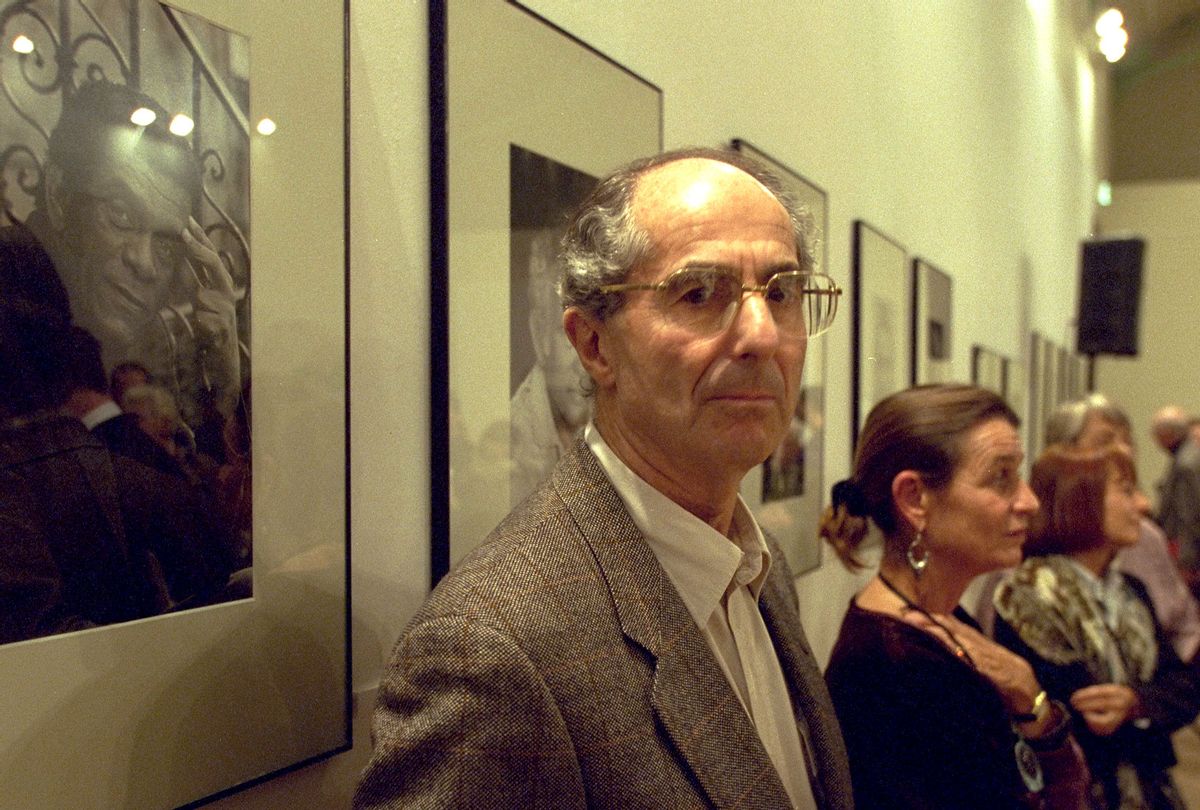

Fans and scholars alike tend to believe that Philip Roth wrote sporadically and sympathetically, though perhaps not entirely unproblematically, about Black people. The assumption is based on two well-known works. The first is the 1959 novella "Goodbye, Columbus." Its Jewish protagonist, Neil Klugman, behaves protectively toward an African American kid who marvels at post-Impressionist paintings in the Newark Public Library. Neil shows a lot of concern for "the small colored boy"; he even dreams about him.

Then there's "The Human Stain" (2000), whose plot revolves around a Black, non-Jewish scholar who passes as a white Jew. While not without its critics, this novel won the PEN/Faulkner Award. Like "Goodbye, Columbus," it is often lauded for its thoughtful engagement with America's racial dilemmas.

On the basis of those two texts, one might surmise that Roth was yet another Jewish liberal, doing his small part to extend the hand of friendship to another oppressed minority. If so, the author would be following in the footsteps of many 20th-century Jewish intellectuals, artists, and activists who made common cause with African Americans. This partnership between Blacks and Jews, often called the "Grand Alliance" or "Grand Coalition," "is the stuff of legend, as it were. In recent years scholars have questioned how stable and robust this partnership actually was. In any case, the idea that Roth depicted African Americans sporadically, thoughtfully, and sympathetically is widespread. I will refer to this way of thinking as the "Alliance Paradigm."

Yet a study of Roth's entire fictional corpus reveals a much more complicated state of affairs. For starters, Roth did not write sporadically, but consistently, about African Americans. To help the reader grasp how consistently Roth engaged this subject in his fiction, I have tried to take stock of every available proof text. References to Black people or Black issues are present in 26 of his 28 book-length works of fiction. No fewer than 10 of his short stories touch upon the theme as well.

If a researcher were to scrutinize all of these texts, it would become evident that Roth's representation of African American characters can be neither sympathetic nor thoughtful. From "The Box of Truths" (1952), until his finale, "Nemesis" (2010), we encounter: (1) a steady flow of minor characters who are Black, (2) disparaging comments about the Blacks of Newark, (3) racist banter uttered by white gentiles, (4) racist banter uttered by white Jews, (5) caricatures of Black English, (6) asides on the physiognomy of Black bodies, especially those of women, and, (7) occasional references to prominent African Americans.

What we are about to see is surprising. Roth's sketches of African American (and African) characters are not infrequently racist. This reeks of a double standard; he railed against anti-Semitism in the very same stories in which he indulged in racist depictions. What is also surprising is that the patterns, and even some texts to which I'll draw your attention, remain almost completely unremarked upon. This component of his writing has seldom been flagged by Roth scholars and critics.

These considerations will prompt me to suggest that we abandon the Alliance Paradigm. Roth's African American portraiture, I will argue, makes better sense when contextualized within the complex, shifting relationship between Blacks and Jews in the United States. Roth's fiction often reflected the antagonisms between these two supposed "allies," albeit in a one-sided manner. What emerged were numerous representations of Blacks that are thoughtless and occasionally quite disturbing.

Fellas

As just noted, Roth's representation of an African American boy in "Goodbye, Columbus" has generally been interpreted as well-meaning. He depicts a youth who has the precocity to hang around a library all day, peruse Gauguin's paintings, and drop F-bombs. That's one likable kid!

In the same narrative, our Jewish protagonist, Neil Klugman, is often symbolically twinned with the boy. The scholar Elèna Mortara has pointed out that when "Goodbye, Columbus" first appeared in the New Yorker in 1959, the accompanying illustration was of an African American child. As far as liberalism back then went (or could go), this was the type of story that challenged American racism.

Roth may have issued the same noble challenge in "Defender of the Faith" (1959). The story is narrated by Nathan Marx, a Jewish drill sergeant. He is frustrated by a trainee of dubious sincerity who plays the Jewish Card in order to gain religious accommodations. When Marx confers with a certain Captain Barrett about the matter, his white gentile superior expounds as follows: "Marx, I'd fight side by side with a nigger if the fella proved to me he was a man." A few sentences later Captain Barrett asks, "You're a Jewish fella, am I right, Marx?" Two "fellas" — one Black and one Jewish. These fellas are coupled in Captain Barrett's thoughts, likely because our author wants to spotlight a broader linkage in the white Christian mind-set.

The same linkage is seen in "Letting Go." A working-class white woman by the name of Theresa Haug recounts a story about a boy who is hit by a car and taken to "the Jewish hospital." "They made a Jew out of him," she observes, implying that he was forcibly circumcised. After giggling she adds, "He was a nigger, so must be." Later in the work, the woman with the un-kosher surname chuckles again as she wonders "what it was like to do it with a Jew." While contemplating that erotic possibility, "she remembered the story of the little nigger boy they had taken to the hospital back home."

That white Christians are wont to connect these two minority groups is a grim American truth Roth is eager to expose. In "I Married a Communist," we learn that when Ira Ringold was in the armed forces, "someone in the mess hall called him a Jew bastard. A nigger-loving Jew bastard." Ira reveals that the culprit was "a southern hillbilly with a big mouth."

White gentiles in Roth's works don't always speak about Blacks and Jews; sometimes they reflect solely on Blacks. In "When She Was Good" (1967), two families, the Bassarts and Sowerbys, are discussing the pros and cons of living in Chicago. Lloyd Bassart exclaims, "They've got a big colored problem down there, and I don't envy them." To which his nephew Roy responds: "It isn't Negroes, Uncle Lloyd. You people think everything is Negroes — and how many Negroes do you actually know? Really know, to talk to? . . . I knew one who I used to talk to a lot. . . . He was a darn smart guy too. I had a lot of respect for him." Roy's cousin Ellie Sowerby chimes in: "I know a girl who dates a Negro. . . . She's probably a red." The assembled white folks then debate the possibility of befriending Blacks (some in favor), and dating Blacks (less enthusiasm for that).

Which brings us to "The Great American Novel." The entire tale is recounted by Word A. Smith, an octogenarian baseball writer who traffics in odious stereotypes. He introduces us to a train conductor named George who, while "scratchin' his woolly head," comments, "Well, suh, day don' say nuttin' 'bout dat in de schedule." A few pages later Ernest Hemingway enters the storyworld and describes Melville's "Moby Dick" as follows: "Five hundred pages of blubber, one hundred pages of madman, and about twenty pages on how good niggers are with the harpoon."

Elsewhere, Smith (and Roth) return to literary minstrelsy. We are told that Aunt Jemima, of flapjacks fame, is a cunning businesswoman who owns an entire Negro baseball league. One might expect that an accomplished entrepreneur like her wouldn't speak like this: "howdydo, Reverend! Ain't we honored, though!" In Smith's other reminiscences, racial slurs drop freely from the mouths of white baseball players who speak of "coons" and "spades."

About 300 leaden pages into "The Great American Novel," Smith recounts a tale featuring the long-serving manager of a feckless baseball team known as the Ruppert Mundys. Ulysses S. Fairsmith is a fervent Christian, scarred by the memory of having tried to bring the gospel to Africa twenty years prior. Clad in his "khaki short pants, half-sleeved shirt, and pith helmet," he dreamed of Christianizing the indigenes by introducing them to the delights of baseball. Roth goes all in here, devoting some 16 pages to recounting a religious mission gone terribly wrong. The section is deeply offensive, often to the point of unreadability. The account includes references to "the primitive interior of Africa," "savage women" and "black devils."

Upset about a rule preventing them from sliding into first base, the mercurial tribesmen revolt against Fairsmith. The missionary and his nephew are readied to be slaughtered and eaten by the men whom they tutored in America's pastime. During the ensuing cannibalistic ceremony, Roth describes the ritualistic "deflowering" of virgins with baseball bats.

One would have to deploy considerable ingenuity to read these asides as anything other than gratuitous racist jokes. What rankles about these descriptions is the obvious delight the author seems to have taken in creating them. As he told Joyce Carol Oates about the vibe he adapted while working on "The Great American Novel": "I tried to put my faith in the fun I was having. Writing as pleasure."

A final example of how Roth's white gentiles talk about Blacks can be found in the autofictional novel "Deception." The work is comprised of chapter-length "fragments of conversation" between "Philip" and others. One exchange is with a Czech writer named Ivan. He is convinced that his wife, Olina, is having an affair with Andrew, a Black neighbor. There is almost no racial stereotype that Ivan doesn't deploy: "It's that nigger that does it. I don't say 'black person' I say 'nigger.' . . . [H]e gives her an orgasm on his black prick. . . . He's a typical pimp type. . . . Doesn't know how to spell, writes like a child. This half-illiterate black guy. . . . Black guy doesn't work. Lives off her unemployment benefits. . . . I couldn't kiss ever again that mouth that sucked that long black prick." Unhinged Ivan soon casts aspersions on "Philip's" talent as a writer and accuses him of also having slept with his wife. "Philip" responds to Ivan by (1) denying that he is having an affair with Olina, and (2) taking offense at Ivan's criticism of his writing ("So, my books stink too"). "Philip" does not raise any concerns about Ivan's racist diatribe. A few pages later, "Philip" rants about an anti-Semitic incident he endured in London.

Cracks/Malignancies

We just encountered a slew of white Christians who served up some choice racial invective. Our interest now shifts to how Roth's Jewish characters engage with Blacks.

Ira Ringold in "I Married a Communist" is nothing like any of the white gentiles we just encountered, nor like any of the Jews we shall meet below. His Communist convictions motivate him to actually seek out working-class Black people. Young Nathan Zuckerman accompanies Ira to Newark's Black Third Ward and observes, "I'd never before imagined, let alone seen, a white person being so easygoing and at home with Negroes." I have a question, though: If Nathan Zuckerman is recounting this story a little before the year 2000, why does he continually refer to Blacks as "Negroes"?

In any case, Ira engages in street-corner political banter with a group of Black men. While his exchanges with them reveal him to be confident of his Communist platitudes, he is ultimately respectful. Elsewhere, he displays the well-known condescension of the know-it-all comrade. This is evident as he harangues Wondrous, the cleaning woman who works in his wife's Greenwich Village townhouse. Ira scolds her: "I don't know how a Negro woman can get it into her head that the Democratic Party is going to stop breaking its promises to the Negro race." He gets so mad that he threatens to throw a dish. To which Wondrous responds: "Do what you want, Mr. Ringold. Ain't my dish."

Yet, as far as Roth's depictions of Jews speaking with, and reflecting on, Blacks, Ira is the least offensive of them all. In the 1962 "Letting Go," our secular Jewish narrator, Gabe Wallach, introduces us to an acquaintance named Blair Stott. Of this man, Wallach says that he wore two masks: "Alabama Nigger and Uppity Nigger." The description comes absolutely out of nowhere. It's hard to tell why Gabe Wallach (or Roth) has taken the time to drop a slur like this into his narrative, unless Gabe wants to confess his racial hang-ups to us. Such a confession, however, would seem to have no connection to the story line.

Blair speaks what Roth imagines Black English sounds like. Thus, he uncorks sentences like this: "we is all of us taking a deserved rest, for we expended a prodigious, a fantastic, a burdensomely amount of laboriousness and energy." African American characters often talk this way in Roth novels. "Who you supposed to be?" snarls a Black drug dealer in "Zuckerman Unbound." In "The Anatomy Lesson," we meet a cleaning woman, Olivia, described as "a small, bottom-heavy, earthbound stranger, the color of bittersweet chocolate." Surprised to see Nathan Zuckerman in her place of work, Olivia exclaims: "Who you!' . . . My God, you like t' scared me to death. My heart just flutterin'. You say you Nathan? . . . Well, you a good-lookin' man, ain't you?"

The convoluted ways Blacks figure in the Jewish mind is insightfully explored in "Portnoy's Complaint." During his therapy, Alexander Portnoy reveals that he had Communist sympathies in his adolescence. As an eighth-grader he was lauded for his "courageous stand against bigotry and hatred." The middle-schooler led a protest when African American singer Marian Anderson was not permitted to perform in Convention Hall. As an adult, Alexander works as the "Assistant Commissioner for the City of New York Commission on Human Opportunity" in the mayor's office, where he defends the civil rights of indigent minorities.

Liberal Alex inveighs against his parents' racism. He excoriates his mother's insincere and patronizing attitude to Dorothy, the African American maid. As for his father, an insurance salesman, he offers this description:

He lurks about where the husbands sit out in the sunshine, trying to extract a few thin dimes from them before they have drunk themselves senseless on their bottles of "Morgan Davis" wine; he emerges from alleyways like a shot to catch between home and church the pious cleaning ladies, who are off in other people's houses during the daylight hours of the week, and in hiding from him on weekday nights. "Uh-oh," someone cries, "Mr Insurance Man here!" and even the children run for cover—the children, he says in disgust, so tell me, what hope is there for these niggers' ever improving their lot?

The coarseness of his father incenses Alex: "And I tell you, if he ever uses the word nigger in my presence again, I will drive a real dagger into his fucking bigoted heart!"

It's ironic that at the very moment Portnoy is decrying irrational hatred for others he is indulging in it as well. His 274-page oration reveals an individual teeming with resentment toward Poles, Irishmen, Puerto Ricans, Chinese, Italians, gays, women, all gentiles and, of course, Blacks. Such sentiments, needless to say, are surprising coming from liberal Alex. Norman Podhoretz, in a controversial essay, once confessed that "we white Americans are . . . so twisted and sick in our feelings about Negroes." Via Alex, Roth demonstrates the contradictions of racial liberalism; he manages to draw our attention to a real crack and malignancy in the Jewish American psyche.

More evidence of how some Jews really feel about Blacks surfaces in a short piece entitled "On the Air." John Updike, Roth proudly recalls, once described it as "a truly disgusting story." The narrative, such as it is, centers on one M. Lippman, a Jewish talent agent, intent on convincing Albert Einstein to host a radio show. "Mostly I represent colored," Lippman informs Einstein in a meandering letter. He references two tap dancers he works with ("Buck and Wing"). Lippman boasts that he is helping these young men "to raise themselves into a respectable life."

Then we hear Lippman's inner thoughts: "Who were Buck and Wing when he found them? . . . They were two dumb nigger kids giving ten-cent shines outside his shoe store." Later on Lippman muses: "All he had set out to do was to take two little jigaboos who could already tap-dance better than they could walk, and teach them to do it without saying 'shee-yit' every word. And to get the lice off them." By the time we learn that Lippman taught them "to eat a piece of watermelon with a knife and a fork," the story has vindicated Updike's verdict.

The fictional Jews in these Roth tales are every bit as bigoted toward African Americans as their white gentile counterparts. The question is, why?

Shares